Ratio Analysis Interpretation Guide: Unlocking the secrets hidden within financial statements! This guide dives deep into the fascinating world of ratio analysis, transforming complex numbers into insightful narratives about a company’s financial health. We’ll explore various ratio categories – from liquidity, a measure of short-term solvency, to profitability, the lifeblood of any business – and equip you with the tools to interpret the data like a seasoned financial analyst. Get ready to decipher the language of finance and make informed decisions based on solid, data-driven insights.

We’ll cover the essential ratios, their calculations, and most importantly, what they *really* mean. We’ll also explore the art of comparing ratios across industries and over time, highlighting the pitfalls to avoid and the best practices to embrace. By the end, you’ll be able to confidently analyze financial statements, identify potential risks and opportunities, and impress even the most seasoned investors (or at least, your accounting professor).

Introduction to Ratio Analysis

Ratio analysis, my friends, is the financial equivalent of a detective’s magnifying glass. It allows us to peer into the heart of a company’s financial statements, unearthing hidden truths and revealing the secrets behind the numbers. Instead of just staring blankly at a balance sheet, we can use ratios to transform those dry figures into a compelling narrative of a company’s performance, liquidity, and overall financial health. Think of it as financial statement CSI, but (hopefully) with less blood and more spreadsheets.

Ratio analysis is the process of calculating and interpreting financial ratios derived from a company’s financial statements (balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement). Its purpose is to assess a company’s financial performance, liquidity, solvency, and efficiency, providing valuable insights for decision-making by investors, creditors, and management. It helps paint a clearer picture than just looking at raw numbers.

Types of Financial Ratios

Financial ratios are broadly categorized into four key types, each offering a unique perspective on a company’s financial standing. These categories are not mutually exclusive; understanding the interplay between them provides the most complete picture. Think of them as different lenses on the same financial microscope.

Liquidity Ratios

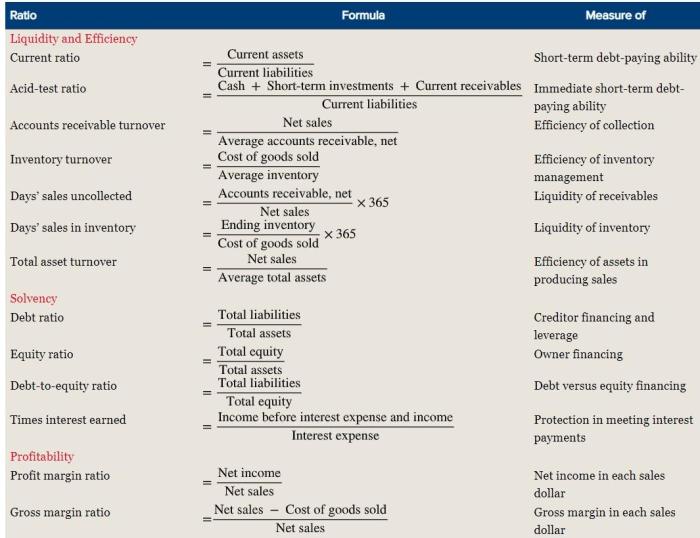

Liquidity ratios gauge a company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations. These ratios are crucial for assessing the immediate financial health of a business. A company with strong liquidity can easily pay its bills as they come due, while a company with weak liquidity might face financial distress. Key examples include the Current Ratio (Current Assets / Current Liabilities) and the Quick Ratio ((Current Assets – Inventory) / Current Liabilities). A high current ratio suggests strong liquidity, but an excessively high ratio might indicate inefficient asset management.

Solvency Ratios

Solvency ratios, on the other hand, focus on a company’s long-term financial stability. These ratios help determine a company’s ability to meet its long-term debt obligations. They provide a more comprehensive picture of a company’s ability to survive over the long haul. Examples include the Debt-to-Equity Ratio (Total Debt / Total Equity) and the Times Interest Earned Ratio (EBIT / Interest Expense). A high debt-to-equity ratio suggests a higher level of financial risk.

