Crafting a successful investment portfolio isn’t simply about accumulating assets; it’s about strategically aligning investments with individual financial goals and risk tolerance. Investment portfolio optimization delves into the science and art of maximizing returns while mitigating risk, a crucial aspect for securing long-term financial well-being. This exploration will uncover the key principles, models, and practical strategies employed in optimizing investment portfolios for diverse investor profiles.

Understanding your personal risk tolerance, defining clear financial objectives, and selecting appropriate asset classes are foundational steps. The process involves analyzing historical data, employing sophisticated models, and regularly rebalancing the portfolio to adapt to market fluctuations. This comprehensive guide will equip you with the knowledge to navigate the complexities of portfolio optimization and make informed investment decisions.

Defining Investment Portfolio Optimization

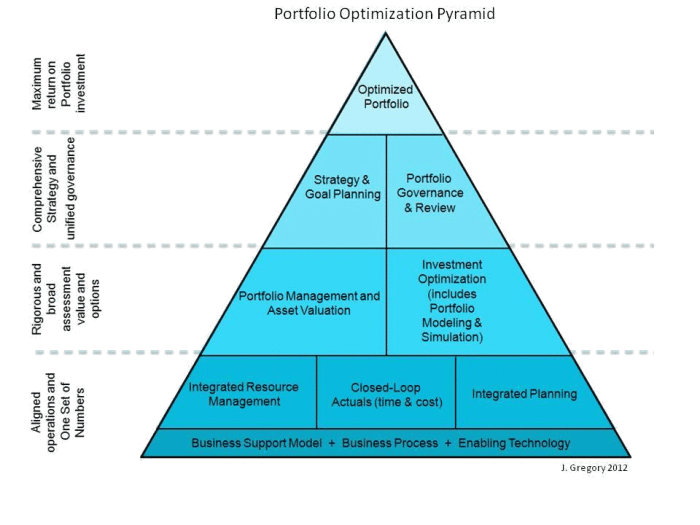

Investment portfolio optimization is the process of constructing an investment portfolio that best aligns with an investor’s specific financial goals and risk tolerance. It involves strategically allocating assets across different investment vehicles to achieve the desired balance between risk and return. This process goes beyond simply diversifying investments; it leverages quantitative techniques to identify the optimal allocation that maximizes expected returns for a given level of risk, or minimizes risk for a given level of expected return.

The core principles underpinning portfolio optimization revolve around diversification, risk assessment, and return expectation. Diversification reduces the impact of any single investment’s underperformance on the overall portfolio. Risk assessment involves quantifying the potential variability of returns, often using measures like standard deviation or beta. Return expectation considers the potential growth of different assets based on historical data, market forecasts, and economic conditions. These elements are combined to create a portfolio tailored to the investor’s individual needs.

Investor Goals in Portfolio Optimization

Investors pursue various goals when optimizing their portfolios. Maximizing returns is a common objective, aiming for the highest possible growth of capital. However, this often comes with increased risk. Minimizing risk, on the other hand, prioritizes capital preservation and stability, often accepting lower potential returns. Many investors aim to meet specific financial goals, such as funding retirement, purchasing a home, or paying for education. These goals influence the time horizon and risk tolerance of the investment strategy. For example, a young investor with a long time horizon might tolerate higher risk to pursue potentially higher returns, while an investor nearing retirement might prioritize capital preservation and choose a more conservative approach.

