Economic Indicators Explanation Guide: Dive into the fascinating world of economic forecasting! We’ll unravel the mysteries of leading, lagging, and coincident indicators – think of them as economic crystal balls, tea leaves, and rearview mirrors, all rolled into one. Prepare for a journey through GDP, inflation, unemployment, and interest rates, where we’ll decipher the cryptic clues the economy keeps dropping. Get ready to become an economic Sherlock Holmes, armed with the knowledge to navigate the financial landscape with wit and wisdom (and maybe a magnifying glass).

This guide provides a comprehensive overview of key economic indicators, explaining their calculation, interpretation, and practical applications for individuals and businesses. We’ll explore different types of indicators, their relationships, and how they can be used to understand economic trends and make informed decisions. Expect charts, tables, and maybe even a limerick or two (okay, probably not a limerick).

Introduction to Economic Indicators

Navigating the sometimes-murky waters of the economy can feel like trying to assemble IKEA furniture without instructions – frustrating and potentially leading to a pile of useless parts. Fortunately, we have economic indicators: the instruction manual for the global economy (though, admittedly, it’s written in a language that can be as baffling as Swedish). Understanding these indicators is crucial, not just for seasoned economists, but for everyone from small business owners to individual investors – essentially, anyone who wants to avoid a financial flat-pack fail.

Economic indicators are essentially the vital signs of an economy. They’re the numbers, percentages, and indices that economists and analysts use to gauge the overall health and direction of an economy. Their purpose? To provide a snapshot of the current economic situation and, perhaps more importantly, to offer clues about what the future might hold. Think of them as the economy’s crystal ball (though, like any crystal ball, it’s not always perfectly clear).

Types of Economic Indicators

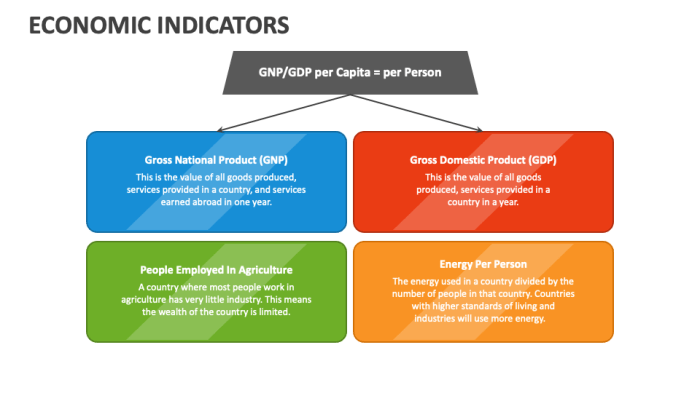

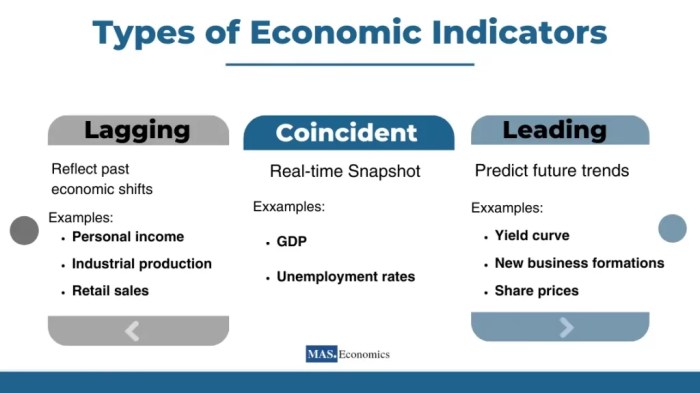

Economic indicators aren’t created equal; they offer different perspectives on the economic landscape, much like a news report might offer a variety of viewpoints on a single event. We categorize them based on their timing relative to economic fluctuations. Ignoring this categorization is like trying to build a house by starting with the roof – it’s not going to end well.