Profitability Ratios

Profitability ratios measure a company’s ability to generate profits from its operations. These ratios are vital for assessing the efficiency and effectiveness of a company’s business model. They show whether the company is making money and how efficiently it is doing so. Key examples include Gross Profit Margin (Gross Profit / Revenue), Net Profit Margin (Net Income / Revenue), and Return on Equity (Net Income / Shareholder Equity). A high net profit margin indicates a company is generating a significant profit for each dollar of revenue.

Efficiency Ratios

Efficiency ratios, also known as activity ratios, evaluate how effectively a company manages its assets and liabilities. These ratios reveal how well a company is utilizing its resources to generate sales and profits. Key examples include Inventory Turnover (Cost of Goods Sold / Average Inventory) and Asset Turnover (Revenue / Average Total Assets). A high inventory turnover suggests efficient inventory management, while a low turnover might indicate obsolete or slow-moving inventory.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Ratio Analysis

| Ratio Type | Strengths | Weaknesses | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquidity | Provides a quick assessment of short-term financial health; easy to calculate. | Can be misleading if inventory is difficult to liquidate; doesn’t consider future cash flows. | Compare ratios to industry benchmarks and historical trends. |

| Solvency | Indicates long-term financial stability; useful for evaluating creditworthiness. | Doesn’t account for off-balance sheet financing; can be complex to interpret. | Consider the company’s capital structure and industry norms. |

| Profitability | Shows how effectively a company generates profits; useful for comparing companies. | Can be affected by accounting methods; doesn’t reflect cash flows. | Analyze trends over time and compare to competitors. |

| Efficiency | Highlights how effectively assets are utilized; identifies areas for improvement. | Can be influenced by seasonal factors; requires detailed understanding of the business. | Consider industry-specific benchmarks and operational factors. |

Importance of Ratio Analysis in Business Decisions

Ratio analysis is not merely an academic exercise; it’s a crucial tool for informed business decision-making. Investors use it to evaluate investment opportunities, creditors assess creditworthiness, and management identifies areas for improvement. By comparing ratios across time and against industry benchmarks, businesses can identify strengths and weaknesses, track progress, and make strategic decisions to improve financial performance. It’s the financial equivalent of a well-tuned engine, allowing for smoother operation and better performance. Without it, you’re basically driving blind.

Liquidity Ratios

Assessing a company’s liquidity – its ability to meet its short-term obligations – is like judging a tightrope walker: a slight wobble can be disastrous. Liquidity ratios provide crucial insights into this precarious balancing act, revealing whether a company is swimming in cash or teetering on the brink of insolvency. Understanding these ratios is essential for investors, creditors, and the company itself to make informed decisions.

Liquidity ratios are a family of financial metrics that help determine a company’s ability to pay off its short-term debts. They provide a snapshot of a company’s immediate financial health, allowing stakeholders to assess the risk associated with its short-term obligations. These ratios, while seemingly simple, can be surprisingly insightful and offer a window into the inner workings of a company’s cash flow. Let’s delve into the fascinating world of liquidity analysis!

Current Ratio

The current ratio is the most basic liquidity ratio, calculated by dividing current assets by current liabilities. It essentially shows the proportion of a company’s short-term assets available to cover its short-term debts. A higher current ratio generally suggests better liquidity. For example, a company with a current ratio of 2.0 has twice as many current assets as current liabilities. This implies a greater capacity to meet its short-term obligations. However, an excessively high ratio might indicate inefficient use of assets. Imagine a company hoarding cash instead of investing it profitably; that’s not exactly a recipe for success, is it?

Quick Ratio

The quick ratio, also known as the acid-test ratio, is a more stringent measure of liquidity. It excludes inventories from current assets, as inventories can be less liquid than other current assets (imagine trying to sell a mountain of unsold fidget spinners!). The formula is (Current Assets – Inventories) / Current Liabilities. The quick ratio provides a more conservative assessment of a company’s ability to meet its immediate obligations, as it focuses on the most readily convertible assets. A company with a healthy quick ratio is less likely to face a cash crunch.