Investor Profiles and Optimization Strategies

Different investor profiles require distinct portfolio optimization strategies. The following table illustrates this:

| Investor Profile | Risk Tolerance | Investment Goals | Optimization Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative Investor | Low | Capital preservation, stable income | Focus on low-risk investments like government bonds, high-quality corporate bonds, and dividend-paying stocks. Optimization might prioritize minimizing volatility and ensuring consistent income streams. |

| Moderate Investor | Medium | Balance between growth and preservation, long-term wealth building | Diversified portfolio including a mix of stocks, bonds, and potentially real estate. Optimization might aim for a balance between risk and return, using techniques like mean-variance optimization to find the efficient frontier. |

| Aggressive Investor | High | High growth, potentially higher risk | Significant allocation to stocks, potentially including emerging markets and small-cap companies. Optimization might focus on maximizing expected return, even if it means accepting higher volatility. Alternative investments like private equity or hedge funds might also be considered. |

| Retirement Investor (near retirement) | Low to Medium | Secure retirement income, capital preservation | Conservative approach with a focus on generating income and preserving principal. Optimization might emphasize minimizing downside risk and generating a reliable stream of income through fixed-income securities and dividend-paying stocks. |

Key Factors Influencing Portfolio Optimization

Portfolio optimization is a dynamic process, constantly influenced by a variety of interacting factors. Understanding these factors is crucial for constructing and maintaining a portfolio aligned with an investor’s goals and risk tolerance. Ignoring these influences can lead to suboptimal performance and increased risk.

Market Conditions

Market conditions significantly impact portfolio optimization strategies. Economic growth, inflation rates, interest rates, and geopolitical events all play a role. For instance, during periods of high inflation, investors might shift towards assets that are expected to hedge against inflation, such as real estate or commodities. Conversely, during economic downturns, a more conservative approach with a higher allocation to bonds might be preferred. Analyzing market trends and anticipating potential shifts is vital for adjusting portfolio allocations proactively.

Investor Risk Tolerance

An investor’s risk tolerance is a paramount factor. This reflects their comfort level with potential losses in pursuit of higher returns. Risk tolerance is subjective and influenced by factors such as age, financial goals, and personal circumstances. A younger investor with a longer time horizon might be comfortable with a higher proportion of equities in their portfolio, accepting higher risk for potentially greater returns. Conversely, an older investor nearing retirement might prefer a more conservative approach with a greater allocation to fixed-income securities to preserve capital. Accurately assessing and incorporating risk tolerance is essential for creating a suitable portfolio.

Time Horizon

The investor’s time horizon, or the period over which they plan to invest, significantly impacts portfolio construction. Longer time horizons allow for greater risk-taking as there’s more time to recover from potential losses. A shorter time horizon necessitates a more conservative approach, prioritizing capital preservation over potentially higher returns. For example, an investor saving for retirement in 30 years can afford a higher equity allocation than someone saving for a down payment on a house in 3 years.

Diversification’s Impact on Portfolio Performance

Diversification is a cornerstone of portfolio optimization. It involves spreading investments across different asset classes, sectors, and geographies to reduce overall portfolio risk. A diversified portfolio aims to minimize the impact of poor performance in one area by offsetting it with potentially better performance in another.

Consider two hypothetical portfolios:

- Non-diversified Portfolio: This portfolio might consist entirely of shares in a single company. While offering the potential for high returns if the company thrives, it also carries significant risk. If the company performs poorly, the entire portfolio suffers dramatically.

- Diversified Portfolio: This portfolio includes a mix of stocks (across various sectors and market capitalizations), bonds (government and corporate), real estate investment trusts (REITs), and potentially commodities. This approach significantly reduces the risk associated with any single investment underperforming.

Comparing risk-return profiles, the diversified portfolio typically exhibits lower volatility (lower risk) compared to the non-diversified portfolio, although the potential return might be slightly lower in the absence of a high-performing single investment.

Advantages and disadvantages of diversification:

- Advantages:

- Reduced risk: Lower volatility and potential for loss.

- Improved risk-adjusted returns: Higher returns relative to the level of risk taken.

- Increased stability: Smoother portfolio performance over time.

- Disadvantages:

- Lower potential returns (compared to a highly concentrated portfolio): Diversification may slightly reduce the potential for exceptionally high returns.

- Increased complexity: Managing a diversified portfolio requires more research and effort.

