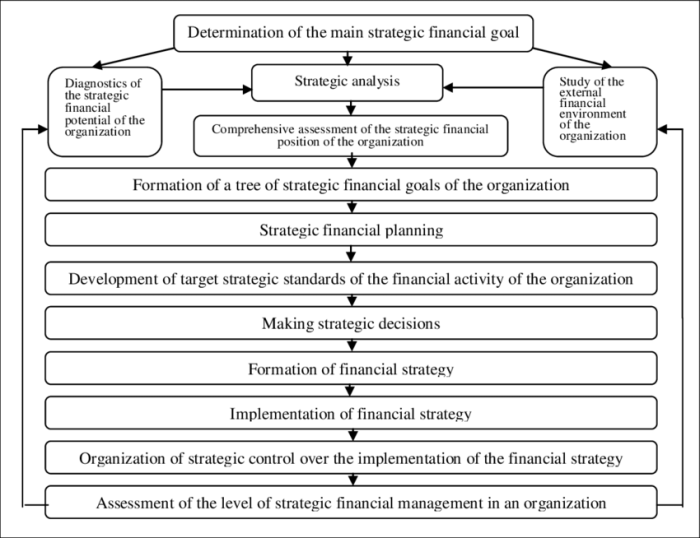

Mastering strategic financial management is crucial for any business aiming for sustainable growth and profitability. This involves a multifaceted approach encompassing forecasting, budgeting, capital allocation, risk mitigation, and performance evaluation. Effective strategies in these areas are not merely about numbers; they represent the bedrock of informed decision-making, ensuring the long-term health and success of the enterprise.

This exploration delves into key techniques, providing practical examples and frameworks to navigate the complexities of financial planning and control. From optimizing working capital to making informed investment decisions, we will cover essential elements to empower businesses to achieve their financial objectives.

Financial Forecasting and Budgeting

Financial forecasting and budgeting are crucial for the success of any medium-sized business. A well-structured forecast provides a roadmap for future operations, enabling proactive decision-making and resource allocation. Effective budgeting, in turn, ensures that the business stays on track to achieve its financial goals. These processes are intrinsically linked, with the forecast informing the budget and the budget guiding operational activities.

Developing a Comprehensive Financial Forecast

Developing a comprehensive financial forecast involves a multi-step process. First, historical financial data is analyzed to identify trends and patterns in revenue, expenses, and cash flow. This analysis forms the basis for projecting future performance. Next, key assumptions are established regarding market conditions, economic growth, and internal factors such as sales growth rates and pricing strategies. For example, a medium-sized clothing retailer might assume a 5% increase in sales based on past performance and projected market growth, and a 2% increase in raw material costs due to inflation. These assumptions are crucial, and their accuracy directly impacts the forecast’s reliability. Sensitivity analysis, exploring different scenarios based on varying assumptions (e.g., optimistic, pessimistic, and most likely), is often conducted to assess the forecast’s robustness. Potential challenges include unforeseen economic downturns, changes in consumer behavior, and inaccurate sales projections. The forecast should be regularly reviewed and updated to reflect changing circumstances.

Budgeting Methods and Suitability

Several budgeting methods exist, each with its strengths and weaknesses. Zero-based budgeting starts from scratch each year, requiring justification for every expenditure. This approach can be time-consuming but promotes efficiency by eliminating unnecessary spending. Incremental budgeting, on the other hand, uses the previous year’s budget as a base and adjusts it based on anticipated changes. This method is simpler and faster but may perpetuate inefficiencies. Activity-based budgeting allocates resources based on specific activities and their expected costs. This approach is particularly useful for businesses with complex operations and multiple projects. The choice of budgeting method depends on the business’s size, complexity, and industry. A small, stable business might find incremental budgeting sufficient, while a rapidly growing company with multiple product lines might benefit from activity-based budgeting. Zero-based budgeting is often suitable for organizations seeking significant cost reductions.