Cash Ratio

The cash ratio takes the most conservative approach, focusing solely on the most liquid assets: cash and cash equivalents. It’s calculated by dividing (Cash + Cash Equivalents) by Current Liabilities. This ratio offers the most immediate and direct measure of a company’s ability to pay its bills. It’s the ultimate test of a company’s immediate solvency. Think of it as the financial equivalent of a quick-draw contest – the faster the company can access cash, the better its chances of survival.

Comparison of Liquidity Ratios

The three ratios – current, quick, and cash – offer a tiered assessment of liquidity, each providing a different perspective. The current ratio provides the broadest view, while the quick ratio offers a more conservative view by excluding less liquid inventories. The cash ratio provides the most stringent measure, focusing only on the most readily available assets. The choice of which ratio to use depends on the specific context and the level of conservatism desired. For example, a bank might place more emphasis on the cash ratio, while a retailer might focus on the current ratio, considering inventory turnover.

Industries Where Specific Liquidity Ratios Are Critical

Certain industries inherently rely more heavily on specific liquidity ratios. For example, in the manufacturing sector, the current ratio is crucial because of significant inventory holdings. Conversely, companies in the service industry, with minimal inventory, might place greater emphasis on the quick ratio or cash ratio. Financial institutions, with their high reliance on readily available cash, naturally pay close attention to the cash ratio. The importance of each ratio is dictated by the industry’s unique characteristics and operational dynamics.

Potential Issues Indicated by Unusually High or Low Liquidity Ratios

Extreme values for liquidity ratios, whether high or low, can signal underlying issues.

- Unusually High Liquidity Ratios: This could indicate inefficient asset management, excessive cash holdings, or impending financial distress (ironically!). The company might be hoarding cash for a future acquisition, but it could also be a sign that they are anticipating future losses.

- Unusually Low Liquidity Ratios: This suggests a significant risk of short-term financial distress. The company might struggle to meet its immediate obligations, potentially leading to default on loans or bankruptcy. This scenario screams “financial trouble!”

Solvency Ratios

Solvency ratios, unlike their liquidity-obsessed cousins, are less concerned with whether a company can pay its bills *right now* and more interested in its long-term survival. Think of them as the financial equivalent of a robust pension plan – vital for a comfortable retirement (or, in this case, continued business operation). They assess a company’s ability to meet its long-term debt obligations, providing a glimpse into its financial health beyond the immediate horizon. A healthy dose of solvency is crucial; otherwise, you’re looking at a potential financial shipwreck.

Debt-to-Equity Ratio

This ratio compares a company’s total debt to its total equity. It’s a fundamental measure of financial leverage, revealing how much a company relies on borrowed money versus owner’s investment. A high debt-to-equity ratio indicates a greater reliance on debt financing, which can amplify both profits and losses. Conversely, a low ratio suggests a more conservative financial approach, relying less on borrowed funds. For example, a company with a debt-to-equity ratio of 2.0 means it has twice as much debt as equity. This might be perfectly acceptable for a rapidly growing tech startup, but alarming for a mature utility company. The “acceptable” level varies significantly depending on the industry and the company’s specific circumstances.

Debt-to-Equity Ratio = Total Debt / Total Equity

Times Interest Earned

This ratio measures a company’s ability to meet its interest payments on debt. It’s calculated by dividing earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) by total interest expense. A high times interest earned ratio signifies a comfortable ability to cover interest payments, while a low ratio suggests potential difficulties in meeting these obligations. For instance, a ratio of 5 indicates that the company’s earnings are five times greater than its interest expense, providing a substantial cushion. A ratio below 1, however, is a major red flag, suggesting the company may struggle to pay its interest, potentially leading to financial distress.

Times Interest Earned = Earnings Before Interest and Taxes (EBIT) / Interest Expense

Debt Service Coverage Ratio

This ratio is a more comprehensive measure of a company’s ability to service its debt, including both interest and principal payments. It considers the company’s cash flow from operations relative to its total debt service obligations. A high debt service coverage ratio indicates a strong capacity to meet debt payments, suggesting greater financial stability. A low ratio, on the other hand, raises concerns about the company’s ability to manage its debt effectively. Imagine a company with a ratio of 1.2; it’s barely covering its debt service obligations, leaving little room for error.