Hypothetical Diversified Portfolio

This example illustrates a diversified portfolio, although specific allocations should be tailored to individual circumstances:

| Asset Class | Allocation (%) |

|---|---|

| US Equities (Large-Cap) | 30 |

| US Equities (Small-Cap) | 10 |

| International Equities | 15 |

| US Government Bonds | 20 |

| Corporate Bonds | 10 |

| Real Estate (REITs) | 10 |

| Commodities (Gold) | 5 |

This portfolio demonstrates diversification across asset classes, aiming to balance risk and return. The allocation percentages are illustrative and can be adjusted based on individual risk tolerance and market conditions. It is important to remember that past performance is not indicative of future results, and regular rebalancing is crucial to maintain the desired asset allocation.

Portfolio Optimization Models and Techniques

Portfolio optimization aims to construct an investment portfolio that maximizes returns for a given level of risk or minimizes risk for a given level of return. Several models and techniques exist to achieve this goal, each with its own assumptions, strengths, and weaknesses. Understanding these differences is crucial for selecting the most appropriate model for a specific investment objective and risk tolerance.

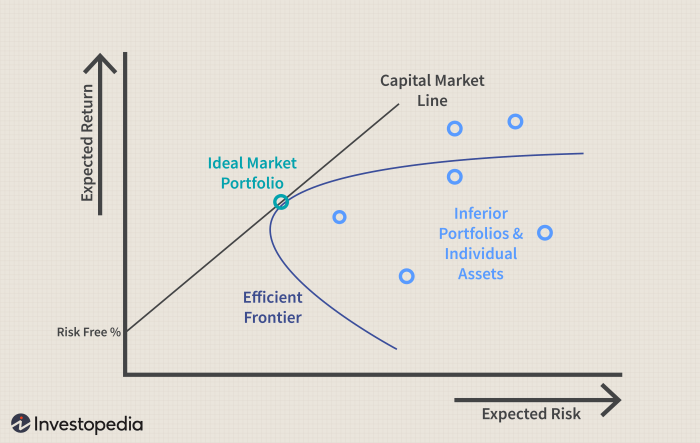

Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) and Mean-Variance Optimization