Sample Budget

The following table presents a sample budget incorporating both operating and capital expenditures for a fictional medium-sized bakery for the fiscal year 2024. Note that this is a simplified example and a real-world budget would be far more detailed.

| Revenue | Expenses | Assets | Liabilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| $500,000 (Sales) | $300,000 (Cost of Goods Sold) | $100,000 (Cash) | $50,000 (Loans Payable) |

| $50,000 (Salaries) | $200,000 (Equipment) | $20,000 (Accounts Payable) | |

| $20,000 (Rent) | $50,000 (Inventory) | ||

| $30,000 (Marketing) | |||

| $10,000 (Utilities) | |||

| Total: $500,000 | Total: $410,000 | Total: $350,000 | Total: $70,000 |

Working Capital Management

Effective working capital management is crucial for a company’s financial health and operational efficiency. It involves the strategic management of current assets (cash, accounts receivable, and inventory) and current liabilities (accounts payable, short-term debt) to ensure the smooth functioning of daily operations while maximizing profitability. Optimizing working capital allows businesses to meet their short-term obligations, invest in growth opportunities, and weather unexpected economic downturns.

Working capital management directly impacts a company’s liquidity, profitability, and overall financial stability. Insufficient working capital can lead to missed payment deadlines, lost sales opportunities, and even bankruptcy. Conversely, efficient working capital management allows for a healthy cash flow, enabling strategic investments and enhancing the company’s resilience against economic shocks. Understanding and effectively managing the components of working capital is therefore a cornerstone of successful financial management.

Accounts Receivable and Payable Management Best Practices

Optimizing accounts receivable and payable is key to improving cash flow. Effective strategies involve minimizing the time it takes to collect payments from customers while strategically extending payment terms to suppliers. This delicate balance requires careful planning and monitoring. For accounts receivable, proactive credit checks, efficient invoicing processes, and prompt follow-up on overdue payments are crucial. For accounts payable, negotiating favorable payment terms with suppliers and taking advantage of early payment discounts can significantly improve cash flow. Regularly reviewing aging reports for both receivables and payables provides valuable insights into payment trends and helps identify potential problems early on. For example, a company might implement a system of automated reminders for overdue invoices or offer discounts to customers who pay early. Similarly, negotiating longer payment terms with reliable suppliers can free up cash for other business needs.

Implications of Insufficient Working Capital and Mitigation Strategies

Insufficient working capital can severely hamper a company’s operations. A lack of readily available cash can lead to missed payments to suppliers, resulting in damaged relationships and potential supply disruptions. It can also limit a company’s ability to invest in growth opportunities, such as new equipment or marketing campaigns. Furthermore, insufficient working capital can make it difficult to meet payroll obligations, leading to employee dissatisfaction and potential legal issues. To mitigate these risks, companies should regularly monitor their working capital levels and develop contingency plans. This might involve securing a line of credit or establishing a revolving credit facility to access funds quickly when needed. Regular cash flow forecasting can also help anticipate potential shortfalls and allow for proactive adjustments. For instance, a small business experiencing seasonal fluctuations in sales might secure a short-term loan during slower periods to cover operating expenses.

Improving Inventory Management and Reducing Carrying Costs

Effective inventory management is vital for minimizing carrying costs (storage, insurance, obsolescence) while ensuring sufficient stock to meet customer demand. A well-executed plan can significantly improve profitability.

- Implement a robust inventory tracking system: This allows for real-time monitoring of stock levels, facilitating timely replenishment and preventing stockouts or overstocking.

- Optimize ordering quantities: Utilizing techniques like Economic Order Quantity (EOQ) calculations helps determine the optimal order size to minimize total inventory costs.

- Improve forecasting accuracy: Employing advanced forecasting methods, such as time series analysis or machine learning, leads to more accurate demand predictions, reducing the risk of overstocking or stockouts.

- Regularly review inventory levels: Conducting periodic inventory audits and analyzing slow-moving or obsolete items helps identify areas for improvement and potential write-offs.

- Implement a just-in-time (JIT) inventory system: Where feasible, adopting a JIT system minimizes inventory holding costs by receiving materials only when needed for production.