Debt Service Coverage Ratio = (Net Operating Income + Non-Cash Charges) / Total Debt Service

Solvency Ratio Summary Table

| Ratio | Calculation | High Value Implication | Low Value Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Debt-to-Equity Ratio | Total Debt / Total Equity | High reliance on debt financing; increased financial risk. | Conservative financing; lower financial risk. |

| Times Interest Earned | EBIT / Interest Expense | Strong ability to cover interest payments. | Potential difficulty in meeting interest obligations. |

| Debt Service Coverage Ratio | (Net Operating Income + Non-Cash Charges) / Total Debt Service | Strong capacity to meet debt payments. | Potential difficulty in managing debt effectively. |

Profitability Ratios

Profitability ratios, the unsung heroes of financial analysis, reveal the true earning power of a company. Unlike their liquidity and solvency brethren, these ratios focus less on *how* a company manages its assets and more on *what* it ultimately achieves – profit! Think of them as the ultimate performance review for a business, highlighting its efficiency and success in generating returns. We’ll delve into the key players in this profitability drama: gross profit margin, operating profit margin, net profit margin, and return on equity.

Gross Profit Margin

The gross profit margin reveals the profitability of a company’s core operations after accounting for the direct costs of producing its goods or services. It’s calculated by subtracting the cost of goods sold (COGS) from revenue, then dividing the result by revenue. In simpler terms, it shows how much money is left over after paying for the things directly involved in making or selling your product.

Gross Profit Margin = (Revenue – Cost of Goods Sold) / Revenue

A higher gross profit margin generally indicates greater efficiency in production or pricing power. For example, a company with a gross profit margin of 60% is keeping more of each sales dollar than one with a margin of 30%. However, it’s crucial to compare this ratio to industry benchmarks and the company’s historical performance to understand its true significance.

Operating Profit Margin

Operating profit margin takes the gross profit margin a step further, showing profitability after considering all operating expenses, such as administrative costs, marketing, and research & development. This provides a more comprehensive view of a company’s operational efficiency, excluding the impact of financing and taxes.

Operating Profit Margin = Operating Income / Revenue

A company with a high operating profit margin suggests strong control over its operating expenses and efficient management of its core business. Imagine two companies with the same revenue; the one with the higher operating profit margin is more adept at managing its day-to-day costs.

Net Profit Margin

The net profit margin is the ultimate measure of profitability, showing the percentage of revenue that translates into net profit after all expenses, including interest and taxes, are deducted. This is the bottom line – the money that actually ends up in the company’s pockets.

Net Profit Margin = Net Income / Revenue

A high net profit margin indicates superior overall efficiency and profitability. However, it’s important to note that a high net profit margin doesn’t always mean a company is financially healthy; it could be achieved through aggressive cost-cutting measures that might harm long-term growth.

Return on Equity (ROE)

Return on equity (ROE) measures how effectively a company uses its shareholders’ investment to generate profits. It shows the return generated on the money invested by shareholders.

Return on Equity = Net Income / Shareholder’s Equity

A high ROE signifies efficient use of shareholder funds and strong profitability. However, it’s crucial to consider the industry average and the company’s financial leverage. A high ROE might be artificially inflated by high debt levels, indicating a higher risk.

Comparison of Profitability Ratios

Each profitability ratio offers a unique perspective on a company’s performance. The gross profit margin focuses on the core business, the operating profit margin incorporates operating expenses, the net profit margin considers all expenses, and ROE focuses on the return to shareholders. Analyzing these ratios together provides a more holistic understanding of profitability than using any one ratio in isolation. For instance, a high gross profit margin but low net profit margin might suggest high operating expenses that need attention.