- Leading Indicators: These are the early birds of the economic world, providing clues about future economic activity. They anticipate changes in the overall economy before they actually happen. Think of them as the canary in the coal mine, but instead of coal, it’s economic growth. Examples include consumer confidence indices (how optimistic people feel about the economy), building permits (a sign of future construction activity), and stock market prices (reflecting investor sentiment). A significant drop in consumer confidence might signal a future economic slowdown, even if current economic data looks positive.

- Lagging Indicators: These indicators are the slowpokes of the bunch, reacting to economic changes only after they’ve already occurred. They confirm what’s already happened, offering a rearview mirror perspective on economic performance. Think of them as the accountant carefully reviewing the financial statements – useful, but the information is already in the past. Examples include the unemployment rate (often rises after a recession has begun), the average duration of unemployment (how long people are out of work), and outstanding commercial and industrial loans (reflecting past borrowing activity).

- Coincident Indicators: These indicators move in sync with the overall economy, providing a real-time snapshot of current economic activity. They’re like a live feed of the economy, showing what’s happening right now. Examples include personal income, manufacturing and trade sales, and employment (specifically, the number of employees on non-farm payrolls). A significant drop in personal income might indicate a concurrent weakening of the overall economy.

Leading Economic Indicators

Predicting the future is a tricky business, even for economists. Luckily, they’ve developed a clever system of “leading indicators” – essentially, economic crystal balls (though less prone to shattering). These indicators don’t guarantee the future, but they offer valuable clues about where the economy might be headed, allowing businesses and policymakers to prepare accordingly. Think of them as early warning systems for economic booms and busts, giving us a heads-up before the full impact hits.

Leading economic indicators are variables that tend to change *before* the overall economy changes. This “lead time” varies, of course, but it’s this predictive power that makes them so valuable. By analyzing these indicators, economists can gain insights into the likely direction of the economy in the months to come, potentially helping to mitigate risks and capitalize on opportunities. It’s like having a sneak peek at the economy’s next big move.

Key Leading Economic Indicators

Several key indicators consistently provide valuable insights into the future economic climate. Understanding their calculation methods and interpretations is crucial for making informed decisions. Let’s delve into five of the most important ones.

| Indicator Name | Description | Calculation Method | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yield Curve (Spread between 10-year and 2-year Treasury Yields) | The difference between the yield on a 10-year Treasury bond and a 2-year Treasury bond. | Subtracting the 2-year Treasury yield from the 10-year Treasury yield. | A flattening or inverting yield curve (where the 2-year yield exceeds the 10-year yield) is often seen as a predictor of an economic recession. A steepening curve, conversely, often suggests economic expansion. For example, the inversion of the yield curve in late 2022 was widely seen as a precursor to the economic slowdown of 2023. |

| Consumer Confidence Index | Measures consumer sentiment and expectations about the economy. | Calculated based on surveys asking consumers about their perceptions of current economic conditions and future expectations (employment, income, business conditions). The Conference Board conducts a prominent survey. | High consumer confidence suggests strong spending and economic growth. Low consumer confidence often precedes a slowdown in economic activity. For instance, a sharp decline in consumer confidence during the COVID-19 pandemic accurately reflected the subsequent economic downturn. |

| Building Permits | The number of permits issued for new residential and commercial construction. | Collected by government agencies (e.g., the U.S. Census Bureau). | A rise in building permits indicates increased investment and future economic activity. A decline suggests reduced investment and potential economic weakness. A surge in building permits prior to a housing boom provides a clear example. |

| Manufacturing New Orders | Orders placed for manufactured goods. | Collected from manufacturers and compiled by government agencies (e.g., the U.S. Census Bureau). | A rise in new orders indicates increased demand and production, suggesting future economic growth. A decline suggests weakening demand and potential contraction. The sharp increase in manufacturing orders following the initial phase of the pandemic recovery serves as a prime example. |

| Average Weekly Hours Worked in Manufacturing | The average number of hours worked per week by manufacturing employees. | Calculated from surveys of employers. | Increasing average weekly hours often suggest increased production and economic expansion, while a decrease can signal upcoming economic contraction. The decrease in average hours worked during the early stages of the 2008 financial crisis serves as a case in point. |

Lagging Economic Indicators

Lagging economic indicators, unlike their more flamboyant leading cousins, are the wallflowers of the economic dance. They don’t predict the future; they confirm what’s already happened. Think of them as the wise old owl, calmly observing the aftermath and offering a measured assessment of the economic party that just ended. They’re crucial, however, because they provide a solid, if belated, confirmation of economic trends, helping us understand the full picture and adjust our strategies accordingly.

