Economic Indicators Explanation Guide: Unlocking the secrets of economic health! This guide delves into the fascinating world of macroeconomic indicators, providing a clear and engaging explanation of key concepts like GDP, inflation, unemployment, and interest rates. We’ll explore how these indicators are calculated, what they tell us about the economy’s performance, and how they influence policy decisions. Get ready to navigate the complexities of economic data with newfound confidence and perhaps even a touch of amusement.

From the intricacies of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) to the subtle shifts in exchange rates, we’ll demystify the often-confusing language of economics. Prepare for a journey through charts, graphs (well, textual representations, for now!), and insightful explanations that will leave you feeling like an economic expert – or at least someone who can confidently discuss the economy at your next cocktail party.

Introduction to Economic Indicators

Navigating the sometimes-bewildering world of economics can feel like trying to assemble IKEA furniture without the instructions – frustrating and potentially leading to a wobbly outcome. Fortunately, we have economic indicators, those handy little data points that offer clues about the overall health and direction of an economy. Understanding these indicators is like getting the IKEA instruction manual – it makes the whole process much clearer and less likely to result in a financial catastrophe.

Economic indicators are essentially statistical measures that reflect the state of the economy. They provide insights into past performance, current conditions, and, crucially, future trends. Think of them as economic crystal balls, though perhaps slightly less prone to shattering. Their purpose is to inform policymakers, businesses, and individuals about economic activity, enabling more informed decision-making. This could range from the government adjusting interest rates to you deciding whether to invest in the stock market or buy a new house. Ignoring these signals can be as disastrous as ignoring a flashing “low fuel” light in your car – you might end up stranded.

Types of Economic Indicators

Economic indicators are broadly categorized into three types based on their relationship to the overall economic cycle: leading, lagging, and coincident indicators. Leading indicators predict future economic activity, lagging indicators confirm past trends, and coincident indicators move in tandem with the overall economy. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for effective economic analysis and forecasting. Think of it like this: leading indicators are the early birds, lagging indicators are the night owls, and coincident indicators are the average folks, getting up and going to work with the rest of the crowd.

Examples of Leading, Lagging, and Coincident Indicators

Leading indicators provide an early warning system for the economy. For example, building permits often signal future construction activity, and consumer confidence surveys can anticipate changes in spending. A sharp increase in building permits suggests a boom in the construction sector, which will positively affect the overall economy in the near future, unless, of course, those permits are for giant hamster wheels.

Lagging indicators confirm what has already happened. The unemployment rate, for instance, typically rises after a recession has begun, while corporate profits usually lag behind economic growth. Think of these as the confirmation emails you receive after you’ve already completed the transaction – the information is useful, but not timely.

Coincident indicators, as the name suggests, happen at the same time as the economic changes they reflect. Industrial production, personal income, and manufacturing and trade sales are prime examples. These indicators provide a snapshot of the current economic situation – a picture of the present moment.

Comparison of Economic Indicators

| Indicator Type | Example | Source | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leading | Consumer Confidence Index | Conference Board | Measures consumer optimism about the economy. |

| Leading | Building Permits | Census Bureau | Indicates future construction activity. |

| Lagging | Unemployment Rate | Bureau of Labor Statistics | Reflects job losses and gains after economic changes. |

| Lagging | Average Prime Rate | Federal Reserve | Interest rate charged by banks to their most creditworthy customers, which typically lags behind other economic shifts. |

| Coincident | Gross Domestic Product (GDP) | Bureau of Economic Analysis | Measures the total value of goods and services produced. |

| Coincident | Industrial Production | Federal Reserve | Reflects the output of factories, mines, and utilities. |

Key Macroeconomic Indicators

Understanding macroeconomic indicators is like having a crystal ball (a slightly cloudy one, admittedly) for the economy. These indicators give us a glimpse into the overall health and performance of a nation’s economy, helping us understand trends and make informed decisions – whether you’re a seasoned investor or just trying to figure out if that new avocado toast is still affordable.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and its Components