Interpreting Changes in Profitability Ratios Over Time

Analyzing trends in profitability ratios over several years is crucial for understanding a company’s performance trajectory. A consistent increase in these ratios suggests improving profitability, while a decline signals potential problems. For example, a decreasing net profit margin might indicate rising competition or increasing costs. Context is king here; understanding the underlying reasons for changes is essential.

Comparing Companies Within the Same Industry

Profitability ratios are invaluable for comparing companies within the same industry. By comparing ratios across competitors, investors can identify companies with superior profitability and efficiency. However, it’s crucial to consider differences in business models and accounting practices. For instance, comparing a high-volume, low-margin retailer with a niche, high-margin retailer requires careful interpretation of the ratios.

Efficiency Ratios: Ratio Analysis Interpretation Guide

Efficiency ratios, the unsung heroes of financial analysis, reveal the inner workings of a company’s operational prowess. Unlike their more flamboyant cousins, the profitability ratios, efficiency ratios don’t directly measure profit. Instead, they meticulously examine how effectively a company utilizes its assets to generate sales. Think of them as the company’s personal trainers, highlighting areas for improvement and showcasing the effectiveness of the company’s workout routine (i.e., operational strategies). A strong performance in these ratios suggests a lean, mean, profit-making machine.

Inventory Turnover Ratio

The inventory turnover ratio measures how efficiently a company sells its inventory. A higher ratio generally indicates efficient inventory management, minimizing storage costs and the risk of obsolescence. Conversely, a low ratio might suggest slow-moving inventory, potential for losses due to spoilage or outdated products, or perhaps even an overestimation of demand. The formula for calculating this vital statistic is:

Cost of Goods Sold / Average Inventory

. For example, a company with a Cost of Goods Sold of $1,000,000 and average inventory of $200,000 has an inventory turnover ratio of 5. This suggests the company sells its entire inventory five times a year. Factors influencing this ratio include sales forecasting accuracy, production efficiency, and the effectiveness of inventory control systems. Improvements in inventory management, such as implementing a Just-in-Time (JIT) inventory system, can lead to a higher turnover ratio, reducing storage costs and freeing up capital for other investments, ultimately boosting profitability.

Accounts Receivable Turnover Ratio

This ratio assesses how quickly a company collects payments from its customers. A high ratio suggests efficient credit and collection policies, minimizing the risk of bad debts and freeing up cash flow. A low ratio might signal lax credit policies, leading to increased outstanding receivables and potential losses. The formula is:

Net Credit Sales / Average Accounts Receivable

. For instance, a company with net credit sales of $800,000 and average accounts receivable of $100,000 has a ratio of 8, implying they collect their receivables eight times a year. Factors affecting this ratio include credit terms offered to customers, the efficiency of the collection process, and the overall economic climate. Improving credit policies, implementing stricter collection procedures, and offering early payment discounts can all contribute to a higher turnover ratio, leading to improved cash flow and ultimately, higher profitability.

Asset Turnover Ratio

The asset turnover ratio measures how effectively a company utilizes its assets to generate sales. A higher ratio signifies efficient asset utilization, maximizing the return on investment in assets. A low ratio could suggest underutilization of assets, indicating potential for improvement in operational efficiency. The calculation is:

Net Sales / Average Total Assets

. If a company has net sales of $1,500,000 and average total assets of $750,000, the asset turnover ratio is 2, showing that for every dollar of assets, the company generates $2 in sales. Factors impacting this ratio include the company’s industry, capital intensity, and overall operational efficiency. Investing in more efficient equipment, optimizing production processes, and streamlining operations can increase the asset turnover ratio, leading to increased sales and profitability.

The Relationship Between Efficiency Ratios and Overall Financial Performance

A flowchart illustrating this relationship would depict three branches stemming from “Efficiency Ratios,” each leading to a box labeled “Improved Profitability.” The first branch would be “Higher Inventory Turnover,” leading to “Reduced Storage Costs and Increased Cash Flow.” The second branch would be “Higher Accounts Receivable Turnover,” leading to “Improved Cash Flow and Reduced Bad Debts.” The third branch would be “Higher Asset Turnover,” leading to “Increased Sales and Return on Investment.” All three branches ultimately converge on “Improved Profitability,” highlighting the interconnectedness of efficiency ratios and the overall financial health of a company.