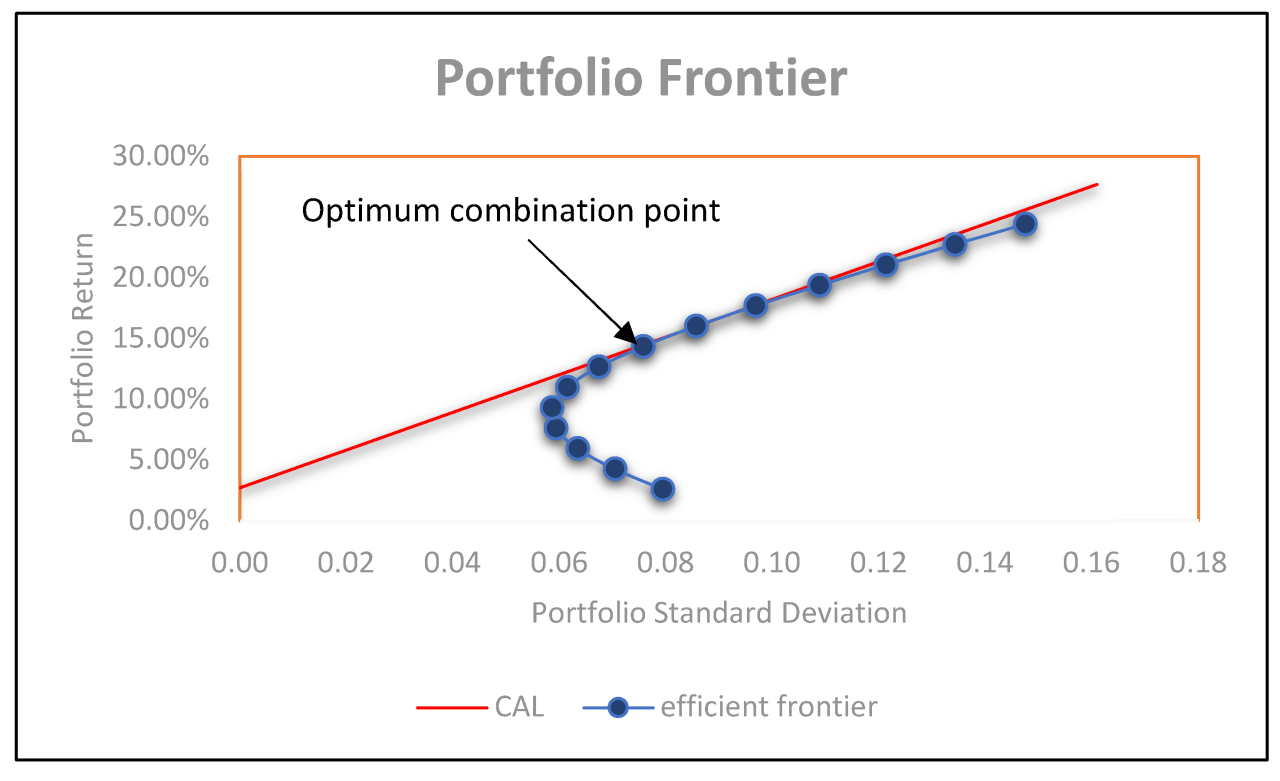

Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT), pioneered by Harry Markowitz, forms the foundation of many portfolio optimization techniques. At its core, MPT uses mean-variance optimization to construct efficient portfolios. This involves calculating the expected return and variance (a measure of risk) for each asset and then combining them to find the portfolio with the highest expected return for a given level of risk, or the lowest risk for a given expected return. The efficient frontier, a graphical representation of these optimal portfolios, is a key output of MPT.

Assumptions and Limitations of MPT and Mean-Variance Optimization

MPT relies on several key assumptions, including the normality of asset returns, the availability of accurate estimates of expected returns and covariances, and the investor’s preference for maximizing expected return and minimizing risk. However, these assumptions are often violated in practice. Real-world asset returns are frequently not normally distributed, exhibiting skewness and kurtosis (fat tails). Furthermore, accurately estimating expected returns and covariances is challenging, especially over longer time horizons. The reliance on historical data can lead to inaccurate predictions, particularly during periods of market upheaval. Another limitation is that MPT assumes investors are risk-averse and only consider mean and variance, neglecting other higher-order moments of the return distribution that might be relevant.

Black-Litterman Model

The Black-Litterman model addresses some of the limitations of MPT by incorporating investor views. Instead of relying solely on historical data to estimate expected returns, the Black-Litterman model allows investors to input their own subjective views or forecasts, which are then combined with the market equilibrium returns derived from MPT. This approach reduces the reliance on potentially inaccurate historical data and allows for a more personalized portfolio optimization process. The model incorporates investor views in a Bayesian framework, blending subjective beliefs with market equilibrium.

Comparison of Portfolio Optimization Models

The following table summarizes the key features of the discussed models:

| Model Name | Key Assumptions | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) / Mean-Variance Optimization | Normality of asset returns, accurate estimates of expected returns and covariances, risk aversion, mean-variance utility | Provides a mathematically rigorous framework for portfolio construction, identifies efficient portfolios, widely understood and used | Relies on potentially inaccurate estimates of expected returns and covariances, assumes normality of returns (often violated), ignores higher-order moments of the return distribution |

| Black-Litterman Model | Similar to MPT, but incorporates investor views, Bayesian framework | Reduces reliance on historical data, allows for personalization, incorporates investor expertise | Requires careful specification of investor views, can be computationally intensive, still relies on some assumptions about asset return distributions |

Practical Application of Portfolio Optimization

Portfolio optimization theory is valuable only when applied to real-world investment decisions. This section demonstrates how historical data can be used to build optimized portfolios, outlining the process step-by-step and providing a concrete example. We’ll focus on using readily available data and simplified models to illustrate the core concepts. Remember that real-world applications often involve more sophisticated techniques and considerations.