GDP, or Gross Domestic Product, is the total value of all goods and services produced within a country’s borders in a specific period, usually a year or a quarter. Think of it as the country’s economic output – the sum total of everything produced, from tiny artisanal soaps to massive aircraft carriers. GDP is broken down into four main components, each telling a different part of the economic story:

GDP = Consumption + Investment + Government Spending + Net Exports

Consumption represents spending by households on goods and services. Investment includes spending by businesses on capital goods (machinery, equipment, etc.) and residential construction. Government spending covers government purchases of goods and services. Finally, net exports are the difference between exports (goods and services sold to other countries) and imports (goods and services bought from other countries). Each component plays a vital role, and changes in one can significantly impact the overall GDP.

GDP Calculation Methods

There are three primary methods to calculate GDP, all theoretically leading to the same result (in a perfect world, at least): the expenditure approach, the income approach, and the production (or value-added) approach. The expenditure approach, as seen above, sums up all spending within the economy. The income approach adds up all the income earned in the production process (wages, profits, rents, etc.). The production approach sums the value added at each stage of production. While conceptually different, these methods provide valuable cross-checks on each other, helping economists ensure accuracy (or at least catch the really glaring errors).

Implications of Changes in GDP Growth Rate

Changes in the GDP growth rate are significant indicators of economic health. A rising GDP growth rate usually suggests a booming economy, with increased production, employment, and consumer spending. Conversely, a falling GDP growth rate, or negative growth (a recession!), points to economic slowdown, potential job losses, and decreased consumer confidence. Think of it like a car’s speedometer – a steadily increasing speed is good, while a sudden drop might mean you need to hit the brakes (or at least adjust your driving). The impact of these changes can be far-reaching, affecting everything from investment decisions to government policies. For example, a significant drop in GDP growth might lead to government intervention in the form of stimulus packages to boost the economy.

GDP Growth Rates Across Different Countries

Comparing GDP growth rates across different countries allows us to understand relative economic performance and identify potential investment opportunities (or areas to avoid). The following table shows hypothetical GDP growth rates for selected countries in 2023. Remember, these are *hypothetical* numbers for illustrative purposes only and don’t reflect actual data.

| Country | GDP Growth Rate (2023, Hypothetical %) |

|---|---|

| United States | 2.5 |

| China | 5.0 |

| Germany | 1.8 |

| Japan | 1.2 |

| Brazil | 3.0 |

Inflation and its Measurement: Economic Indicators Explanation Guide

Inflation, that sneaky economic villain, is the persistent increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy over a period of time. Think of it as the gradual shrinking of your purchasing power – your money buys less and less with each passing day. While a little inflation can be healthy for a growing economy (it encourages spending), runaway inflation can be disastrous, leading to economic instability and social unrest. The causes of inflation are multifaceted, ranging from increased demand exceeding supply (demand-pull inflation) to rising production costs (cost-push inflation). Government policies, particularly in managing the money supply, also play a significant role. Let’s delve into the fascinating (and sometimes frightening) world of inflation measurement.

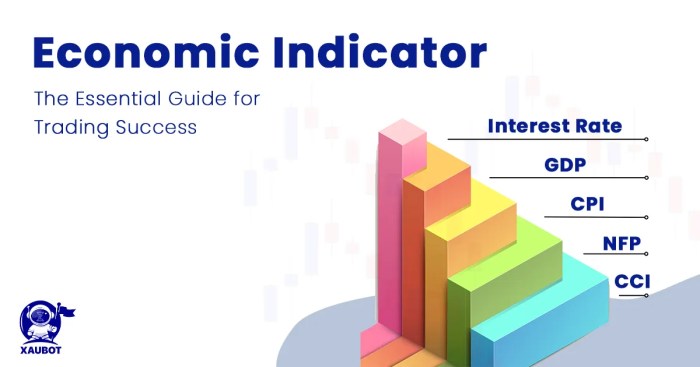

The Consumer Price Index (CPI)

