Ratio Analysis Interpretation Guide: Embark on a whimsical yet rigorous journey into the heart of financial statement analysis! Forget dry spreadsheets and yawn-inducing calculations; we’ll unravel the mysteries of liquidity, profitability, solvency, and efficiency ratios with a blend of formal precision and delightful absurdity. Prepare to be both enlightened and entertained as we dissect the financial health of companies with the keen eye of a seasoned accountant and the playful spirit of a mischievous accountant’s pet ferret.

This guide will equip you with the tools to interpret financial ratios, understand their implications, and even impress your colleagues (or perhaps just your ferret) with your newfound expertise. We’ll cover the major ratio categories, demonstrate calculations using engaging examples, and explore the subtle art of comparative analysis. Buckle up, it’s going to be a wild ride!

Introduction to Ratio Analysis

Ratio analysis, my friends, is the financial equivalent of a detective’s magnifying glass. It allows us to peer into the heart of a company’s financial statements, uncovering hidden truths and revealing whether a business is a sparkling gem or a dusty old trinket. Essentially, it’s the art of transforming raw financial data into meaningful insights, allowing investors, creditors, and management to make informed decisions. Think of it as financial statement forensics – but hopefully, less messy.

Ratio analysis achieves its magic by comparing different line items within a company’s financial statements – balance sheets, income statements, and cash flow statements – to generate meaningful ratios. These ratios, expressed as percentages, fractions, or multiples, provide a standardized way to assess a company’s performance across various aspects of its operations. By comparing these ratios over time or against industry benchmarks, we can gain a comprehensive understanding of a company’s financial health and prospects. It’s like having a secret decoder ring for financial statements!

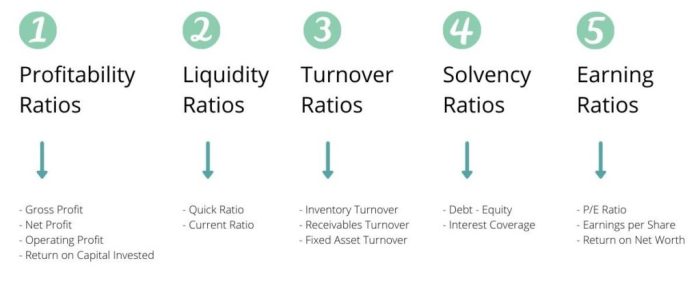

Categories of Financial Ratios, Ratio Analysis Interpretation Guide

Financial ratios are broadly categorized to provide a focused lens on specific aspects of a company’s performance. These categories aren’t mutually exclusive; often, one ratio will provide clues relevant to multiple categories. Understanding these categories is crucial for a holistic financial analysis.

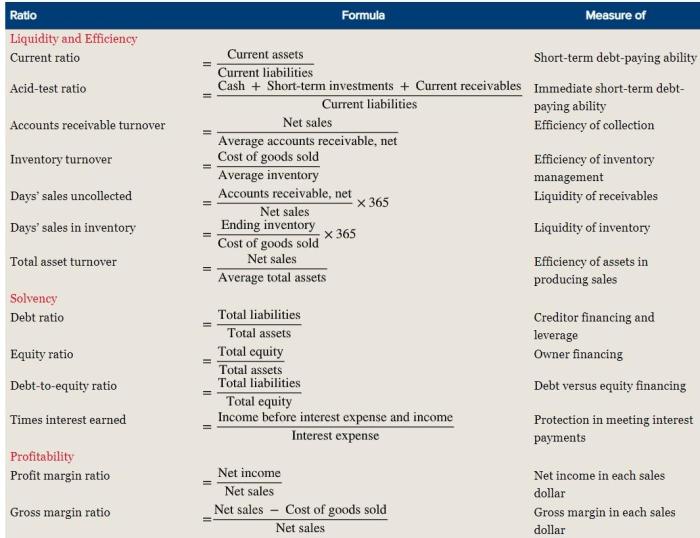

- Liquidity Ratios: These ratios assess a company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations. Think of it as checking if the company has enough readily available cash to pay its bills. Common examples include the Current Ratio (Current Assets / Current Liabilities) and the Quick Ratio ((Current Assets – Inventory) / Current Liabilities). A high ratio suggests strong liquidity, while a low ratio may signal potential financial distress. For example, a company with a current ratio of 2.0 is generally considered to have a healthy level of liquidity, suggesting they have twice the amount of current assets to cover their current liabilities.