Estimating Asset Returns and Correlations

Accurate estimations of asset returns and correlations are crucial for effective portfolio optimization. Historical data provides a starting point, though it’s important to acknowledge its limitations. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results. However, using historical data allows us to explore different scenarios and understand the potential impact of various asset classes on portfolio performance. We can obtain historical data from various financial data providers such as Yahoo Finance, Google Finance, or Bloomberg.

We can estimate returns using historical average returns. For example, if we have five years of monthly returns for a particular stock, we can calculate the average monthly return and annualize it. Correlations are estimated using the covariance matrix, which measures how the returns of different assets move together. The correlation coefficient, derived from the covariance, ranges from -1 (perfect negative correlation) to +1 (perfect positive correlation), with 0 indicating no linear relationship.

Building an Optimized Portfolio: A Step-by-Step Guide

The following steps illustrate the process of building an optimized portfolio using the mean-variance optimization model. This model aims to maximize expected return for a given level of risk (or minimize risk for a given expected return).

- Step 1: Data Collection: Gather historical return data for the assets under consideration. This could include stocks, bonds, real estate, etc. The longer the time horizon, the more reliable the estimates, but data quality should always be considered.

- Step 2: Return and Covariance Calculation: Calculate the historical average returns and the covariance matrix for the selected assets. Various software packages (e.g., Excel, R, Python) can be used for these calculations.

- Step 3: Defining Risk Tolerance: Determine the investor’s risk tolerance. This is crucial and often requires a detailed discussion with the investor. Risk tolerance can be expressed through a maximum acceptable standard deviation or a minimum acceptable Sharpe ratio (a risk-adjusted measure of return).

- Step 4: Optimization: Use a portfolio optimization solver (available in many software packages) to find the optimal asset allocation that maximizes expected return given the specified risk tolerance or minimizes risk for a given expected return.

- Step 5: Portfolio Construction: Based on the optimized weights, construct the portfolio by allocating capital to each asset accordingly.

- Step 6: Monitoring and Rebalancing: Regularly monitor the portfolio’s performance and rebalance it periodically to maintain the desired asset allocation. Market fluctuations will cause the weights to deviate over time.

Example: Portfolio for a Young Investor

Consider a young investor (age 30) with a long time horizon (30+ years) and a high risk tolerance. This investor can afford to take on more risk in pursuit of higher potential returns. A suitable portfolio might be:

| Asset Class | Allocation (%) | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Equities (US and International) | 70 | Higher growth potential to benefit from long time horizon. Diversification across geographies reduces risk. |

| Bonds (Government and Corporate) | 20 | Provides some stability and downside protection. |

| Alternative Investments (e.g., Real Estate) | 10 | Adds diversification and potential for higher returns (though also higher risk). |

The high equity allocation reflects the long time horizon, allowing for recovery from potential market downturns. The inclusion of bonds and alternative investments provides diversification and reduces overall portfolio volatility. This is a simplified example, and a real-world application would require a more detailed analysis considering specific market conditions and the investor’s individual circumstances. The choice of specific equities and bonds would also require further research and selection.

Risk Management in Portfolio Optimization

Risk management is an integral part of portfolio optimization, aiming to balance the pursuit of higher returns with the acceptance of a reasonable level of risk. A well-defined risk management strategy is crucial for achieving long-term investment goals while mitigating potential losses. Ignoring risk can lead to significant financial setbacks, highlighting the importance of incorporating risk measures and mitigation strategies into the optimization process.

Risk Measures in Portfolio Optimization

Several key metrics quantify and assess risk within a portfolio. These measures inform the optimization process by allowing investors to tailor their portfolios to their specific risk tolerance. Understanding these measures is crucial for making informed decisions about asset allocation and diversification.