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is the most widely used measure of inflation. It tracks the average change in prices paid by urban consumers for a basket of consumer goods and services. This “basket” includes everything from groceries and gasoline to housing and healthcare. Economists meticulously select these items, weighting them according to their relative importance in a typical consumer’s budget. For example, housing typically carries a much larger weight than, say, postage stamps. The CPI is calculated by comparing the cost of this basket of goods and services over time. A rising CPI indicates inflation, while a falling CPI suggests deflation. The CPI is not without its limitations; it may not perfectly capture the changing consumption patterns of consumers or the introduction of new products and technologies. However, it remains a crucial indicator for policymakers and economists alike.

The Producer Price Index (PPI)

While the CPI focuses on what consumers pay, the Producer Price Index (PPI) tracks the average change over time in the selling prices received by domestic producers for their output. This index measures price changes at the wholesale level, before goods reach consumers. The PPI provides an early warning system for potential inflation. If producer prices are rising, it suggests that these increased costs will eventually be passed on to consumers, leading to higher consumer prices and ultimately, inflation. Therefore, monitoring the PPI can give economists a heads-up on potential inflationary pressures before they show up in the CPI. Think of it as a sneak peek into the future of consumer prices.

The Impact of Inflation on the Economy and Consumers

Inflation’s effects ripple throughout the economy. For consumers, rising prices erode purchasing power, meaning their money buys less. This can lead to decreased living standards, especially for those on fixed incomes. Businesses face challenges in managing costs and pricing their products, potentially leading to decreased profits or even bankruptcies. High inflation can also lead to uncertainty in investment decisions, slowing down economic growth. Conversely, low and stable inflation is generally considered conducive to economic stability and growth. The impact of inflation, therefore, is not uniform and varies depending on the level and duration of the inflationary pressure, as well as the specific circumstances of the economy and individuals within it.

Historical Trends of Inflation in the United States

The following table shows the annual inflation rate in the United States, as measured by the CPI, for selected years. These figures highlight the volatility of inflation, ranging from periods of low inflation to periods of high inflation, even hyperinflation in certain historical periods.

| Year | Inflation Rate (%) |

|---|---|

| 1970 | 5.7 |

| 1980 | 13.5 |

| 1990 | 5.4 |

| 2000 | 3.4 |

| 2010 | 1.6 |

| 2020 | 1.4 |

| 2022 | 7.5 |

Unemployment and Labor Market Dynamics

The labor market, that bustling marketplace of skills and services, is a key driver of economic health. Understanding its intricacies, particularly the phenomenon of unemployment, is crucial for grasping the overall economic picture. Unemployment isn’t just a number; it represents lost potential, societal strain, and a significant drag on economic growth. Let’s delve into the fascinating (and sometimes frustrating) world of joblessness.

Unemployment, in its simplest form, is the state of being actively seeking employment but unable to find it. However, the reality is far more nuanced than this simple definition suggests. Different types of unemployment exist, each with its own causes and implications. The way we measure unemployment also plays a crucial role in how we understand and address the problem. And, as we’ll see, there’s a complex relationship between unemployment and inflation – a dance as unpredictable as a tango performed by caffeinated penguins.

Types of Unemployment

Unemployment isn’t a monolithic entity; it’s a multifaceted beast with several distinct forms. Frictional unemployment, for example, is the temporary unemployment experienced by individuals between jobs. It’s the time spent searching for a new position, updating resumes, and attending interviews. This type of unemployment is generally considered healthy, representing a dynamic labor market where individuals are making career transitions. Think of it as the brief intermission between acts in the grand opera of the labor market. Then there’s structural unemployment, a more stubborn beast. This occurs when there’s a mismatch between the skills possessed by workers and the skills demanded by employers. Technological advancements, industry shifts, or geographical imbalances can all contribute to structural unemployment. Finally, we have cyclical unemployment, the most dreaded type. This is unemployment directly related to the business cycle; during economic downturns, demand for goods and services falls, leading to layoffs and increased unemployment. Think of it as the orchestra tuning their instruments before the show begins, except instead of playing music, they’re waiting for the economy to pick up.

