Understanding a company’s financial health is crucial for investors, creditors, and management alike. Financial statement analysis provides the tools to dissect a company’s performance, revealing its strengths, weaknesses, and potential risks. By examining key financial statements—the balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement—we can gain valuable insights into a company’s liquidity, profitability, and solvency. This analysis goes beyond simply looking at numbers; it involves interpreting trends, identifying patterns, and making informed judgments about a company’s future prospects.

This guide will equip you with the knowledge and techniques to effectively analyze financial statements, enabling you to make sound financial decisions. We will explore various ratio analysis techniques, delve into the specifics of each financial statement, and examine the importance of trend analysis and forecasting. We will also address the limitations of relying solely on financial statements and the need to consider qualitative factors.

Introduction to Financial Statement Examination

Financial statement examination is the process of reviewing and analyzing a company’s financial statements to understand its financial performance, position, and cash flows. This involves scrutinizing the information presented to assess its accuracy, completeness, and compliance with accounting standards. A thorough examination goes beyond simply reading the numbers; it requires critical thinking and the application of analytical techniques to draw meaningful conclusions.

Understanding financial statements is crucial for a variety of stakeholders, including investors, creditors, management, and regulators. Investors use this information to make informed decisions about investing in a company, while creditors assess creditworthiness and risk. Management uses financial statement analysis for internal planning and control, identifying areas for improvement and strategic decision-making. Regulators utilize this information to ensure compliance with accounting regulations and to monitor the financial health of businesses within their jurisdiction.

Types of Financial Statements

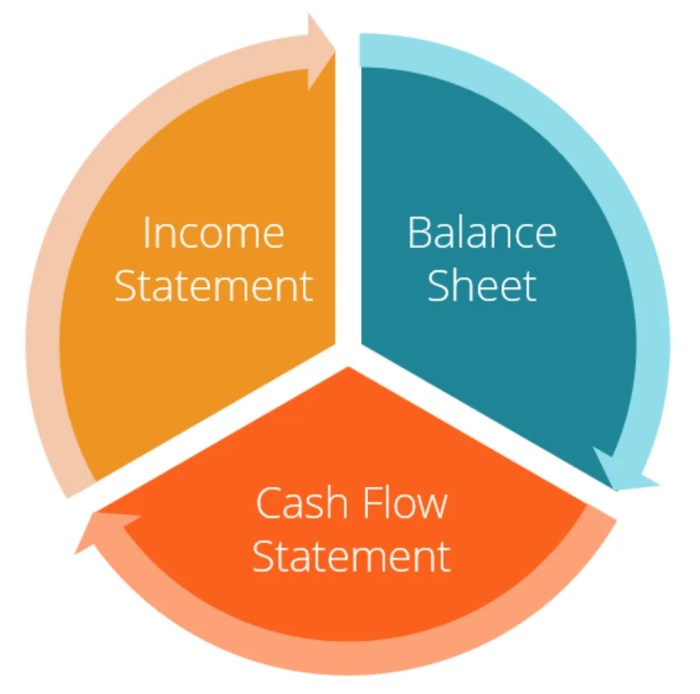

Financial statements provide a comprehensive overview of a company’s financial health. Three primary statements are essential for a complete analysis: the balance sheet, the income statement, and the cash flow statement. Each statement offers a unique perspective, and together they paint a holistic picture.

Balance Sheet, Income Statement, and Cash Flow Statement Comparison

The following table compares the three main financial statements, highlighting their key differences and uses:

| Statement | Purpose | Time Period | Key Elements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Balance Sheet | Shows a company’s financial position at a specific point in time. | Specific date (e.g., December 31, 2023) | Assets, Liabilities, Equity (Assets = Liabilities + Equity) |

| Income Statement | Reports a company’s financial performance over a period of time. | Period (e.g., fiscal year, quarter) | Revenues, Expenses, Net Income (Net Income = Revenues – Expenses) |

| Cash Flow Statement | Tracks the movement of cash both into and out of a company over a period of time. | Period (e.g., fiscal year, quarter) | Operating Activities, Investing Activities, Financing Activities |

Ratio Analysis Techniques

Ratio analysis is a crucial tool in financial statement examination, providing a quantitative assessment of a company’s performance, liquidity, and solvency. By comparing different line items within the financial statements, ratios offer insights that individual figures alone cannot. These insights allow analysts to understand a company’s financial health, identify trends, and make informed decisions regarding investment, lending, or operational improvements.