Standard deviation measures the volatility of returns, indicating the dispersion of actual returns around the expected return. A higher standard deviation signifies greater risk. Beta, on the other hand, measures the systematic risk of an asset relative to the market. A beta greater than 1 suggests higher volatility than the market, while a beta less than 1 indicates lower volatility. The Sharpe ratio considers both risk and return, providing a risk-adjusted measure of performance. It calculates the excess return per unit of risk (standard deviation). A higher Sharpe ratio indicates better risk-adjusted performance. These metrics are used in optimization models to construct portfolios that achieve the desired balance between risk and return. For example, an investor with a low risk tolerance might prioritize portfolios with lower standard deviations and betas, even if it means accepting lower expected returns.

Techniques for Managing Market Risk

Market risk, also known as systematic risk, stems from broad market movements and cannot be fully diversified away. Effectively managing market risk is paramount for portfolio stability.

Several strategies exist to mitigate market risk. These strategies often involve diversification across different asset classes, sectors, and geographies.

- Diversification: Spreading investments across various asset classes (e.g., stocks, bonds, real estate) and sectors reduces the impact of market fluctuations on the overall portfolio. For example, a portfolio holding both stocks and bonds is less susceptible to market downturns than a portfolio solely invested in stocks.

- Hedging: Using financial instruments, such as derivatives (e.g., options, futures), to offset potential losses from adverse market movements. For example, a long position in a stock can be hedged with a short put option, limiting potential downside risk.

- Strategic Asset Allocation: Proactively adjusting the portfolio’s asset allocation based on market forecasts and long-term economic outlook. For instance, reducing equity exposure during periods of anticipated market decline and increasing it during anticipated market growth.

Techniques for Managing Credit Risk

Credit risk arises from the possibility of borrowers defaulting on their debt obligations. This risk is particularly relevant for investments in bonds and loans.

Mitigating credit risk requires a careful assessment of the creditworthiness of borrowers and diversification across different issuers.

- Credit Rating Analysis: Assessing the creditworthiness of borrowers using credit ratings provided by agencies like Moody’s, S&P, and Fitch. Investing in higher-rated bonds generally reduces credit risk.

- Diversification across Issuers: Spreading investments across multiple borrowers reduces the impact of a single default. A portfolio holding bonds issued by various companies and governments is less vulnerable to a single issuer’s default.

- Due Diligence: Thoroughly investigating the financial health and credit history of borrowers before investing. This can involve reviewing financial statements, conducting industry research, and analyzing macroeconomic conditions.

Techniques for Managing Interest Rate Risk

Interest rate risk stems from fluctuations in interest rates, impacting the value of fixed-income securities. Rising interest rates typically lead to a decline in the value of bonds, while falling interest rates have the opposite effect.

Managing interest rate risk involves understanding the duration and maturity of fixed-income investments and strategically adjusting the portfolio’s duration to align with the investor’s risk tolerance.

- Duration Matching: Matching the duration of the bond portfolio to the investor’s investment horizon. This minimizes the impact of interest rate changes on the portfolio’s value. For example, an investor with a short-term investment horizon might choose bonds with shorter durations.

- Immunization: Constructing a portfolio that is insensitive to interest rate changes within a specific range. This involves carefully selecting bonds with varying maturities and durations.

- Interest Rate Derivatives: Using derivatives such as interest rate swaps or futures to hedge against interest rate risk. These instruments can be used to lock in interest rates or to profit from anticipated interest rate movements.

Rebalancing and Monitoring the Portfolio

Maintaining an optimized investment portfolio isn’t a one-time event; it requires ongoing attention. Regular rebalancing and diligent monitoring are crucial to ensuring your portfolio remains aligned with your investment goals and risk tolerance over time. This involves periodically adjusting your asset allocation to restore your target percentages, and actively tracking its performance to identify areas needing attention.