Calculating Unemployment Rates

Measuring unemployment isn’t as simple as counting the number of unemployed people. Official unemployment rates are typically calculated using a survey-based approach, such as the Current Population Survey (CPS) in the United States. The CPS randomly samples households and asks about their employment status. Individuals are classified as unemployed if they are actively seeking work but without a job. The unemployment rate is then calculated as the percentage of the labor force that is unemployed. The labor force itself consists of the employed and the unemployed (excluding those not actively seeking work, such as retirees or full-time students). This process, while seemingly straightforward, has its limitations. It doesn’t account for underemployment (working part-time when full-time work is desired) or discouraged workers (those who have given up looking for work). Therefore, the official unemployment rate often understates the true extent of labor market slack.

The Phillips Curve: Unemployment and Inflation, Economic Indicators Explanation Guide

The Phillips Curve illustrates the inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation. It suggests that lower unemployment rates are associated with higher inflation rates, and vice versa. This relationship isn’t always perfectly stable and has been subject to considerable debate among economists. The original Phillips Curve depicted a stable trade-off, implying policymakers could choose a point on the curve representing their desired balance between unemployment and inflation. However, the stagflation of the 1970s (high inflation coupled with high unemployment) challenged this view. Modern interpretations acknowledge that the relationship is more complex and influenced by factors such as supply shocks and expectations. While the exact shape and stability of the Phillips Curve remain debated, the underlying concept – a trade-off between unemployment and inflation – remains relevant in economic policymaking.

The Phillips Curve suggests a trade-off between unemployment and inflation, but this relationship isn’t always straightforward.

Factors Influencing Unemployment

Several factors influence unemployment levels. Understanding these factors is crucial for developing effective policies to mitigate unemployment.

Here’s a list of key influences:

- Technological advancements: Automation and technological progress can displace workers, leading to structural unemployment.

- Economic growth: Strong economic growth generally leads to lower unemployment, while recessions cause unemployment to rise.

- Government policies: Minimum wage laws, unemployment benefits, and training programs can all affect unemployment rates.

- Globalization and international trade: Increased competition from imports can lead to job losses in certain sectors.

- Demographics: The size and age structure of the labor force influence unemployment rates.

- Education and skills: A skilled workforce is less susceptible to unemployment.

- Labor market regulations: Stricter labor market regulations can increase unemployment by making it more difficult to hire and fire workers.

Interest Rates and Monetary Policy

Interest rates, the price of borrowing money, are the unsung heroes (or villains, depending on your perspective) of the economic world. They’re not as flashy as GDP growth or as immediately relatable as inflation, but their influence is pervasive and profound. Understanding how they work is key to understanding the economy’s overall health. This section will explore the fascinating world of interest rates and the central banks that orchestrate their movements.

The Role of Central Banks in Setting Interest Rates

Central banks, the guardians of a nation’s monetary system (think of them as the economic superheroes in tailored suits), play a pivotal role in setting interest rates. Their primary objective is usually to maintain price stability—keeping inflation at a healthy level—and to foster full employment. They achieve this largely through manipulating interest rates. A central bank might lower interest rates to stimulate the economy during a recession, encouraging borrowing and spending. Conversely, they might raise rates to cool down an overheating economy, curbing inflation. Think of it as a finely tuned economic thermostat, constantly adjusting to maintain the ideal temperature.

Impact of Interest Rate Changes on Investment and Consumption

Changes in interest rates have a ripple effect throughout the economy, significantly influencing both investment and consumption. Lower interest rates make borrowing cheaper, encouraging businesses to invest in new equipment and expansion projects. Consumers, too, are more likely to take out loans for large purchases like houses or cars. This increased spending boosts economic activity. Conversely, higher interest rates make borrowing more expensive, dampening investment and consumption. Businesses postpone expansion plans, and consumers delay major purchases. It’s a delicate balancing act—too much stimulus can lead to inflation, while too much restraint can lead to recession.