Lagging indicators are the reliable, if somewhat slow, reporters of the economic scene. They paint a clearer picture of the past, allowing economists and businesses to better understand the impact of previous events and prepare for the future, even if that future is already here. This historical perspective is invaluable for refining economic models and informing long-term decisions.

Unemployment Rate

The unemployment rate measures the percentage of the labor force actively seeking employment but unable to find it. A rising unemployment rate typically signals a weakening economy, confirming a downturn that might have already been indicated by leading indicators. Conversely, a falling unemployment rate often signifies economic growth and expansion.

- Strength: Widely tracked and easily understood; a reliable indicator of the overall health of the labor market.

- Weakness: Lacks predictive power; it reflects past economic conditions, not future trends. The rate can also be influenced by factors other than economic growth, such as changes in labor force participation rates.

Corporate Profits

Corporate profits represent the earnings of businesses after deducting all expenses. A decline in corporate profits usually confirms a slowdown in economic activity, indicating reduced consumer spending and investment. Similarly, a surge in corporate profits suggests a healthy and expanding economy.

- Strength: Provides a direct measure of business performance and overall economic health; can be disaggregated to analyze specific sectors.

- Weakness: Can be influenced by accounting practices and one-time events; may not reflect the broader economic reality in all cases, as some businesses may be more resilient to economic downturns than others.

Average Prime Rate, Economic Indicators Explanation Guide

The average prime rate is the interest rate that commercial banks charge their most creditworthy customers. This rate typically lags behind other economic indicators, rising after an economic expansion and falling after a contraction. Changes in the prime rate reflect the overall direction of monetary policy and the state of the economy.

- Strength: Provides a clear indication of the cost of borrowing and reflects the overall monetary policy stance.

- Weakness: The prime rate is not always a precise reflection of the broader economy; it can be influenced by factors beyond economic conditions, such as regulatory changes or the actions of central banks.

Coincident Economic Indicators

Coincident indicators, unlike their leading and lagging brethren, are the party animals of the economic world. They’re happening *right now*, providing a snapshot of the current economic climate. Think of them as the paparazzi of the economy, capturing the action as it unfolds, rather than predicting it or analyzing its aftermath. While less useful for forecasting, their real-time data is invaluable for understanding the present state of affairs. They offer a crucial perspective, helping us gauge the effectiveness of current policies and understand the immediate implications of economic events.

Coincident indicators offer a simultaneous view of the economy, contrasting sharply with leading indicators that anticipate future trends and lagging indicators that react after the fact. Leading indicators are like fortune tellers, predicting the future (sometimes accurately, sometimes not so much!), while lagging indicators are like historians, meticulously documenting what has already transpired. Coincident indicators, however, are the live reporters, giving us the up-to-the-minute story.

Examples of Coincident Economic Indicators

The following indicators provide a real-time pulse of the economy. Their applications are diverse, from informing government policy decisions to guiding investment strategies. Understanding these indicators is like having a backstage pass to the economic performance.

- Personal Income: This measures the total income received by households, including wages, salaries, investment income, and government transfers. A rising personal income suggests a healthy economy, indicating increased consumer spending potential. A sharp decline, on the other hand, might signal impending economic trouble, similar to what we saw in the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic when lockdowns drastically reduced income for many.

- Industrial Production: This tracks the output of factories, mines, and utilities. It’s a broad measure of the manufacturing sector’s health, reflecting the overall capacity of the economy to produce goods. A sustained increase in industrial production usually points towards economic expansion, while a decrease could signal a contraction, much like the dip observed during the 2008 financial crisis.