- Profitability Ratios: These ratios measure a company’s ability to generate profits from its operations. This is where we see how efficiently a company is turning sales into profits. Key examples include Gross Profit Margin (Gross Profit / Revenue), Net Profit Margin (Net Income / Revenue), and Return on Equity (Net Income / Shareholders’ Equity). A consistently high profit margin usually indicates a successful business model, while declining margins might warrant further investigation.

- Solvency Ratios: These ratios gauge a company’s ability to meet its long-term obligations. This is a measure of the company’s overall financial stability and its capacity to handle its debts over the long haul. Important ratios in this category include the Debt-to-Equity Ratio (Total Debt / Shareholders’ Equity) and the Times Interest Earned Ratio (EBIT / Interest Expense). A high debt-to-equity ratio might suggest a high level of financial risk, while a low times interest earned ratio could indicate difficulty in meeting interest payments.

- Efficiency Ratios: These ratios evaluate how effectively a company manages its assets and liabilities to generate sales and profits. They focus on the speed and efficiency of various operational aspects. Common examples include Inventory Turnover (Cost of Goods Sold / Average Inventory) and Asset Turnover (Revenue / Average Total Assets). A high inventory turnover suggests efficient inventory management, while a high asset turnover indicates that the company is effectively using its assets to generate sales.

Context Matters: Industry and Company Specifics

While the ratios themselves are important, it’s crucial to remember that they don’t exist in a vacuum. Interpreting ratios requires considering the specific industry and the unique circumstances of the company being analyzed. A low current ratio might be perfectly acceptable for a grocery store (high inventory turnover) but disastrous for a construction company (large capital expenditures). Comparing a company’s ratios to industry averages provides a valuable benchmark, highlighting areas of strength and weakness relative to its peers. Further, understanding the company’s history, its strategic direction, and any significant external factors affecting its performance is essential for a nuanced and accurate interpretation. Simply put, context is king (or queen, or non-binary monarch, depending on your preference) in ratio analysis.

Liquidity Ratios

Liquidity ratios are the financial equivalent of a well-stocked emergency kit – essential for navigating unexpected storms. They tell us if a company has enough readily available assets to meet its short-term obligations. Without sufficient liquidity, even the most profitable business can find itself stranded, unable to pay its bills. Think of it as the financial version of “Do you have enough cash to make it to payday?” Let’s delve into the fascinating world of assessing a company’s ability to pay its bills promptly.

Liquidity Ratio Calculations and Interpretations

Liquidity ratios assess a company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations using its current assets. A higher ratio generally indicates better liquidity, but excessively high ratios might suggest inefficient asset management – think of it as hoarding cash instead of investing it wisely. The sweet spot lies in a balance between sufficient liquidity and efficient asset utilization. Let’s examine three key liquidity ratios: the current ratio, the quick ratio, and the cash ratio, each offering a slightly different perspective on a company’s short-term financial health.

| Ratio Name | Formula | Calculation (Example Data) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Ratio | Current Assets / Current Liabilities | ($150,000 / $100,000) = 1.5 | A current ratio of 1.5 suggests the company has $1.50 in current assets for every $1.00 in current liabilities. This is generally considered a healthy ratio, indicating sufficient liquidity to meet short-term obligations. However, the ideal ratio varies by industry. |

| Quick Ratio (Acid-Test Ratio) | (Current Assets – Inventory) / Current Liabilities | ($150,000 – $50,000) / $100,000 = 1.0 | The quick ratio of 1.0 indicates that the company has $1.00 in quick assets (excluding inventory) for every $1.00 in current liabilities. This is a more conservative measure of liquidity than the current ratio, as inventory might not be easily converted to cash. |

| Cash Ratio | (Cash + Cash Equivalents) / Current Liabilities | ($20,000 / $100,000) = 0.2 | A cash ratio of 0.2 suggests the company has only $0.20 in cash and cash equivalents for every $1.00 in current liabilities. This is the most stringent liquidity measure, highlighting the company’s immediate cash position. A low cash ratio might indicate potential short-term cash flow issues. |

Comparison of Liquidity Ratios

The current ratio, quick ratio, and cash ratio provide a tiered assessment of liquidity. The current ratio offers a broad overview, incorporating all current assets. The quick ratio provides a more conservative view by excluding inventory, which might not be readily convertible to cash. Finally, the cash ratio focuses solely on the most liquid assets – cash and cash equivalents – offering the most immediate picture of a company’s ability to meet its immediate obligations. Each ratio contributes to a comprehensive understanding of a company’s short-term financial health; using them in conjunction provides a much more nuanced picture than any single ratio alone. Consider them as a financial detective team, each bringing a unique perspective to solve the case of a company’s liquidity.