Tools Used by Central Banks to Control Inflation and Unemployment

Central banks employ a variety of tools to manage inflation and unemployment, with interest rate adjustments being the most prominent. The primary tool is the policy interest rate, the rate at which banks borrow money from the central bank. Changes to this rate influence other interest rates throughout the economy. Beyond this, central banks can also use quantitative easing (QE), where they inject money directly into the financial system by purchasing assets, or reserve requirements, which dictate the amount of money banks must hold in reserve. These tools are used strategically to influence money supply and credit conditions, achieving the desired economic outcomes. It’s a complex game of economic chess, requiring careful planning and execution.

A Decade of Interest Rate Changes

The following timeline illustrates a simplified overview of interest rate changes over the past decade. Note that this is a highly generalized representation, and specific rates varied across different countries and types of interest rates. The actual data would need to be sourced from a reliable financial institution for each specific country’s central bank.

| Year | General Trend | Illustrative Example (Hypothetical) |

|---|---|---|

| 2014-2015 | Gradual Decrease | Central bank lowers its policy rate from 2% to 0.5% to stimulate growth following a period of slow economic activity. |

| 2016-2018 | Near-Zero or Negative Rates | In some regions, negative interest rates were implemented in a desperate attempt to encourage lending and investment in a sluggish economy. |

| 2019-2021 | Further Stimulus Due to Pandemic | Significant increase in quantitative easing and near-zero interest rates to combat the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. |

| 2022-Present | Rate Hikes to Combat Inflation | Aggressive interest rate increases to curb rising inflation, potentially leading to a slowdown in economic growth. |

Exchange Rates and International Trade

Ah, exchange rates – the invisible hand that slaps your wallet when you travel abroad. Understanding them is crucial, not just for budget travelers, but for anyone wanting to grasp the global economic dance. These rates, essentially the price of one currency in terms of another, are far from static; they fluctuate constantly, influenced by a multitude of factors, creating both opportunities and challenges for international trade.

Factors Influencing Exchange Rates

Numerous factors contribute to the ever-shifting sands of exchange rates. Think of it as a complex game of tug-of-war, with various forces pulling in different directions. These forces can be broadly categorized as economic, political, and psychological. Economic factors often dominate, however.

- Interest Rate Differentials: Higher interest rates in a country tend to attract foreign investment, increasing demand for that country’s currency and thus strengthening it. Imagine a global savings account; everyone wants the highest interest, leading to a currency rush.

- Inflation Rates: A country with high inflation generally sees its currency weaken. This is because higher prices reduce the purchasing power of the currency, making it less attractive to foreign investors. It’s like a shrinking pie – everyone wants a bigger slice, so they move to countries with more stable prices.

- Government Debt: High levels of government debt can erode investor confidence, leading to a weaker currency. Think of it like a credit card with maxed-out limits – it’s less appealing to lenders.

- Balance of Payments: A country with a large current account surplus (more exports than imports) usually has a stronger currency. This is because more foreign currency flows into the country. It’s like having a surplus of foreign goodies; you can trade them for your currency.

- Political Stability: Political uncertainty or instability can cause a currency to weaken. Investors flee uncertainty, leading to reduced demand for the currency. Think of it like a storm; everyone heads for cover, leaving the currency exposed.

Impact of Exchange Rate Fluctuations on International Trade

Exchange rate volatility can significantly impact international trade. A strengthening currency makes imports cheaper but exports more expensive, potentially harming domestic producers. Conversely, a weakening currency makes exports cheaper and imports more expensive, boosting domestic producers but potentially leading to higher inflation for consumers. It’s a delicate balancing act.