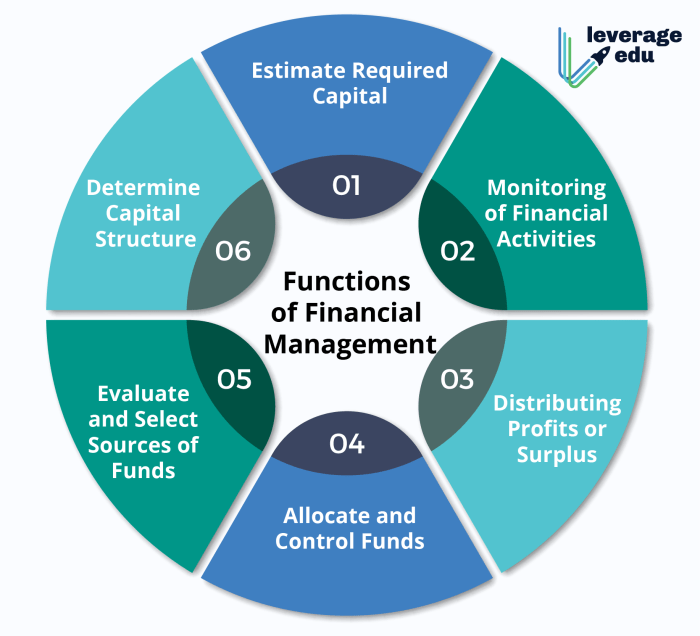

Capital Structure Decisions

A firm’s capital structure represents the mix of debt and equity financing used to fund its operations and growth. Choosing the right balance is crucial, as it significantly impacts a company’s financial risk and potential return. Understanding the trade-offs between debt and equity is essential for maximizing shareholder value.

Debt Financing versus Equity Financing

Debt financing involves borrowing money, typically through loans or bonds, which must be repaid with interest. Equity financing, conversely, involves selling ownership stakes in the company, typically through issuing stock. Both methods have distinct advantages and disadvantages concerning financial risk and return. Debt financing offers tax benefits due to interest being a tax-deductible expense, potentially leading to higher returns for shareholders. However, it increases financial leverage, making the company more vulnerable to financial distress if earnings decline. Equity financing dilutes ownership but reduces financial risk as there’s no mandatory repayment schedule. The choice depends on factors like the company’s risk tolerance, growth prospects, and access to capital markets.

Factors Influencing Optimal Capital Structure

Several factors influence a company’s optimal capital structure, which is the mix of debt and equity that minimizes the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) and maximizes firm value. These factors include the company’s size, profitability, growth rate, industry characteristics, tax rates, and access to capital markets. For instance, a stable, mature company with consistent cash flows might comfortably leverage a higher debt ratio compared to a rapidly growing tech startup with unpredictable earnings. Similarly, companies operating in industries with high fixed costs might find it challenging to maintain high debt levels. Tax rates play a crucial role, as interest payments on debt are tax-deductible, making debt financing more attractive in high-tax environments.

Hypothetical Scenario: Capital Structure and Profitability

Let’s consider a hypothetical scenario for “XYZ Corp,” a manufacturing company. We’ll analyze the impact of different capital structures on its profitability and financial risk. We’ll assume a constant level of operating income for simplicity.

| Scenario | Debt Ratio | Return on Equity (ROE) | Financial Risk (Qualitative) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1: Low Debt | 20% | 15% | Low |

| Scenario 2: Moderate Debt | 40% | 20% | Moderate |

| Scenario 3: High Debt | 60% | 25% | High |

| Scenario 4: All Equity | 0% | 10% | Very Low |

This table illustrates how increasing the debt ratio initially boosts ROE due to financial leverage. However, it also significantly increases financial risk. Scenario 4, with all-equity financing, shows the lowest ROE but also the lowest risk. The optimal capital structure for XYZ Corp would likely lie between Scenario 2 and Scenario 3, balancing the higher return with acceptable risk. The exact optimal point would depend on management’s risk tolerance and the prevailing market conditions.

Investment Appraisal Techniques

Investment appraisal techniques are crucial tools for businesses to evaluate the profitability and viability of potential projects. By systematically assessing the financial implications of an investment, companies can make informed decisions that align with their strategic objectives and maximize shareholder value. This section will explore three common methods: Net Present Value (NPV), Internal Rate of Return (IRR), and Payback Period, highlighting their strengths and weaknesses through a practical example.

Net Present Value (NPV)

Net Present Value calculates the difference between the present value of cash inflows and the present value of cash outflows over a period of time. A positive NPV indicates that the project is expected to generate more value than it costs, making it a worthwhile investment. Conversely, a negative NPV suggests the project is likely to result in a net loss. The method explicitly considers the time value of money, a critical factor in long-term investment decisions.

Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

The Internal Rate of Return represents the discount rate that makes the Net Present Value of a project equal to zero. In simpler terms, it’s the rate of return the project is expected to generate. A higher IRR generally indicates a more attractive investment opportunity. However, IRR can be less straightforward to interpret than NPV, particularly when dealing with multiple cash flows or non-conventional cash flows (where there are changes in the sign of the cash flows).