- Manufacturing and Trade Sales: This indicator reflects the total sales of manufactured goods and trade, providing insight into the demand for goods and services. A surge in sales indicates strong consumer demand and economic activity, while a decline suggests weakening demand. The rapid increase in online sales during the pandemic, contrasted with a decrease in brick-and-mortar sales, is a prime example of how this indicator can shift rapidly.

- Employment: Measured by the unemployment rate, this is arguably the most widely watched coincident indicator. A low unemployment rate usually signals a strong economy with plenty of job opportunities, while a high rate often suggests economic weakness and potential recessionary pressures. The significant job losses during the 2008 recession are a stark reminder of this indicator’s importance.

Interpreting Economic Data

Interpreting economic data isn’t rocket science, but it does require a bit more than just squinting at numbers until they confess their secrets. Think of it as being a detective, but instead of solving murders, you’re solving the mysteries of the economy. We’ll arm you with the tools to decipher the clues hidden within those seemingly dry statistics.

Let’s imagine a hypothetical scenario. Our fictional country, “Econoland,” is experiencing some economic…interestingness. Unemployment is down, but consumer confidence is slightly wobbly. The housing market is booming, but inflation is creeping up. How do we make sense of this mixed bag of economic signals? This is where understanding economic cycles and the interplay of different indicators becomes crucial.

Economic Cycles and Indicator Interpretation

Economic cycles are the natural rhythm of the economy, like the ebb and flow of the tide. They swing between periods of expansion (boom times!) and contraction (uh oh!). Leading indicators, as we’ve discussed, provide early warnings of potential changes, like a canary in a coal mine (though hopefully with less dramatic consequences). Lagging indicators confirm what’s already happened, acting as the post-mortem examination. Coincident indicators, meanwhile, give us a snapshot of the current economic state. In our Econoland example, the booming housing market (coincident) might suggest an expansionary phase, but the rising inflation (coincident) tempers that enthusiasm. The wavering consumer confidence (leading) hints at potential future slowdown.

Using Indicators for Financial Decisions

Economic indicators are not crystal balls, but they are powerful tools for making more informed financial decisions. Imagine you’re considering a significant investment. If leading indicators point towards an economic downturn, you might want to proceed with caution, perhaps opting for less risky investments. Conversely, if indicators suggest robust growth, you might be more inclined to take on more risk. However, remember that no single indicator tells the whole story; it’s the overall picture painted by multiple indicators that truly matters. For example, a rising stock market (coincident) coupled with falling unemployment (coincident) and increasing consumer spending (coincident) would paint a picture of a healthy economy, suggesting a positive outlook for investment. Conversely, a rising inflation rate (coincident) combined with falling consumer confidence (leading) and a slowing manufacturing sector (lagging) would suggest a more cautious approach. Remember to always consider the context and the interplay of various indicators.

Inflation and its Indicators

Inflation: the relentless rise of prices, a phenomenon as exciting as watching paint dry (unless you’re a paint salesman, of course). It’s the economic equivalent of a slow-motion car crash, gradually eroding the purchasing power of your hard-earned cash. Understanding inflation is crucial for navigating the economic landscape, whether you’re a savvy investor or just trying to buy groceries without feeling like you’re robbing a bank.

Inflation’s impact on the economy is multifaceted and often unwelcome. High inflation can lead to decreased consumer spending as people become more cautious with their money. Businesses face challenges in planning and pricing their goods and services, potentially leading to reduced investment and economic slowdown. Conversely, a little inflation can be a sign of a healthy, growing economy, acting as a lubricant for economic activity. The key is finding that Goldilocks zone – not too hot, not too cold, but just right.