Implications of a Strong vs. Weak Currency

A strong currency, while making imports cheaper, can hurt export-oriented industries. Think of a country like Switzerland, known for its strong franc. While Swiss consumers benefit from cheaper imports, its watchmakers face stiffer competition from countries with weaker currencies. Conversely, a weak currency makes exports more competitive but can lead to higher import prices, potentially fueling inflation. A classic example is Japan, which periodically grapples with a weaker yen to boost its export-driven economy.

Examples of Exchange Rate Effects on Different Sectors

The impact of exchange rates is not uniform across all sectors. For example, tourism benefits from a weak domestic currency as it attracts more foreign visitors. Conversely, import-dependent industries like electronics manufacturing might suffer from a weak currency due to higher input costs. The agricultural sector can also be significantly affected, with a strong currency potentially harming export-oriented farmers while benefiting consumers who can afford cheaper imported food. The automotive industry is another prime example; a strong domestic currency can make imported vehicles cheaper, impacting domestic car manufacturers.

Government Spending and Fiscal Policy

Government spending, the lifeblood of many a nation’s economy (and the bane of many a budget-conscious citizen!), plays a pivotal role in shaping economic activity. Think of it as the government’s powerful lever, used to boost or dampen the economic engine. It’s a complex dance of allocating resources, influencing markets, and (hopefully) achieving desired economic outcomes. Sometimes it’s a graceful waltz, sometimes a frantic jig – but it’s always fascinating to observe.

Types of Government Spending

Government spending isn’t just a monolithic blob; it’s a diverse portfolio of investments and expenditures. Understanding the different categories helps us analyze its overall impact. These expenditures are broadly categorized to better understand their effects on the economy and the different sectors they support.

- Infrastructure Spending: This includes investments in roads, bridges, public transportation, and other physical capital. Think of the grand projects that shape cities and connect regions – these investments stimulate economic growth by creating jobs and improving productivity. The construction of the Panama Canal, for example, had a profound and lasting impact on global trade and economic activity.

- Social Welfare Spending: This encompasses programs designed to support vulnerable populations, such as unemployment benefits, social security, and healthcare. These programs act as automatic stabilizers, cushioning the economy during downturns by providing income support to those who need it most. The expansion of social security in the United States, for example, significantly reduced poverty among the elderly.

- Defense Spending: A significant portion of government spending is often allocated to defense. While less directly stimulating to the broader economy than infrastructure projects, it nevertheless creates jobs and supports related industries. The post-WWII boom in the US economy, partially fueled by defense spending, is a testament to this effect.

- Education Spending: Investments in education are crucial for long-term economic growth. A well-educated workforce is a productive workforce. The significant investment in education following the Sputnik launch in the Soviet Union spurred a technological boom in the United States, a direct result of a government initiative.

Impact of Fiscal Policy on GDP and Inflation

Fiscal policy, the government’s use of spending and taxation to influence the economy, has a direct impact on both GDP and inflation. Increased government spending, for instance, can boost aggregate demand, leading to higher GDP growth. However, if this spending is not carefully managed, it can also fuel inflation by putting upward pressure on prices. Conversely, decreased government spending can curb inflation but might also slow economic growth. The delicate balance between stimulating growth and controlling inflation is a constant challenge for policymakers. The US government’s response to the 2008 financial crisis, involving significant fiscal stimulus, is a case in point – while it helped prevent a deeper recession, it also contributed to a period of higher inflation.

Government Budget Allocation: A Visual Representation

Imagine a pie chart. The whole pie represents the total government budget. A large slice, perhaps the biggest, is dedicated to Social Welfare programs – think healthcare, pensions, and unemployment benefits. Another substantial slice goes to Defense spending, representing the cost of national security. A smaller, but still significant, slice is allocated to Infrastructure – roads, bridges, and public works. Smaller slices represent Education, Research & Development, and other essential government functions. The relative sizes of these slices will vary depending on the country and its priorities, but this provides a general picture of how government resources are typically distributed. It’s a complex equation, juggling competing needs and priorities.