Payback Period

The Payback Period method determines the length of time it takes for an investment to generate enough cash inflows to recover its initial cost. It’s a simple and easily understood method, particularly useful for assessing the liquidity risk of a project. However, it doesn’t consider the time value of money and ignores cash flows beyond the payback period, potentially overlooking long-term profitability.

Hypothetical Investment Project and Appraisal

Let’s consider a hypothetical project with an initial investment of $100,000 and the following projected cash inflows over five years: Year 1: $25,000; Year 2: $30,000; Year 3: $35,000; Year 4: $40,000; Year 5: $40,000. We will assume a discount rate of 10% for NPV calculations.

| Method | Calculation | Result | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Net Present Value (NPV) | PV of cash inflows – Initial Investment = ($25,000/1.1) + ($30,000/1.1²) + ($35,000/1.1³) + ($40,000/1.1⁴) + ($40,000/1.1⁵) – $100,000 | $22,727.27 (approximately) | Positive NPV indicates the project is expected to generate a net profit. |

| Internal Rate of Return (IRR) | The discount rate at which NPV = 0 (requires iterative calculation or financial calculator/software) | 22% (approximately) | IRR exceeds the discount rate (10%), suggesting a profitable investment. |

| Payback Period | Cumulative cash inflows until initial investment is recovered | 3 years (approximately) | The initial investment is recovered within 3 years. |

Risk Management and Control

Effective risk management is crucial for the long-term success and sustainability of any business. Ignoring potential risks can lead to significant financial losses, reputational damage, and even business failure. A robust risk management framework allows businesses to proactively identify, assess, and mitigate potential threats, ultimately enhancing profitability and stability.

Types of Financial Risks and Their Impact

Financial risks encompass a wide range of potential threats that can negatively affect a company’s financial performance. Understanding these risks and their potential impact is the first step towards effective mitigation. Three primary categories of financial risk are market risk, credit risk, and operational risk. Each presents unique challenges and necessitates specific strategies for management.

Market Risk and Mitigation Strategies

Market risk refers to the potential for losses stemming from fluctuations in market conditions, such as interest rates, exchange rates, and commodity prices. For example, a company heavily reliant on exports might suffer significant losses if the value of its domestic currency appreciates sharply against the currencies of its trading partners. Mitigation strategies include hedging techniques, such as using derivatives (like futures and options contracts) to lock in favorable exchange rates or interest rates, and diversifying operations geographically or across product lines to reduce dependence on any single market. Diversification across asset classes can also help reduce overall portfolio risk.

Credit Risk and Mitigation Strategies

Credit risk represents the possibility of losses due to a borrower’s failure to repay a debt. This risk is particularly relevant for businesses that extend credit to customers or rely on financing from lenders. A bank, for instance, faces credit risk when it lends money to businesses or individuals; if a borrower defaults, the bank loses the principal and may incur additional costs in attempting to recover the debt. Effective credit risk mitigation involves thorough credit checks, setting appropriate credit limits, requiring collateral, and diversifying the lending portfolio to avoid overexposure to any single borrower or industry. Credit insurance can also be used to transfer some of the credit risk to an insurance company.

Operational Risk and Mitigation Strategies

Operational risk encompasses the potential for losses arising from inadequate or failed internal processes, people, and systems, or from external events. This includes risks associated with fraud, technology failures, natural disasters, and human error. For example, a cyberattack that disrupts a company’s operations could lead to significant financial losses, reputational damage, and legal liabilities. Mitigation strategies for operational risk focus on improving internal controls, investing in robust technology infrastructure, implementing business continuity plans, and providing thorough employee training. Insurance policies can also help cover potential losses from certain operational risks.

A Risk Management Framework

A comprehensive risk management framework should integrate both qualitative and quantitative assessment methods to provide a holistic view of the organization’s risk profile. The framework should be dynamic, regularly reviewed, and adapted to reflect changes in the business environment.

- Risk Identification: A systematic process to identify all potential financial risks facing the organization, using brainstorming sessions, scenario planning, and checklists. This phase aims for a comprehensive list of all conceivable risks.

- Qualitative Risk Assessment: Assessing the likelihood and impact of each identified risk using subjective judgment and expert opinions. This involves ranking risks based on their potential severity and probability of occurrence. A simple matrix can be used to visually represent this assessment.