Key Financial Ratios and Calculations

Several key financial ratios offer valuable perspectives on a company’s financial standing. We will explore five essential ratios, demonstrating their calculation and interpretation using hypothetical data.

| Ratio | Formula | Calculation (Hypothetical Data) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Ratio | Current Assets / Current Liabilities | ($50,000 / $30,000) = 1.67 | Indicates the company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations. A ratio above 1 suggests sufficient liquidity. |

| Quick Ratio | (Current Assets – Inventory) / Current Liabilities | ($50,000 – $15,000) / $30,000 = 1.17 | A more conservative measure of liquidity, excluding less liquid inventory. |

| Profit Margin | Net Income / Revenue | ($5,000 / $100,000) = 0.05 or 5% | Shows the percentage of revenue remaining as profit after all expenses. A higher margin indicates greater efficiency. |

| Debt-to-Equity Ratio | Total Debt / Total Equity | ($40,000 / $60,000) = 0.67 | Measures the proportion of financing from debt compared to equity. A higher ratio indicates higher financial risk. |

| Return on Equity (ROE) | Net Income / Total Equity | ($5,000 / $60,000) = 0.083 or 8.3% | Measures the return generated on shareholder investments. A higher ROE is generally preferred. |

Ratio Interpretation and Business Implications

The interpretation of ratios is context-dependent and requires considering industry benchmarks and trends. For example, a low current ratio might be acceptable for a company with strong cash flow and readily available credit lines, but concerning for a company with inconsistent sales. Similarly, a high debt-to-equity ratio could indicate aggressive growth strategies or a higher risk profile, depending on the company’s industry and overall financial health. Analyzing ratios in conjunction with other financial data and qualitative factors provides a more comprehensive understanding of a business’s financial position and prospects. For instance, a company with a high profit margin but low ROE might be underutilizing its equity, suggesting potential for improvement in capital structure or investment strategies. Conversely, a company with a high ROE but low profit margin might be relying heavily on financial leverage to achieve high returns, potentially increasing its risk.

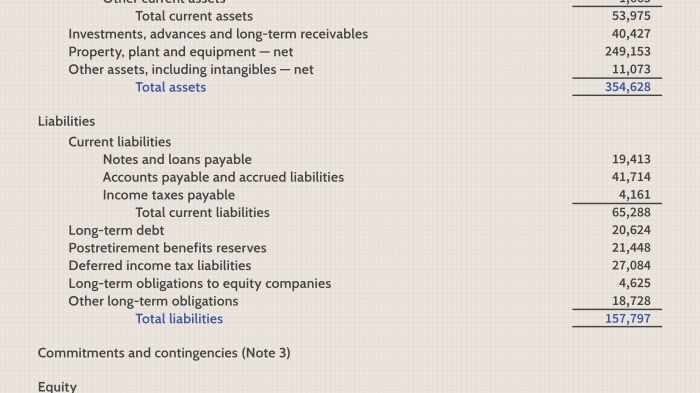

Analyzing the Balance Sheet

The balance sheet provides a snapshot of a company’s financial position at a specific point in time. Unlike the income statement, which shows performance over a period, the balance sheet illustrates the company’s assets, liabilities, and equity at a single moment. Analyzing this statement reveals crucial insights into a company’s liquidity, solvency, and overall financial health.

Balance Sheet Components

The balance sheet adheres to the fundamental accounting equation: Assets = Liabilities + Equity. Assets represent what a company owns (e.g., cash, accounts receivable, inventory, property, plant, and equipment). Liabilities represent what a company owes to others (e.g., accounts payable, loans, bonds payable). Equity represents the owners’ stake in the company (calculated as Assets – Liabilities). Analyzing each component individually and their relationship to each other is vital for a comprehensive understanding of the company’s financial standing.

Analyzing Composition and Trends in Assets, Liabilities, and Equity

Analyzing the composition of assets, liabilities, and equity involves examining the proportion of each component within the total. For instance, a high proportion of current assets relative to non-current assets might suggest a company is heavily reliant on short-term financing. Analyzing trends involves comparing these proportions over several periods (e.g., years or quarters). A consistent increase in long-term debt, for example, might signal increasing financial risk. Similarly, a declining trend in retained earnings could indicate issues with profitability or dividend payouts. These trends, when considered alongside industry benchmarks, provide valuable insights into a company’s financial trajectory.