Interpreting Ratio Analysis Results

So, you’ve diligently calculated a mountain of ratios – liquidity, solvency, profitability, efficiency; the works! Now comes the fun part: making sense of it all. Think of it as a financial detective story, where the ratios are your clues, and a healthy company is the culprit you’re trying to identify (or exonerate!).

Interpreting ratio analysis isn’t just about looking at individual numbers; it’s about weaving them together to paint a complete picture of a company’s financial health. It’s like assembling a jigsaw puzzle – each piece (ratio) contributes to the overall image (financial health). A single, out-of-whack ratio might just be a rogue puzzle piece, but several ratios telling the same story? That’s a compelling case.

Combining Ratio Analysis Findings

A holistic understanding emerges when we compare and contrast various ratios. For example, high profitability ratios might seem fantastic, but coupled with low liquidity ratios, they could indicate a company is struggling to manage its cash flow despite making healthy profits – a classic case of “rich but broke.” Similarly, strong solvency ratios might suggest low risk, but weak efficiency ratios could signal operational inefficiencies that are ultimately unsustainable. The interplay between ratios provides far more insight than analyzing them in isolation. Consider a scenario where a company boasts high return on equity (ROE) but has low inventory turnover. This discrepancy might suggest the company is holding onto excess inventory, which, while contributing to the high ROE, could represent an inefficient use of capital. By considering multiple ratios simultaneously, analysts can identify potential inconsistencies and uncover hidden strengths or weaknesses.

Considering Industry Benchmarks and Historical Trends

Comparing a company’s ratios to industry averages provides crucial context. A seemingly low profit margin might be perfectly acceptable within a highly competitive industry, whereas the same margin might be disastrous in a less competitive one. Think of it as comparing apples to apples (or, more accurately, comparing a company’s financial performance to that of its competitors). Furthermore, tracking a company’s ratios over time reveals trends and potential problems. A steadily declining current ratio, for example, might signal looming liquidity issues long before they become critical. Analyzing historical trends allows for a more nuanced understanding of a company’s performance and provides insights into its long-term sustainability.

Limitations of Ratio Analysis and the Need for Additional Information

Ratio analysis, while powerful, isn’t a magic bullet. It relies heavily on the accuracy of the financial statements it’s based on, and creative accounting practices can distort the picture. Furthermore, ratios are just numbers; they don’t capture the qualitative aspects of a business, such as management quality, employee morale, or the strength of its brand. Therefore, relying solely on ratio analysis can be misleading. Always consider additional information, such as industry reports, economic forecasts, and qualitative assessments of the company’s operations and management. Remember, ratios are a tool, not a crystal ball.

Key Considerations for Interpreting Ratio Analysis Findings, Ratio Analysis Interpretation Guide

It’s crucial to approach ratio analysis with a critical eye, considering various factors that can influence the interpretation. Here’s a handy summary:

| Factor | Description | Example | Impact on Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Industry Benchmarks | Comparing ratios to industry averages provides context. | A low profit margin might be acceptable in a highly competitive industry but unacceptable in a less competitive one. | Avoids misinterpreting seemingly low or high ratios. |

| Historical Trends | Analyzing changes in ratios over time reveals trends. | A steadily declining current ratio might signal liquidity problems. | Highlights potential issues before they become critical. |

| Qualitative Factors | Consider factors beyond numbers, such as management quality. | Strong ratios but poor management could lead to future problems. | Provides a more holistic view of the company’s financial health. |

| Economic Conditions | External factors can influence ratio performance. | A recession might impact a company’s profitability regardless of its internal efficiency. | Avoids misinterpreting ratios due to external factors. |

Visualizing Ratio Analysis Data

Let’s face it, staring at a spreadsheet full of ratios is about as exciting as watching paint dry. But fear not, accounting aficionados! We can transform those numbers into compelling visuals that will have your stakeholders clamoring for more. By using charts and graphs, we can breathe life into our ratio analysis and make our findings far more digestible and impactful. Think of it as giving your data a much-needed makeover – from frumpy spreadsheet to dazzling infographic!