Profitability Ratios

Profitability ratios, the lifeblood of any business, reveal the efficiency with which a company transforms its efforts into, you guessed it, profits! These ratios are like a financial x-ray, showing the inner workings of a company’s revenue generation and cost management. Understanding these ratios is crucial for investors, creditors, and even the company itself to assess its financial health and make informed decisions. Let’s dive into the juicy details.

Profitability ratios are calculated using data readily available from a company’s income statement and balance sheet. They provide a comprehensive picture of a company’s performance over time and compared to its competitors. A consistent upward trend in these ratios generally indicates a healthy and growing business, while a downward trend may warrant a closer examination of the company’s operations and strategies. Think of them as your financial fortune tellers, but instead of tea leaves, they use numbers.

Gross Profit Margin

The gross profit margin reveals how effectively a company manages its direct costs of production. It’s calculated as:

Gross Profit Margin = (Revenue – Cost of Goods Sold) / Revenue

. A high gross profit margin suggests efficient production and pricing strategies, while a low margin might indicate issues with cost control, pricing pressure, or obsolete inventory. For example, a luxury car manufacturer typically boasts a high gross profit margin due to high prices and relatively low production costs compared to its revenue, whereas a grocery store usually has a lower gross profit margin due to lower profit margins on each item and higher volume sales. Factors influencing this ratio include pricing strategies, input costs, and production efficiency.

Operating Profit Margin

Operating profit margin shows profitability from core operations, excluding interest and taxes. The formula is:

Operating Profit Margin = Operating Income / Revenue

. A high operating profit margin suggests strong operational efficiency and effective cost management across the board. A low margin might signal issues such as high operating expenses or weak pricing power. For example, a company that streamlines its operations and reduces waste will likely see a higher operating profit margin. Conversely, a company struggling with high overhead costs will have a lower margin. Factors influencing this ratio include operating expenses, sales volume, and pricing strategies.

Net Profit Margin

The net profit margin represents the ultimate profitability after all expenses, including interest and taxes, are deducted. It’s calculated as:

Net Profit Margin = Net Income / Revenue

. This ratio is the bottom line; a high net profit margin indicates strong overall profitability and efficient management of all aspects of the business. A low net profit margin might indicate high operating costs, excessive financing costs, or low sales. For example, a company with a high net profit margin is likely to attract more investors and have greater financial stability. Conversely, a consistently low net profit margin may indicate the need for significant changes in business strategy. Factors influencing this ratio encompass all aspects of the business, from revenue generation to expense management.

Return on Assets (ROA)

Return on assets measures how effectively a company utilizes its assets to generate profit. The formula is:

Return on Assets (ROA) = Net Income / Total Assets

. A high ROA indicates efficient asset utilization, while a low ROA might signal underutilized assets or inefficient management. For example, a company with a high ROA is considered to be well-managed and efficient. Conversely, a low ROA might indicate that a company is not using its assets effectively. Factors influencing this ratio include asset turnover, net profit margin, and the mix of assets.

Return on Equity (ROE)

Return on equity measures the return generated on shareholder investments. It’s calculated as:

Return on Equity (ROE) = Net Income / Shareholder Equity

. A high ROE suggests a company is generating strong returns for its shareholders, while a low ROE may indicate less efficient use of shareholder capital. For example, a high ROE is generally attractive to investors, signaling potential for strong future returns. A low ROE might indicate that a company is not effectively using its equity financing to generate profits. Factors influencing this ratio include net profit margin, financial leverage, and asset turnover.

Solvency Ratios

Solvency ratios, unlike their more flamboyant cousins, the liquidity ratios (who always seem to be throwing lavish parties with readily available cash), are the quiet, dependable members of the financial statement family. They offer a glimpse into a company’s long-term financial health, whispering secrets about its ability to meet its long-term obligations. Ignoring them is like ignoring the structural engineer’s report before building a skyscraper – you might get away with it, but the consequences could be catastrophic.