Working Capital Analysis and Management

Working capital, calculated as Current Assets – Current Liabilities, represents a company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations. Analyzing working capital involves examining the composition of current assets (cash, accounts receivable, inventory) and current liabilities (accounts payable, short-term debt). Effective working capital management ensures sufficient liquidity to cover immediate expenses while minimizing unnecessary investment in current assets. A healthy working capital ratio (Current Assets / Current Liabilities) generally indicates strong short-term financial health. A declining working capital ratio, however, could signal potential liquidity problems.

Balance Sheet Changes and Financial Health

Changes in the balance sheet reflect a company’s financial health. For example, a significant increase in accounts receivable might indicate difficulties in collecting payments from customers, potentially impacting cash flow. Conversely, a substantial increase in retained earnings suggests profitability and reinvestment in the business. A sharp increase in long-term debt could indicate expansion or financial distress, depending on the context. Analyzing these changes in relation to the income statement and cash flow statement provides a more holistic view of the company’s performance and financial stability.

Hypothetical Balance Sheet Example and Analysis

Let’s consider a simplified hypothetical balance sheet for “XYZ Company” as of December 31, 2023:

| Assets | Amount | Liabilities & Equity | Amount |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Assets: | Current Liabilities: | ||

| Cash | $10,000 | Accounts Payable | $5,000 |

| Accounts Receivable | $20,000 | Short-term Debt | $10,000 |

| Inventory | $15,000 | Total Current Liabilities | $15,000 |

| Non-Current Assets: | Non-Current Liabilities: | ||

| Property, Plant & Equipment | $50,000 | Long-term Debt | $25,000 |

| Total Assets | $95,000 | Equity: | |

| Common Stock | $20,000 | ||

| Retained Earnings | $30,000 | ||

| Total Liabilities & Equity | $95,000 |

Potential Issues: XYZ Company’s current ratio (Current Assets / Current Liabilities = 2) appears healthy. However, a significant portion of its assets are tied up in inventory ($15,000), which might indicate slow sales or inefficient inventory management. High accounts receivable ($20,000) also raises concerns about collection efficiency. A more detailed analysis, including comparing these figures to industry benchmarks and past performance, is needed for a complete assessment. Potential Strengths: The company possesses significant non-current assets ($50,000), indicating a solid foundation for future growth. Furthermore, a healthy level of retained earnings ($30,000) suggests profitability and financial stability.

Analyzing the Income Statement

The income statement, also known as the profit and loss (P&L) statement, provides a snapshot of a company’s financial performance over a specific period. Understanding its components and analyzing its trends is crucial for assessing a company’s profitability and overall health. This analysis complements the balance sheet analysis by providing a dynamic view of how the company generates revenue and manages its expenses.

Income Statement Components

The income statement primarily consists of three key elements: revenues, expenses, and net income. Revenues represent the total income generated from the company’s primary operations. Expenses encompass all costs incurred in generating those revenues, including cost of goods sold, operating expenses, and interest expenses. Net income, the bottom line, is the difference between total revenues and total expenses. A positive net income indicates profitability, while a negative net income represents a loss.

Analyzing Revenue Streams and Sales Trends

Analyzing revenue streams involves examining the sources of revenue and identifying trends in sales growth or decline. This can be done by comparing revenue figures across different periods, identifying the contribution of each revenue segment, and analyzing the impact of factors like pricing changes, sales volume, and market conditions. For instance, a company might see a decline in revenue from one product line but growth in another, highlighting the need for strategic adjustments. Consistent year-over-year growth suggests a healthy business model, while declining revenues may indicate underlying issues requiring investigation. Visual representations, such as line graphs showing revenue over time, are highly beneficial in identifying trends.

Analyzing Cost Structures and Identifying Areas for Improvement

Analyzing cost structures involves examining the different types of expenses and their proportions relative to revenue. This analysis helps in identifying areas where costs can be reduced or controlled more effectively. For example, a detailed breakdown of cost of goods sold can reveal opportunities for negotiating better prices with suppliers or improving production efficiency. Similarly, analyzing operating expenses can highlight areas where streamlining processes or reducing administrative overhead might improve profitability. Comparing cost structures to industry benchmarks can also provide valuable insights into areas for improvement.

Analyzing Profitability Ratios

Profitability ratios provide valuable insights into a company’s ability to generate profit from its operations. Key ratios include:

- Gross Profit Margin: (Revenue – Cost of Goods Sold) / Revenue. This indicates the profitability of a company’s core operations before considering operating expenses.

- Net Profit Margin: Net Income / Revenue. This reflects the overall profitability after all expenses are deducted.