Effective presentation of ratio analysis findings relies on choosing the right chart type to highlight specific trends and relationships. Different chart types emphasize different aspects of the data, allowing for a multifaceted understanding of the company’s financial health. A poorly chosen chart can obscure important information, while a well-chosen one can illuminate key insights and even spark a conversation (and who doesn’t love a good accounting conversation?).

Chart Selection for Ratio Analysis

The choice of chart depends heavily on what you want to showcase. For instance, if you want to demonstrate the trend of a single ratio over time, a line chart is your best bet. Want to compare ratios across different periods or companies? Bar charts or column charts are your go-to options. If you’re looking to show the proportion of different components contributing to a total (for example, the breakdown of a company’s revenue streams), then a pie chart might be appropriate. However, overuse of pie charts can lead to visual clutter, so use them judiciously. Remember, clarity and simplicity are key – we want to illuminate, not obfuscate!

Trend Analysis Using Line Charts: Example

Let’s imagine we’re analyzing the Return on Equity (ROE) for “Acme Corporation” over a five-year period. A line chart is ideal for showcasing the trend.

The chart would have “Year” on the horizontal (x) axis, ranging from, say, 2019 to 2023. The vertical (y) axis would represent the “Return on Equity (%)”, ranging from, say, 0% to 25%. Each year would have a data point plotted, representing Acme’s ROE for that year. Let’s assume the following data:

2019: 15%

2020: 18%

2021: 20%

2022: 16%

2023: 22%

The line connecting these points would clearly illustrate the trend. We might observe an upward trend from 2019 to 2021, a slight dip in 2022, and then a recovery in 2023. A clear title, “Acme Corporation Return on Equity (2019-2023),” would complete the picture, making the chart easily understandable and impactful. This visual representation is far more effective than simply listing the numerical data.

Comparative Analysis Using Bar Charts

To compare the profitability of Acme Corporation against its main competitor, “Beta Industries,” we could use a bar chart. The x-axis would list the companies (Acme and Beta), and the y-axis would represent the Net Profit Margin (%). Two bars for each company, one for 2022 and one for 2023, would allow for a direct comparison of their profitability over those two years. This instantly shows which company performed better and how their profitability changed over time. The visual nature of the chart makes the comparison much clearer than a simple table of numbers. A legend would be essential to distinguish Acme’s and Beta’s bars. Again, a descriptive title, such as “Net Profit Margin Comparison: Acme Corp vs. Beta Industries (2022-2023),” would be crucial for clarity.

Summary

Mastering ratio analysis isn’t just about crunching numbers; it’s about understanding the story those numbers tell. This guide has provided you with the framework to interpret financial data, transforming raw figures into a compelling narrative of a company’s financial performance. Remember, while ratios provide valuable insights, they are only one piece of the puzzle. Always consider the broader context, industry trends, and qualitative factors to form a holistic view. So go forth, armed with your newfound knowledge, and conquer the world of financial analysis – one ratio at a time!

FAQ Summary

What happens if a company has a very high current ratio?

A very high current ratio might indicate that the company is holding excessive cash or inventory, which could be inefficient use of assets. It could also suggest a lack of aggressive investment opportunities.

How do I choose which ratios to focus on when analyzing a company?

Prioritize ratios relevant to your specific investment goals and the industry the company operates in. For example, inventory turnover is crucial for retail companies but less so for service-based businesses.

Can ratio analysis predict the future performance of a company?

No, ratio analysis is a snapshot in time. While it provides valuable insights into past and current performance, it cannot definitively predict future outcomes. It’s a tool for informed decision-making, not a crystal ball.

What are some common mistakes to avoid when interpreting ratios?

Avoid comparing ratios across companies with significantly different accounting methods or business models. Also, remember that ratios are just one piece of the puzzle; don’t rely solely on them for investment decisions.