Solvency ratios assess a company’s ability to survive and thrive over the long haul, focusing on its capital structure and its ability to manage debt. They provide a crucial perspective that liquidity ratios alone cannot offer, showing not just if a company can pay its bills tomorrow, but whether it can weather the storms of the next decade. Think of them as the company’s long-term survival insurance policy.

Debt-to-Equity Ratio

The debt-to-equity ratio is a classic solvency metric, illustrating the proportion of a company’s financing that comes from debt versus equity. A higher ratio indicates greater reliance on debt financing, which can be risky, especially during economic downturns. It’s essentially a measure of how much the company is “leveraging” itself – using borrowed money to amplify returns (and losses!).

Debt-to-Equity Ratio = Total Debt / Total Equity

A company with a debt-to-equity ratio of 2.0, for instance, has twice as much debt as equity. This might be perfectly acceptable for a mature, stable company in a low-interest-rate environment, but could be a warning sign for a young, rapidly growing business.

Times Interest Earned Ratio

The times interest earned ratio, often affectionately known as the “interest coverage ratio,” reveals how easily a company can meet its interest payments on debt. A higher ratio suggests a stronger ability to cover interest expenses, even during periods of reduced profitability. Think of it as a company’s financial cushion against interest payment defaults.

Times Interest Earned Ratio = Earnings Before Interest and Taxes (EBIT) / Interest Expense

A ratio of 5, for example, means a company’s earnings before interest and taxes are five times its interest expense, suggesting a healthy ability to manage its debt obligations. Conversely, a ratio below 1 indicates that a company’s earnings are not sufficient to cover its interest payments – a situation that can lead to serious financial distress.

Hypothetical Scenario: Acme Corp vs. Beta Industries

Let’s imagine two companies, Acme Corp and Beta Industries, both operating in the same industry. Acme Corp boasts a debt-to-equity ratio of 0.5 and a times interest earned ratio of 8. Beta Industries, on the other hand, has a debt-to-equity ratio of 3.0 and a times interest earned ratio of 1.5.

Acme Corp’s lower debt levels and high interest coverage suggest a more conservative financial strategy and a stronger ability to withstand economic shocks. Beta Industries, with its higher debt and lower interest coverage, is significantly more leveraged and potentially more vulnerable to financial difficulties if interest rates rise or profitability declines. While higher leverage can lead to higher returns, it also comes with significantly higher risk. In a downturn, Beta Industries would likely face far greater challenges than Acme Corp.

Efficiency Ratios

Efficiency ratios, unlike their more flamboyant cousins (profitability and liquidity ratios), are the unsung heroes of financial analysis. They don’t boast about profits or highlight the readily available cash, but instead, they quietly assess how well a company utilizes its assets to generate sales and manage its working capital. Think of them as the diligent employees who keep the machine running smoothly – often overlooked, but absolutely crucial for long-term success.

Efficiency ratios provide insights into a company’s operational effectiveness, revealing whether it’s a lean, mean, profit-making machine or a lumbering giant weighed down by inefficiency. A strong performance in these ratios suggests a company is maximizing its resources, while weak performance may indicate areas needing improvement, such as streamlining operations or optimizing inventory management. Ignoring these vital signs can be as disastrous as ignoring a check engine light.

Efficiency Ratio Overview

The following table summarizes some key efficiency ratios, providing a glimpse into the operational prowess of a company. Remember, context is key – a seemingly “bad” ratio in one industry might be perfectly acceptable in another.

| Ratio Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Inventory Turnover | This ratio measures how efficiently a company manages its inventory. It’s calculated as Cost of Goods Sold divided by Average Inventory. A higher ratio generally indicates efficient inventory management, suggesting strong sales and minimal waste from obsolete stock. For example, a grocery store would ideally have a much higher inventory turnover than a luxury car dealership. |

| Days Sales Outstanding (DSO) | DSO reveals how quickly a company collects payments from its customers. It’s calculated by dividing Accounts Receivable by Average Daily Sales. A lower DSO suggests efficient credit and collection processes, minimizing the time money is tied up in outstanding invoices. A company with a high DSO might need to tighten its credit policies or improve its billing procedures. |

| Asset Turnover | This ratio measures how effectively a company utilizes its assets to generate sales. It’s calculated by dividing Net Sales by Average Total Assets. A higher ratio implies efficient asset utilization, suggesting that the company is generating a high volume of sales relative to its asset base. However, a very high asset turnover might also indicate that the company is under-investing in assets, potentially hindering future growth. |

Industry Variations in Efficiency Ratio Interpretation

The interpretation of efficiency ratios varies significantly across industries. A high inventory turnover ratio is expected in industries with perishable goods (like groceries), but would be less relevant for industries dealing with durable goods (like construction equipment). Similarly, a high DSO might be acceptable in industries with long sales cycles (like aerospace), but would be a major red flag in industries with shorter sales cycles (like fast food). Understanding industry benchmarks is crucial for a meaningful interpretation of efficiency ratios; comparing a tech startup’s asset turnover to that of a utility company would be like comparing apples and…well, you get the idea. Context, my friends, is everything!