Analyzing these ratios over time and comparing them to industry averages helps assess the company’s performance and identify potential areas of concern. A declining gross profit margin might suggest rising input costs or increasing competition, while a declining net profit margin might indicate rising operating expenses.

Sample Income Statement Analysis

The following table demonstrates the analysis of a hypothetical income statement for ABC Company:

| Item | Year 1 | Year 2 | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Revenue | $1,000,000 | $1,200,000 | 20% Revenue Growth |

| Cost of Goods Sold | $600,000 | $700,000 | 16.7% increase in COGS |

| Gross Profit | $400,000 | $500,000 | 25% Gross Profit Growth |

| Operating Expenses | $200,000 | $250,000 | 25% increase in Operating Expenses |

| Net Income | $200,000 | $250,000 | 25% Net Income Growth |

While revenue and net income grew significantly, the analysis reveals a faster growth in operating expenses compared to gross profit. This warrants further investigation into the reasons behind the increase in operating expenses. Further analysis could involve examining individual expense categories to pinpoint specific areas for improvement.

Analyzing the Cash Flow Statement

The cash flow statement provides a crucial insight into a company’s liquidity and financial health, offering a dynamic view beyond the static picture presented by the balance sheet and income statement. It details the inflows and outflows of cash during a specific period, revealing how a company generates and utilizes its cash resources. Understanding this statement is vital for assessing a company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations, fund its operations, and invest in future growth.

Components of the Cash Flow Statement

The cash flow statement is typically divided into three main sections: operating activities, investing activities, and financing activities. Operating activities represent the cash flows generated from a company’s core business operations, such as sales and purchases. Investing activities involve cash flows related to acquiring or disposing of long-term assets, such as property, plant, and equipment (PP&E). Financing activities encompass cash flows related to raising capital, such as issuing debt or equity, and repaying debt. These three sections provide a comprehensive picture of a company’s cash flow sources and uses.

Analyzing Cash Flows from Operating Activities

Analyzing cash flows from operating activities helps determine the efficiency and profitability of a company’s core business. A strong positive cash flow from operations indicates the business is generating sufficient cash to cover its expenses and reinvest in its growth. Conversely, negative cash flow from operations may signal underlying problems with profitability or efficiency. Analyzing changes in working capital, such as accounts receivable and inventory, is crucial for understanding the drivers of cash flow from operations. For example, a significant increase in accounts receivable might indicate difficulties in collecting payments from customers, impacting the overall cash flow.

Analyzing Cash Flows from Investing Activities

Analyzing cash flows from investing activities reveals a company’s investment strategies and capital expenditure plans. Significant capital expenditures (CapEx) suggest investments in future growth, while negative cash flows may reflect asset sales or divestitures. Analyzing the pattern of investing activities over time can provide insights into a company’s long-term growth prospects and strategic direction. For instance, consistent investment in research and development (R&D) might indicate a commitment to innovation and future market leadership. Conversely, a lack of investment might signal a lack of future growth opportunities.

Analyzing Cash Flows from Financing Activities

Analyzing cash flows from financing activities shows how a company funds its operations and investments. Positive cash flow in this section may indicate the company is successfully raising capital through debt or equity financing. Negative cash flow might reflect debt repayments or dividend payments. A consistent reliance on debt financing may raise concerns about the company’s financial risk, while a consistent pattern of equity financing could signal a healthy financial position. For example, a significant increase in debt financing coupled with declining cash flow from operations could indicate a risky financial strategy.

Analyzing Free Cash Flow

Free cash flow (FCF) represents the cash flow available to a company after deducting capital expenditures and other essential investments. It is calculated as:

Free Cash Flow = Cash Flow from Operations – Capital Expenditures

Analyzing FCF is crucial because it indicates the cash a company has available for debt repayment, dividends, share repurchases, and other strategic initiatives. A healthy FCF is a strong indicator of financial strength and future growth potential. A declining FCF, however, may signal financial distress or a lack of investment opportunities. For instance, a company with consistently high FCF can afford to invest in new projects, acquire other companies, or return capital to shareholders through dividends or share buybacks.

Cash Flow and Financial Health

Changes in cash flow directly reflect a company’s financial health and liquidity. Consistent positive cash flow from operations demonstrates strong profitability and efficient management of working capital. A company with strong cash flow is better equipped to weather economic downturns, meet its financial obligations, and pursue growth opportunities. Conversely, declining cash flow, particularly from operating activities, is a significant warning sign that the company may be facing financial difficulties. For example, a company experiencing consistent losses might still show positive cash flow if it is aggressively reducing its inventory and delaying payments to suppliers; however, this is not a sustainable long-term strategy.