- Quantitative Risk Assessment: Employing statistical methods and financial models to estimate the potential financial impact of identified risks. This might involve using Monte Carlo simulations to model the probability distribution of potential losses under different scenarios. This provides numerical estimates of risk.

- Risk Response Planning: Developing strategies to address each identified risk. Options include risk avoidance, risk reduction (mitigation), risk transfer (insurance), and risk acceptance. The choice of response will depend on the risk’s likelihood and impact.

- Risk Monitoring and Reporting: Regularly monitoring the effectiveness of risk management strategies and reporting on key risk indicators (KRIs) to senior management. This allows for timely adjustments to the risk management plan as needed.

Performance Evaluation and Control

Effective performance evaluation and control are crucial for ensuring a company’s strategic goals are met. By regularly monitoring key financial metrics and comparing actual results against planned targets, businesses can identify areas of strength and weakness, make necessary adjustments, and ultimately improve profitability and efficiency. This involves utilizing a range of financial ratios, conducting variance analysis, and visualizing key performance indicators (KPIs) through dashboards.

Key Financial Ratios for Performance Assessment

Financial ratios provide a standardized way to assess a company’s performance across various dimensions. Analyzing these ratios allows for both internal benchmarking (comparing performance over time) and external benchmarking (comparing performance against industry competitors). The most important ratios fall into three categories: profitability, liquidity, and solvency.

- Profitability Ratios: These ratios indicate a company’s ability to generate profits from its operations. Examples include Gross Profit Margin (Gross Profit / Revenue), Net Profit Margin (Net Profit / Revenue), Return on Assets (Net Profit / Total Assets), and Return on Equity (Net Profit / Shareholders’ Equity). A high gross profit margin suggests efficient cost control in production, while a high net profit margin indicates strong overall profitability after all expenses are considered. Return on assets and equity measure how effectively the company uses its assets and equity to generate profits.

- Liquidity Ratios: These ratios measure a company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations. Key liquidity ratios include Current Ratio (Current Assets / Current Liabilities) and Quick Ratio ((Current Assets – Inventory) / Current Liabilities). A current ratio above 1 generally indicates sufficient liquidity, while the quick ratio provides a more conservative measure by excluding inventory, which may not be easily converted to cash. A low liquidity ratio may suggest a higher risk of default on short-term debt.

- Solvency Ratios: These ratios assess a company’s ability to meet its long-term obligations. Important solvency ratios include Debt-to-Equity Ratio (Total Debt / Shareholders’ Equity) and Times Interest Earned (Earnings Before Interest and Taxes (EBIT) / Interest Expense). A high debt-to-equity ratio suggests a higher reliance on debt financing, potentially increasing financial risk. The times interest earned ratio indicates the company’s ability to cover its interest payments from its operating income. A low ratio may signal potential difficulties in servicing debt.

Variance Analysis for Performance Monitoring

Variance analysis compares budgeted or planned performance with actual results. This process identifies deviations and helps pinpoint the underlying causes. Variances can be favorable (positive) or unfavorable (negative), depending on whether the actual result exceeds or falls short of the budget. For example, a favorable sales variance might be due to increased demand, while an unfavorable cost variance could result from unexpected price increases or production inefficiencies.

Variance = Actual Result – Budgeted Result

Analyzing variances requires investigation into the root causes. For instance, a significant unfavorable variance in direct materials cost might be due to higher raw material prices, increased waste, or changes in supplier contracts. Identifying these causes enables corrective actions to be taken to improve future performance.

Sample Performance Dashboard

A performance dashboard provides a visual overview of key financial metrics. Consider a dashboard with three sections: Profitability, Liquidity, and Solvency.

The dashboard uses a color-coded system: green for positive performance (above target), yellow for near-target performance, and red for under-performance (below target). Each metric is represented by a gauge or bar chart, accompanied by a relevant icon (e.g., a dollar sign for profit margin, a water droplet for liquidity, a scale for solvency).

The layout is clear and concise, with each section clearly labeled. For example, the Profitability section might display Net Profit Margin, Gross Profit Margin, and Return on Equity, each represented by a gauge with a needle indicating the current value and the target range highlighted in green, yellow, and red segments. The Liquidity section might include Current Ratio and Quick Ratio, represented as bar charts with the target range highlighted. The Solvency section could show Debt-to-Equity Ratio and Times Interest Earned, again using bar charts or gauges. This visual representation allows for quick identification of areas requiring attention and facilitates effective decision-making. For instance, a red gauge for Net Profit Margin would immediately highlight a need for investigation into profitability issues.