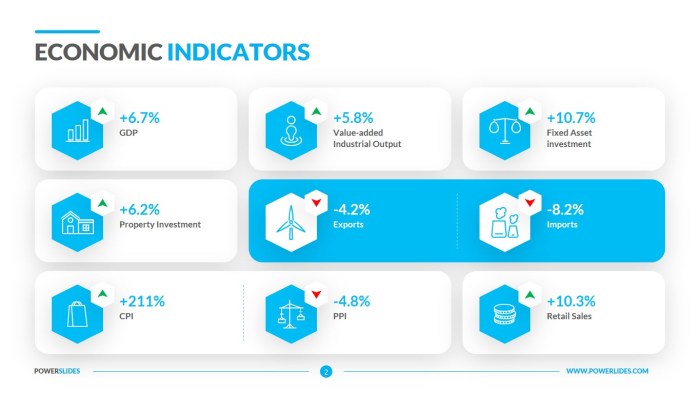

Consumer Price Index (CPI)

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is like the economy’s personal shopper, meticulously tracking the average change in prices paid by urban consumers for a basket of goods and services. This basket includes everything from the price of a gallon of milk to the cost of a Netflix subscription. Think of it as a detailed shopping list for the average household, constantly updated to reflect changes in prices. A rising CPI indicates inflation, while a falling CPI suggests deflation. For example, a significant increase in the CPI for energy could signal rising gas prices, affecting transportation costs and overall consumer spending.

Producer Price Index (PPI)

The Producer Price Index (PPI) shifts the focus from the consumer to the producer, tracking the average change in prices received by domestic producers for their output. It’s like a backstage pass to the economy, revealing the prices before they reach the consumer. A rise in the PPI often foreshadows an increase in the CPI, providing a valuable early warning system for inflation. For instance, a surge in PPI for raw materials, such as steel, will likely translate into higher prices for manufactured goods later on, impacting the CPI.

Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) Price Index

The Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) Price Index is the Federal Reserve’s preferred measure of inflation. Unlike the CPI, which uses a fixed basket of goods, the PCE index adjusts its basket to reflect changes in consumer spending habits. This dynamic approach provides a more accurate reflection of actual consumer spending and its response to price changes. For example, if consumers shift from buying expensive steaks to cheaper chicken due to inflation, the PCE index would reflect this shift, offering a more nuanced view of inflationary pressures than a fixed-basket index like the CPI. This flexibility makes it a valuable tool for policymakers in understanding the real-time impact of inflation on consumer behavior.

Inflation’s Impact on Consumer Behavior and Business Strategies

Changes in inflation significantly influence both consumer behavior and business strategies. High inflation often leads consumers to postpone major purchases, switch to cheaper alternatives, and increase savings. Businesses, in turn, might adjust pricing strategies, reduce production, or invest in automation to counter rising costs. For example, during periods of high inflation, consumers might delay buying a new car, opting for used vehicles or public transport instead. Businesses, on the other hand, might implement cost-cutting measures or raise prices to maintain profit margins, potentially triggering a wage-price spiral. Conversely, low inflation might encourage consumer spending and business investment, stimulating economic growth. The delicate dance between inflation, consumer behavior, and business strategies is a constant game of economic chess.

Unemployment and its Indicators

Unemployment, that delightful state of having more time than money, is a crucial economic indicator. While some might see it as a personal vacation extended indefinitely, economists view it as a significant measure of a nation’s economic health. Understanding its various forms and how it’s calculated helps us grasp the bigger picture of the economy – and maybe even plan that much-needed extended vacation (once we’re employed, of course!).

Unemployment isn’t a monolithic beast; it’s a multi-headed hydra with different types, each with its own implications.

Types of Unemployment

The different types of unemployment offer a nuanced understanding of the labor market’s dynamics. Failing to distinguish between them can lead to inaccurate interpretations of the overall economic situation. Think of it like trying to diagnose a patient’s illness without understanding the various symptoms.

- Frictional Unemployment: This is the temporary unemployment experienced by individuals between jobs. It’s like being between acts in a play – a brief pause before the next exciting scene. It’s usually short-lived and considered a natural part of a healthy economy. Think of someone graduating college and taking a few weeks to find the perfect role.