Interpreting the Cash Flow Statement for Risk and Opportunity Identification

Analyzing the cash flow statement can reveal potential risks and opportunities. For example, a significant increase in accounts payable might indicate the company is struggling to pay its suppliers, posing a credit risk. On the other hand, a large increase in cash from financing activities could signal potential opportunities for expansion or acquisitions. By carefully analyzing the trends and patterns in the cash flow statement, investors and analysts can identify potential risks and opportunities, making informed decisions about the company’s future prospects. For example, a company consistently investing in R&D with a strong FCF might be positioned for significant future growth, while a company with declining cash flow from operations and increasing debt levels might be at risk of financial distress.

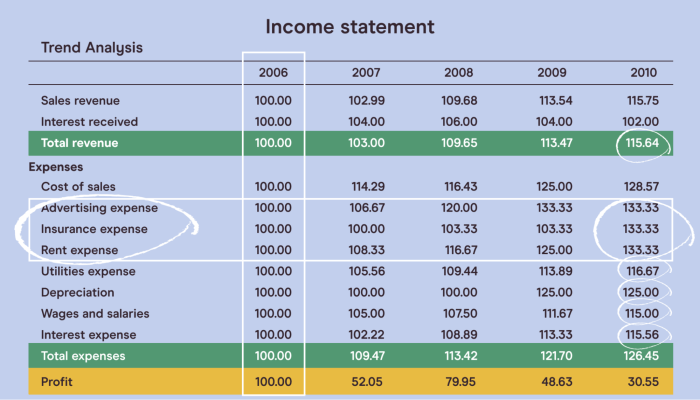

Trend Analysis and Forecasting

Trend analysis in financial statement examination involves identifying patterns and changes in a company’s financial performance over time. This helps assess the company’s growth trajectory, stability, and potential risks. By analyzing historical data, we can gain valuable insights into a company’s strengths and weaknesses, and make more informed predictions about its future financial performance. This analysis is crucial for investors, creditors, and management in making strategic decisions.

Methods for Identifying Trends in Financial Data

Several methods exist for identifying trends within financial data. These methods rely on analyzing historical financial statements over multiple periods, typically several years. Visual representations, such as line graphs, are often employed to highlight these trends. Simple calculations, such as year-over-year growth rates, are also commonly used. More sophisticated statistical techniques, including regression analysis, can provide more precise estimations of trends and their underlying factors. For example, plotting revenue figures over five years on a line graph immediately reveals whether revenue is increasing, decreasing, or remaining relatively stable. Calculating the percentage change in revenue year-over-year provides a quantifiable measure of growth or decline.

Techniques for Forecasting Future Financial Performance

Forecasting future performance utilizes historical trends identified through trend analysis. Several techniques can be employed, each with its own strengths and limitations. Simple methods include extrapolating past trends, assuming a consistent rate of growth or decline. More complex methods incorporate various factors, such as industry trends, economic conditions, and company-specific initiatives. Time series analysis, a statistical method, can be applied to project future values based on past data and identified patterns. For instance, a company with consistently increasing sales by an average of 10% annually might project future sales based on this historical trend, though adjustments might be needed to account for external factors like a potential economic downturn.

Examples of Trend Analysis in Business Decision-Making

Trend analysis plays a critical role in various business decisions. For example, a consistent decline in gross profit margin might prompt management to review its pricing strategy or explore cost-cutting measures. A sustained increase in accounts receivable could indicate problems with credit collection, requiring a review of credit policies. Similarly, an upward trend in debt-to-equity ratio could signal increasing financial risk, prompting a reassessment of the company’s capital structure. Conversely, a consistent increase in return on equity (ROE) could indicate effective management and strong financial health.

Hypothetical Trend Analysis Example

Imagine a hypothetical trend analysis of a company’s net income over five years. The data, displayed as a line graph, shows net income starting at $1 million in Year 1, rising to $1.2 million in Year 2, then $1.5 million in Year 3, followed by a slight dip to $1.4 million in Year 4, and finally reaching $1.7 million in Year 5. The graph clearly shows an overall upward trend in net income, despite a minor setback in Year 4. This observation suggests positive growth, though the Year 4 dip warrants further investigation into potential underlying causes, such as a temporary market downturn or one-time expense. The overall positive trend, however, indicates a healthy financial outlook.