Limitations of Ratio Analysis

Ratio analysis, while a powerful tool for financial evaluation, isn’t a crystal ball. Like a particularly enthusiastic but slightly misguided accountant, it can sometimes lead you down a garden path paved with good intentions but ultimately leading to a rather prickly conclusion. Relying solely on ratios can be as risky as judging a book by its cover – you might miss the juicy bits inside.

The inherent limitations of ratio analysis stem from its reliance on historical financial data, which, let’s face it, is just a snapshot in time. It’s like trying to understand a whole movie based solely on a single frame – you get a glimpse, but not the full story. Furthermore, the interpretation of ratios is subjective and can vary depending on the analyst’s perspective and the industry context. What might be considered excellent performance in one sector could be a cause for concern in another.

Limitations Arising from the Nature of Financial Data

Financial data, the lifeblood of ratio analysis, is often subject to accounting practices that can influence the resulting ratios. Different accounting methods, such as FIFO (First-In, First-Out) and LIFO (Last-In, First-Out) for inventory valuation, can significantly impact reported profitability and efficiency. For example, during periods of inflation, LIFO will report lower profits than FIFO because the most recently purchased (and most expensive) inventory is assumed to be sold first. This difference can lead to wildly different interpretations of profitability ratios. Furthermore, the timing of revenue recognition and expense accruals can also distort the picture. It’s a bit like a magician pulling rabbits out of a hat – you see the result, but the sleight of hand is often hidden.

Qualitative Factors and Their Importance

Numbers tell only part of the story. Ratio analysis, being purely quantitative, ignores crucial qualitative factors that can significantly impact a company’s financial health. These factors might include management quality, employee morale, brand reputation, innovative capabilities, or even the overall economic climate. Imagine trying to assess the health of a patient based solely on their blood pressure – you’d miss a multitude of vital signs! Similarly, ignoring qualitative aspects could lead to flawed conclusions. For instance, a company with strong liquidity ratios might still be facing a serious threat from a disruptive new technology, a fact not reflected in its financial statements.

Potential for Manipulation and Misrepresentation

Let’s be honest, not everyone plays fair in the world of finance. Creative accounting practices and outright manipulation of financial data can significantly skew ratio analysis results. This can range from subtle adjustments to outright fraud, making it challenging to rely on the reported figures without critical scrutiny. Think of it as a financial game of poker – some players are bluffing, while others are holding a royal flush. Identifying these manipulations requires a keen eye and a healthy dose of skepticism. For example, a company might inflate its revenue figures by accelerating revenue recognition, leading to artificially high profitability ratios. This deceptive practice can fool unsuspecting investors.

Using Ratios for Comparative Analysis

Ratio analysis isn’t just about crunching numbers; it’s about telling a compelling story about a company’s financial health. And like any good story, it needs a strong narrative arc – a comparison over time and against competitors to truly shine. This section unveils the secrets to conducting powerful comparative analyses using the ratios we’ve already explored. Prepare to become a financial Sherlock Holmes!

Comparative analysis using ratios allows us to gain a deeper understanding of a company’s performance by placing its financial picture within a broader context. By comparing a company’s ratios over time and against its industry peers, we can identify trends, strengths, weaknesses, and potential areas for improvement. Think of it as giving your financial detective work a serious upgrade.

Trend Analysis: Tracking a Company’s Performance Over Time

Trend analysis involves comparing a company’s financial ratios over several periods, usually several years. This allows us to identify patterns and trends in the company’s performance. For example, a consistently declining profit margin might indicate underlying issues requiring investigation. Conversely, a steadily improving current ratio suggests improved liquidity management. To perform a trend analysis, simply calculate the relevant ratios for each period and present the data in a clear, visual format, such as a line graph or a table. Imagine watching a company’s financial story unfold year by year!