Portfolio rebalancing is the process of adjusting your asset allocation back to your original target percentages. This involves selling some assets that have performed well and buying more of those that have underperformed. While it may seem counterintuitive to sell winners, this strategy helps maintain your desired risk level and capitalize on market fluctuations. Without rebalancing, a portfolio can drift significantly from its intended allocation, potentially exposing the investor to unintended levels of risk.

Rebalancing Strategies

Several strategies exist for rebalancing a portfolio. The frequency of rebalancing depends on factors like your investment goals, risk tolerance, and the volatility of your assets.

- Calendar-Based Rebalancing: This involves rebalancing your portfolio at fixed intervals, such as annually, semi-annually, or quarterly. This approach is straightforward and easy to implement.

- Percentage-Based Rebalancing: This strategy involves rebalancing when the allocation of your assets deviates from your target percentages by a predetermined threshold (e.g., 5% or 10%). This method is more reactive to market changes.

- Threshold-Based Rebalancing: This is a hybrid approach that combines calendar-based and percentage-based rebalancing. For instance, you might rebalance annually, but only if the deviation from your target allocation exceeds a certain percentage.

Monitoring Portfolio Performance and Making Adjustments

Monitoring involves regularly reviewing your portfolio’s performance against your benchmarks and goals. This includes tracking key metrics like returns, risk, and asset allocation. Tools like portfolio tracking software or brokerage account statements can assist in this process. Identifying significant deviations from your plan allows for timely adjustments to your strategy. These adjustments might include shifting asset allocation, adjusting the investment timeline, or even changing your overall investment strategy based on new information or market conditions.

Hypothetical Scenario: Rebalancing Benefits

Let’s consider a hypothetical portfolio initially invested equally in stocks (50%) and bonds (50%), with a target allocation remaining at 50/50. Assume an initial investment of $10,000. Over three years, stocks outperform bonds significantly.

| Year | Stocks (No Rebalancing) | Bonds (No Rebalancing) | Total (No Rebalancing) | Stocks (Rebalanced) | Bonds (Rebalanced) | Total (Rebalanced) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | $5,000 | $5,000 | $10,000 | $5,000 | $5,000 | $10,000 |

| 1 | $6,000 | $4,800 | $10,800 | $5,400 | $5,400 | $10,800 |

| 2 | $7,200 | $4,608 | $11,808 | $5,940 | $5,868 | $11,808 |

| 3 | $8,640 | $4,478.72 | $13,118.72 | $6,559.36 | $6,559.36 | $13,118.72 |

This illustrates that while the total portfolio value is the same in both scenarios, the rebalanced portfolio maintains a more consistent risk profile and avoids overexposure to the better-performing asset class. Over longer periods, the benefits of rebalancing can be even more pronounced.

Conclusion

Ultimately, effective investment portfolio optimization is a dynamic process requiring ongoing monitoring and adaptation. By understanding the core principles, employing appropriate models, and diligently managing risk, investors can significantly enhance their chances of achieving their financial aspirations. The journey involves careful planning, continuous learning, and a proactive approach to adapting to changing market conditions and personal circumstances. Remember, professional financial advice is always recommended for personalized guidance.

FAQ

What is the difference between active and passive portfolio management?

Active management involves actively trading securities to outperform the market, while passive management focuses on holding a diversified portfolio that mirrors a market index, requiring less frequent trading.

How often should I rebalance my portfolio?

Rebalancing frequency depends on your investment strategy and risk tolerance. Common schedules range from annually to quarterly, aiming to maintain your target asset allocation.

What are some common mistakes to avoid in portfolio optimization?

Common mistakes include ignoring diversification, emotional investing (panic selling or chasing trends), failing to rebalance, and neglecting risk management.

How can I determine my appropriate risk tolerance?

Consider your investment timeline, financial goals, and comfort level with potential losses. Online risk tolerance questionnaires and consultations with financial advisors can help determine your appropriate risk profile.