- Structural Unemployment: This occurs when there’s a mismatch between the skills workers possess and the skills demanded by employers. It’s like having a square peg and a round hole – they just don’t fit together. Technological advancements, industry shifts, or geographic limitations can all contribute to this type of unemployment. For example, a factory worker losing their job due to automation would experience structural unemployment.

- Cyclical Unemployment: This is the unemployment directly related to the business cycle. During economic downturns, businesses reduce production and lay off workers. This is unemployment tied directly to the economic tide – when the economy is doing poorly, so is employment. The Great Recession of 2008 is a prime example of a period of high cyclical unemployment.

- Seasonal Unemployment: This is unemployment that occurs due to seasonal changes in demand for labor. Think of lifeguards losing their jobs in the fall or holiday workers laid off after the New Year. It’s a predictable and temporary form of unemployment.

Calculating and Interpreting the Unemployment Rate

The unemployment rate, that number that makes headlines and causes economic anxieties, is calculated by dividing the number of unemployed individuals by the total labor force (employed plus unemployed). The result is expressed as a percentage. However, it’s crucial to remember that the unemployment rate doesn’t capture the entire picture. It excludes discouraged workers (those who have given up looking for work) and underemployed individuals (those working part-time but wanting full-time employment). Therefore, while a low unemployment rate might seem positive, it’s essential to consider these additional factors for a more comprehensive understanding. For example, an unemployment rate of 4% might seem low, but if a significant number of individuals are underemployed, the economic reality could be far more complex.

The Unemployment Rate = (Number of Unemployed / Total Labor Force) x 100

Unemployment and Economic Growth: A Visual Representation

Imagine a graph with two lines. The horizontal axis represents time, and the vertical axis represents both the unemployment rate (as a percentage) and the economic growth rate (as a percentage of GDP). The unemployment rate line will generally move inversely to the economic growth rate line. During periods of economic expansion (positive growth), the unemployment rate tends to decrease. Conversely, during economic contractions (negative growth or recession), the unemployment rate rises. The lines aren’t perfectly mirror images; there’s often a lag between changes in economic growth and changes in unemployment. Think of it as a game of catch – the economic growth rate throws the ball (change), and the unemployment rate catches it a bit later. This lag can be explained by factors like businesses’ hesitation to hire immediately during recovery or the time it takes for individuals to find new jobs after being laid off. The graph will show a general negative correlation, illustrating the inverse relationship between unemployment and economic growth.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

GDP: the ultimate economic rollercoaster! It’s the total value of all goods and services produced within a country’s borders in a specific time period, usually a year or a quarter. Think of it as the country’s economic report card – a high GDP generally means a healthy economy, while a low one suggests… well, let’s just say things might be a little bumpy. Understanding GDP is crucial for policymakers, businesses, and anyone interested in the economic pulse of a nation.

GDP is calculated in three primary ways, each offering a unique perspective on the economic engine. These approaches, while different, should theoretically yield the same result (though in reality, slight discrepancies exist due to data collection challenges and rounding errors). It’s like looking at a car from different angles – the front, side, and back all show the same vehicle, just from varying viewpoints.

Expenditure Approach to Calculating GDP

The expenditure approach sums up all spending on final goods and services within a country’s borders. This includes consumer spending (think shopping sprees!), investment spending (businesses buying new equipment), government spending (roads, schools, and those questionable military projects), and net exports (exports minus imports – because we need to account for what we sell to other countries and what we buy from them). Imagine a giant shopping mall representing the entire national economy; this approach adds up every purchase made in that mall. The formula is often represented as:

GDP = C + I + G + (X-M)

where C represents consumption, I investment, G government spending, X exports, and M imports. For example, a rise in consumer spending during the holiday season would directly contribute to an increase in the quarterly GDP.

Income Approach to Calculating GDP

The income approach focuses on the total income earned in producing goods and services. This includes wages, salaries, profits, rents, and interest. It’s like calculating the total earnings of everyone working in that giant shopping mall. This method considers the income generated at each stage of production, ensuring all contributions are accounted for. A significant increase in corporate profits, for example, would positively impact the GDP calculated using this approach.