Financial Statement Analysis

Financial statement analysis is a crucial aspect of strategic financial management. It involves examining a company’s balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement to understand its financial health, performance, and prospects. By analyzing these statements, stakeholders can make informed decisions regarding investment, lending, and overall business strategy. This analysis provides insights into profitability, liquidity, solvency, and efficiency.

Interpreting Financial Statements

The balance sheet provides a snapshot of a company’s assets, liabilities, and equity at a specific point in time. The income statement summarizes a company’s revenues, expenses, and profits over a period. The cash flow statement tracks the movement of cash both into and out of the company during a specific period. Understanding the interrelationships between these three statements is vital for a comprehensive analysis. For example, a high level of accounts receivable on the balance sheet might indicate slow collections, which could impact the cash flow statement and ultimately affect profitability as shown on the income statement.

Identifying Trends and Anomalies

Analyzing financial statements over multiple periods allows for the identification of trends and anomalies. This involves comparing key ratios and metrics across different years to pinpoint significant changes in performance. For example, a consistent decline in gross profit margin might suggest issues with pricing strategies or rising input costs. Anomalies, such as a sudden surge in accounts payable, warrant further investigation to determine the underlying cause. Techniques such as trend analysis, common-size statements, and ratio analysis are commonly employed to identify these patterns. For instance, a consistently increasing current ratio could indicate improved liquidity, while a decreasing quick ratio might signal potential short-term liquidity issues.

A Step-by-Step Guide to Financial Statement Analysis

A thorough financial statement analysis requires a systematic approach. The following steps provide a framework for conducting a comprehensive analysis:

- Gather Data: Collect the company’s balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement for at least three to five years. This allows for trend analysis and identification of anomalies.

- Calculate Key Ratios: Compute relevant financial ratios such as profitability ratios (gross profit margin, net profit margin, return on assets), liquidity ratios (current ratio, quick ratio), solvency ratios (debt-to-equity ratio, times interest earned), and efficiency ratios (inventory turnover, accounts receivable turnover). These ratios provide insights into different aspects of the company’s financial performance.

- Conduct Trend Analysis: Analyze the trends in key ratios and metrics over time. Look for significant changes or deviations from the established patterns. For example, a consistent decline in the current ratio could indicate deteriorating liquidity.

- Compare to Industry Benchmarks: Compare the company’s financial ratios to those of its competitors and industry averages. This provides context and helps to assess the company’s relative performance. Deviation from industry norms may warrant further investigation.

- Analyze Cash Flow: Examine the cash flow statement to assess the company’s ability to generate cash from operations, investing activities, and financing activities. A strong cash flow from operations is a positive indicator of financial health.

- Assess Financial Health: Based on the analysis of the ratios, trends, and cash flow, assess the overall financial health of the company. Consider factors such as profitability, liquidity, solvency, and efficiency.

- Identify Potential Problems and Opportunities: Based on the analysis, identify potential problems and opportunities for the company. For example, a high debt-to-equity ratio might suggest excessive reliance on debt financing, while a low inventory turnover could indicate inefficient inventory management.

Summary

In conclusion, strategic financial management is a dynamic process demanding continuous adaptation and refinement. By integrating forecasting, budgeting, capital structure optimization, and robust risk management practices, businesses can build a strong financial foundation. This proactive approach enables informed decision-making, optimized resource allocation, and ultimately, sustainable growth and long-term prosperity.

Questions and Answers

What is the difference between a budget and a forecast?

A budget is a detailed plan of anticipated revenues and expenditures for a specific period, often used for internal control. A forecast is a projection of future financial performance, often based on various scenarios and market trends, used for strategic planning.

How can I improve my company’s cash flow?

Improve cash flow by optimizing accounts receivable (faster collection), managing accounts payable (negotiate favorable payment terms), and controlling inventory levels (reduce storage costs and minimize obsolescence).

What are some common financial ratios used in performance evaluation?

Common ratios include liquidity ratios (current ratio, quick ratio), profitability ratios (gross profit margin, net profit margin), and solvency ratios (debt-to-equity ratio, times interest earned).

How do I choose the right capital structure for my business?

The optimal capital structure balances the benefits of debt financing (leverage) with the risks of higher financial leverage. Consider factors such as cost of debt, tax implications, and the company’s risk tolerance.