Limitations of Financial Statement Examination

Financial statement analysis, while a powerful tool for evaluating a business’s financial health, is not without its limitations. Relying solely on these statements can lead to incomplete or even misleading conclusions. A comprehensive assessment necessitates considering qualitative factors alongside the quantitative data presented in the statements.

Limitations of Using Financial Statements Alone

Financial statements provide a snapshot of a company’s financial position at a specific point in time (balance sheet) or over a period (income statement and cash flow statement). They offer a quantitative view, but crucial qualitative aspects, such as management quality, employee morale, brand reputation, and industry dynamics, are not reflected. For example, a company might show strong financial performance on paper, but be facing significant challenges related to its product’s obsolescence or a looming lawsuit. Ignoring these qualitative factors could lead to a flawed assessment of the company’s true value and future prospects. This highlights the need for a holistic approach, combining quantitative analysis with in-depth qualitative research.

The Importance of Qualitative Factors

Qualitative factors are non-numerical aspects that significantly influence a company’s performance and future outlook. These factors, while not directly reflected in financial statements, can substantially affect the interpretation of the quantitative data. For instance, a company with strong financial ratios might be experiencing internal conflicts affecting productivity and potentially harming future earnings. Similarly, a strong brand reputation can command premium pricing and increase market share, impacting profitability beyond what the financial statements might immediately reveal. Ignoring these crucial non-financial elements results in an incomplete and potentially inaccurate picture of the business’s overall health and potential.

Potential for Manipulation or Misrepresentation

The inherent flexibility within generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) allows for some degree of manipulation or misrepresentation of financial information. Creative accounting practices, such as aggressive revenue recognition or the improper capitalization of expenses, can paint a rosier picture than reality. While auditing aims to mitigate this risk, sophisticated schemes can still evade detection. For example, a company might overstate its accounts receivable, artificially inflating its revenue. This underlines the importance of critical evaluation of financial statements and the need to scrutinize the notes to the financial statements for potential inconsistencies or unusual transactions.

The Role of Auditing and Independent Verification

Independent audits provide an essential layer of verification and enhance the reliability of financial statements. Auditors, acting as independent third parties, examine a company’s financial records to ensure compliance with accounting standards and the accuracy of the reported information. While not foolproof, the presence of an independent audit provides a degree of assurance that the financial statements are a fair representation of the company’s financial position. The auditor’s report, included with the financial statements, highlights any significant limitations or concerns identified during the audit process. The level of assurance provided by an audit can vary depending on the scope and nature of the audit itself.

Impact of Accounting Standards and Variations

Different countries and jurisdictions may adopt varying accounting standards, leading to inconsistencies in the presentation and interpretation of financial statements. Comparing companies from different countries requires careful consideration of these differences. For example, the adoption of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) versus US Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) can lead to significant variations in how certain transactions are recorded and reported. This necessitates a thorough understanding of the specific accounting standards used when analyzing financial statements from different entities. Failure to account for these variations can lead to erroneous comparisons and potentially flawed conclusions.

Ending Remarks

Mastering financial statement analysis is a journey, not a destination. The ability to critically assess a company’s financial position empowers informed decision-making, whether you are an investor evaluating potential opportunities, a creditor assessing creditworthiness, or a manager seeking to optimize performance. While this guide provides a solid foundation, continuous learning and adaptation are crucial in this ever-evolving financial landscape. Remember that context is key, and a holistic understanding of a company, including its industry and competitive environment, is essential for accurate and meaningful interpretation of its financial statements.

Detailed FAQs

What are the limitations of using only financial ratios for analysis?

Financial ratios provide a valuable snapshot, but they don’t tell the whole story. They should be used in conjunction with qualitative factors like management quality, industry trends, and economic conditions for a complete picture.

How frequently should financial statements be analyzed?

The frequency depends on the context. For short-term investors, frequent analysis (e.g., quarterly) might be necessary. Long-term investors might analyze annually or even less frequently.

What is the difference between accrual and cash accounting when analyzing statements?

Accrual accounting recognizes revenue and expenses when earned or incurred, regardless of cash flow. Cash accounting recognizes revenue and expenses only when cash changes hands. Understanding the method used is crucial for accurate interpretation.

How can I identify potential accounting irregularities or manipulation?

Look for inconsistencies in ratios over time, unusual changes in account balances, and discrepancies between reported numbers and industry benchmarks. Independent audits and knowledge of accounting standards are also crucial.