Interpreting Economic Data

Interpreting economic data is like deciphering a cryptic crossword – challenging, sometimes frustrating, but ultimately rewarding if you crack the code. Understanding the nuances of these indicators is crucial for making informed decisions, whether you’re a seasoned economist or just a curious citizen trying to understand the state of the economy. This section will equip you with the tools to navigate this complex landscape.

Demonstrating Interpretation of Key Economic Indicators

Economic indicators rarely speak for themselves; they need context and comparison. For instance, a rise in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) might signal inflation, but only when considered alongside other factors like wage growth and productivity. A significant increase in CPI coupled with stagnant wages suggests a genuine erosion of purchasing power, a far cry from a small CPI increase accompanied by robust wage growth. Similarly, a jump in unemployment figures needs to be analyzed in relation to the labor force participation rate to determine whether it reflects a genuine economic slowdown or simply a shift in workforce demographics. Effective interpretation requires comparing current data to historical trends, seasonal adjustments, and other related indicators. Think of it as a detective piecing together clues – one indicator alone rarely tells the whole story.

Limitations of Using Economic Indicators

Economic indicators, while invaluable, aren’t perfect. They are often lagging indicators, meaning they reflect past economic activity rather than providing real-time snapshots. For example, GDP figures are usually released with a significant time lag. Furthermore, these indicators are subject to revision as more complete data becomes available. The data collection methods themselves can introduce biases, and the indicators may not fully capture the complexity of the economy. Consider the limitations of using GDP as a sole measure of economic well-being; it doesn’t account for factors like income inequality or environmental sustainability. Think of them as snapshots of a moving target – they provide a glimpse, but not the complete picture.

Using Economic Indicators in Forecasting

Economic forecasting relies heavily on the analysis of economic indicators. Economists use various econometric models and statistical techniques to predict future economic trends based on past data and current indicator values. For example, a consistent upward trend in consumer confidence indices might suggest future increases in consumer spending and overall economic growth. Conversely, a sharp decline in manufacturing purchasing managers’ index (PMI) could signal an impending recession. These forecasts, however, are inherently uncertain; they’re educated guesses, not guarantees. The 2008 financial crisis serves as a stark reminder of the limitations of economic forecasting, highlighting the unpredictable nature of economic systems and the potential for unforeseen events to derail even the most sophisticated models.

Identifying Potential Biases in Economic Data

Data bias is a significant challenge in economic analysis. For example, sampling bias can occur if the data collection method doesn’t accurately represent the entire population. Measurement error, arising from inaccuracies in data collection or reporting, is another common issue. Furthermore, there’s the risk of survivorship bias, where only successful entities are included in the data, skewing the results. Consider, for instance, studies of successful businesses that might inadvertently ignore the many failed ventures, leading to an overly optimistic view of entrepreneurial success. Identifying these biases requires a critical and skeptical approach to data analysis, including careful examination of data collection methodologies and potential sources of error. It’s about asking the right questions and looking beyond the surface numbers.

Final Review

So, there you have it – a whirlwind tour of the economic indicators landscape! We’ve journeyed from the lofty heights of GDP to the nitty-gritty details of unemployment rates, uncovering the stories hidden within the numbers. While economic forecasting remains an inexact science, understanding these key indicators provides a crucial framework for interpreting economic trends and making informed decisions, whether you’re a seasoned investor, a curious student, or just someone who enjoys a good economic puzzle. Now go forth and analyze!

FAQ Section

What is the difference between nominal and real GDP?

Nominal GDP is calculated using current prices, while real GDP adjusts for inflation, providing a clearer picture of actual economic growth.

How is the unemployment rate calculated?

The unemployment rate is calculated by dividing the number of unemployed individuals by the total labor force (employed plus unemployed).

What are some limitations of using economic indicators?

Economic indicators can be subject to revision, may not capture the full picture of economic activity (e.g., the informal economy), and can be influenced by various factors, leading to potential biases.

How do exchange rates affect consumers?

Exchange rate fluctuations directly impact the prices of imported goods and services, influencing consumer spending and inflation.