Production Approach to Calculating GDP

The production approach, also known as the value-added approach, sums the value added at each stage of production. Imagine tracing the journey of a t-shirt, from cotton farming to the final sale in a retail store. This approach adds up the value added at each step – the farmer’s profit, the textile mill’s profit, the manufacturer’s profit, and finally, the retailer’s profit. This method ensures double-counting is avoided, giving a clear picture of the total value created. A boom in manufacturing, therefore, would significantly boost GDP as calculated by this approach.

Limitations of GDP as a Measure of Economic Well-being

While GDP is a valuable indicator, it’s not the be-all and end-all of economic health. It overlooks crucial aspects of well-being. For instance, it doesn’t account for things like income inequality (a country could have high GDP but vast disparities in wealth distribution), environmental degradation (economic growth might come at the cost of pollution), or the informal economy (untracked transactions like babysitting or freelance work). GDP is a great measure of economic activity, but it’s not a perfect reflection of overall societal well-being. Thinking of GDP as the sole metric for a nation’s success is like judging a book by its cover – you’re missing the entire story within.

Interest Rates and their Impact: Economic Indicators Explanation Guide

Interest rates, those often-misunderstood numbers that seem to mysteriously control our financial lives, are actually a crucial lever in the economic engine. They’re the price of borrowing money, and their fluctuations have a ripple effect throughout the economy, influencing everything from the price of your morning latte to the construction of a new skyscraper. Understanding how interest rates work is key to understanding the overall health of the economy.

Interest rates influence economic activity primarily by affecting borrowing costs. When interest rates are low, borrowing becomes cheaper, encouraging businesses to invest in expansion, consumers to take out loans for big purchases (like houses or cars), and governments to undertake ambitious infrastructure projects. This increased borrowing fuels economic growth, creating jobs and stimulating demand. Conversely, high interest rates make borrowing more expensive, cooling down the economy by discouraging investment and spending. Think of it as the economic equivalent of a speed bump – a gentle nudge to slow things down when things are getting a little too hot.

Interest Rates and Inflation

The relationship between interest rates and inflation is a classic economic seesaw. Central banks, like the Federal Reserve in the United States, often use interest rates as a tool to manage inflation. When inflation (the rate at which prices are rising) is too high, central banks typically raise interest rates. This makes borrowing more expensive, reducing consumer spending and business investment, thus slowing down the economy and ultimately curbing inflation. Conversely, when inflation is low or the economy is sluggish, central banks may lower interest rates to stimulate borrowing and spending, potentially reigniting economic growth. This delicate balancing act requires careful consideration of various economic indicators to avoid unintended consequences, such as triggering a recession. For example, the aggressive interest rate hikes in 2022 by many central banks aimed to combat high inflation demonstrate this principle in action, although the resulting economic slowdown was a side effect.

Interest Rate Changes and Investment Decisions

Changes in interest rates significantly impact investment decisions. Businesses often rely on borrowing to fund expansion projects or new equipment. When interest rates are low, the cost of borrowing is reduced, making these investments more attractive. Companies are more likely to take on debt to fund growth, leading to increased economic activity. Conversely, high interest rates increase the cost of borrowing, making investments less appealing. Businesses might postpone expansion plans or choose to invest less, leading to slower economic growth. For example, a tech startup might delay its expansion into a new market if interest rates rise significantly, making the cost of financing that expansion prohibitive.

Interest Rate Changes and Consumer Spending

Interest rates also influence consumer spending, particularly for large purchases like houses and cars, which are often financed through loans. Low interest rates make borrowing cheaper, encouraging consumers to take out loans and spend more. This increased consumer spending boosts economic activity. Conversely, high interest rates make borrowing more expensive, discouraging consumers from taking out loans and reducing overall spending. For example, the affordability of a mortgage is directly affected by interest rates; a rise in interest rates can significantly reduce the purchasing power of potential homebuyers, impacting the housing market and the wider economy.