Let’s say we’re analyzing Acme Corp.’s Return on Equity (ROE) over five years. If the ROE has increased from 10% to 18% over this period, it suggests that the company has become more efficient at generating profits from its shareholders’ investments. However, a simple upward trend isn’t always a good sign. A sudden spike in ROE could also signal short-term gains rather than sustainable growth. Thorough investigation is crucial.

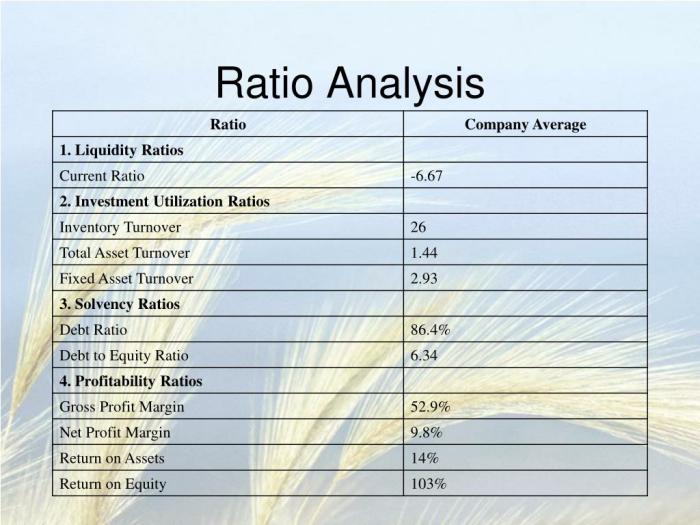

Benchmarking: Comparing a Company Against its Competitors

Benchmarking involves comparing a company’s financial ratios to those of its competitors or industry averages. This helps to identify areas where the company is performing well and areas where it needs improvement. For example, if a company’s profit margin is significantly lower than its competitors’, it might indicate inefficiencies in its operations or pricing strategies. This is like a financial race, and benchmarking shows you where you stand compared to other runners.

Consider comparing the quick ratio of a retail company to the average quick ratio of its competitors. A significantly lower quick ratio could indicate a higher risk of liquidity problems. This might suggest the need for improved inventory management or more efficient working capital management. Remember, context is key. Industry-specific factors can heavily influence these comparisons.

Presenting Comparative Data in a Clear and Understandable Way

Presenting your comparative analysis in a clear and effective manner is vital. A well-designed table is your best friend here. A four-column responsive HTML table can efficiently display data for trend analysis and benchmarking. The columns could be:

| Year/Competitor | Ratio Name | Company Value | Benchmark Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | Current Ratio | 1.8 | 1.5 (Industry Average) |

| 2023 | Current Ratio | 2.0 | 1.6 (Industry Average) |

| Beta Corp. | Current Ratio | N/A | 1.7 |

| Gamma Inc. | Current Ratio | N/A | 1.4 |

This table clearly shows Acme Corp.’s improving current ratio over time (trend analysis) and its position relative to competitors (benchmarking). Remember to clearly label your axes and provide context for your findings. A picture (in this case, a table) is worth a thousand numbers, but only if it’s clear and well-organized!

Closing Summary

So there you have it – a whirlwind tour of ratio analysis! We’ve journeyed from the simple elegance of liquidity ratios to the thrilling complexities of solvency and efficiency metrics. Remember, while numbers tell a story, context is king. Don’t just crunch the numbers; interpret them with a critical eye, considering the unique circumstances of each company and industry. Mastering ratio analysis isn’t just about crunching numbers; it’s about uncovering the hidden narratives within the financial statements, and perhaps even finding a few chuckles along the way. Happy analyzing!

FAQ Compilation: Ratio Analysis Interpretation Guide

What if a company has a high current ratio but low quick ratio?

This suggests the company relies heavily on inventory to meet its short-term obligations. While a high current ratio is generally positive, a low quick ratio raises concerns about the company’s ability to quickly convert assets into cash.

How do I account for seasonality when interpreting ratios?

Seasonality can significantly distort ratio analysis. It’s crucial to compare ratios across the same period (e.g., Q4 vs. Q4) or utilize rolling averages to smooth out seasonal fluctuations.

Can ratio analysis predict future performance?

Ratio analysis provides insights into past and current performance, but it’s not a crystal ball. It’s best used in conjunction with other forecasting methods and qualitative factors to anticipate future trends.