Global Economic Indicators

Navigating the world of global economics can feel like trying to herd cats in a hurricane – chaotic, unpredictable, and frankly, a little hilarious. But fear not, intrepid economist-in-training! Understanding key global indicators can bring a touch of order (and perhaps a chuckle or two) to this wild ride. These indicators act as the economic equivalent of a global weather report, providing insights into the overall health and direction of the world economy.

Major Global Economic Indicators and Their Significance

Three major global economic indicators offer a fascinating glimpse into the interconnectedness of the world’s economies. These aren’t just numbers on a spreadsheet; they’re the pulse of the planet’s economic heartbeat. Misinterpreting them can lead to economic migraines, while understanding them can be incredibly profitable.

- World Trade Organization (WTO) Merchandise Trade Statistics: This indicator tracks the flow of goods across international borders. A significant increase suggests robust global economic activity, while a decline often signals trouble brewing on the horizon. Think of it as the global “stuff” meter – more stuff moving means more economic activity. A significant drop, however, could signal a looming recession.

- International Monetary Fund (IMF) World Economic Outlook: The IMF’s outlook isn’t just a prediction; it’s a comprehensive analysis of global economic trends, including growth forecasts for individual countries and regions. It’s the economic crystal ball, albeit one that occasionally needs recalibration. For example, the IMF’s predictions in 2020 regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic were constantly being revised as the situation unfolded.

- Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI): This composite index tracks the activity levels of purchasing managers in manufacturing and services sectors across various countries. A PMI above 50 generally indicates expansion, while a reading below 50 suggests contraction. It’s a real-time snapshot of the pulse of global industry, a sort of economic EKG. For example, a consistently high PMI in the technology sector might signal strong future growth in that industry, while a low PMI in the construction sector could indicate a slowdown in real estate investment.

Comparison of Economic Indicators: United States and Germany

Let’s compare the economic indicators of two economic powerhouses: the United States and Germany. While both are advanced economies, their strengths and vulnerabilities differ significantly.

The United States, driven by a robust consumer market and technological innovation, often shows higher GDP growth than Germany, but also exhibits higher levels of inflation and national debt. Germany, on the other hand, boasts a strong manufacturing sector and a more export-oriented economy, typically displaying lower inflation and debt levels, but often experiences slower GDP growth. The differences highlight the diverse approaches to economic management and the varying strengths of different economic models. One isn’t necessarily “better” than the other; they simply represent different paths to economic success (or, occasionally, economic hiccups).

Importance of Monitoring Global Economic Indicators for International Businesses

For international businesses, monitoring global economic indicators is akin to having a highly sophisticated early warning system. Fluctuations in global trade, currency exchange rates (which are often influenced by indicators), and consumer confidence can significantly impact a company’s profitability and competitiveness. Understanding these indicators allows businesses to make informed decisions about investment, production, and expansion strategies, mitigating risks and seizing opportunities in a dynamic global marketplace. Ignoring these indicators is like navigating a crowded marketplace blindfolded – you might stumble upon a treasure, but you’re more likely to trip over a very expensive obstacle.

Concluding Remarks

So, there you have it – a whirlwind tour of the economic indicator landscape! Armed with this knowledge, you can now confidently navigate the sometimes-bewildering world of economic data. Remember, while these indicators offer valuable insights, they are not foolproof. The economy, like a mischievous toddler, often surprises us. But with a healthy dose of understanding and a dash of humor, we can face the future with a little more financial flair. Happy forecasting!

General Inquiries

What’s the difference between nominal and real GDP?

Nominal GDP is calculated using current prices, while real GDP adjusts for inflation, providing a more accurate picture of economic growth.

How is the unemployment rate calculated?

It’s the percentage of the labor force (employed plus unemployed) that is actively seeking work but unable to find it.

What are some limitations of using CPI as a measure of inflation?

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) may not fully capture changes in the quality of goods and services, or shifts in consumer spending habits.

How do interest rate changes affect the stock market?

Higher interest rates generally lead to lower stock prices as investors shift to higher-yielding bonds, while lower rates can boost stock prices.