Understanding a company’s financial health is crucial for informed decision-making, whether you’re an investor, creditor, or manager. Analisis Keuangan, or financial statement analysis, provides the tools and techniques to dissect a company’s financial performance, assess its risks, and predict its future trajectory. This guide delves into the core principles of financial statement analysis, equipping you with the knowledge to interpret financial statements and make data-driven judgments.

We will explore various analytical methods, from ratio analysis and trend analysis to cash flow analysis and comparative benchmarking. By examining key financial statements – the balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement – we’ll uncover valuable insights into a company’s liquidity, profitability, solvency, and overall financial health. We will also address the limitations of financial analysis and the importance of considering qualitative factors alongside quantitative data for a holistic understanding.

Introduction to Financial Statement Analysis

Financial statement analysis is a crucial process for making informed decisions in various contexts, from assessing a company’s performance and financial health to guiding investment strategies and creditworthiness evaluations. Understanding the financial picture of an entity, whether a corporation, small business, or even a personal financial portfolio, hinges on the ability to effectively analyze financial statements. This analysis allows stakeholders to identify trends, assess risks, and make predictions about future performance.

Financial statement analysis involves systematically examining a company’s financial statements to gain insights into its financial position, performance, and cash flows. These insights are then used to make critical judgments about the entity’s viability, profitability, and overall health. Effective analysis relies not only on understanding the individual statements but also on interpreting the relationships between them, providing a holistic view of the financial picture.

Types of Financial Statements Used in Analysis

The primary financial statements used in analysis are the balance sheet, the income statement, and the cash flow statement. Each provides a unique perspective on the financial state of an entity, and a comprehensive analysis requires examining all three.

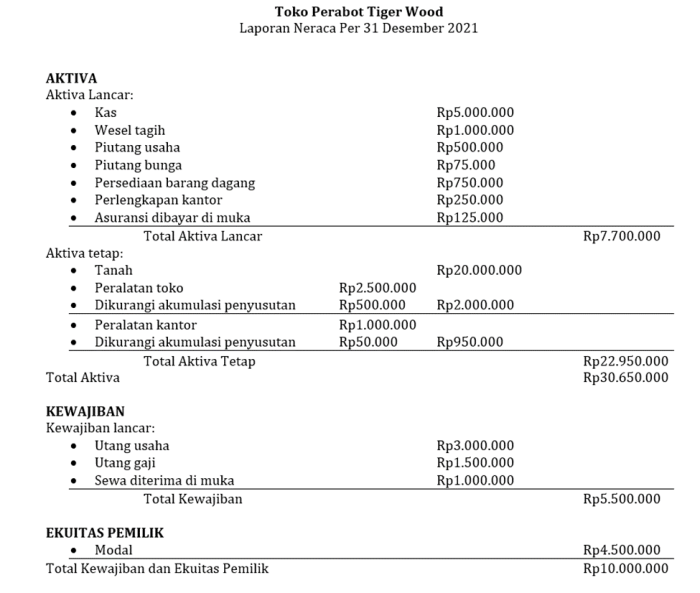

The balance sheet presents a snapshot of a company’s assets, liabilities, and equity at a specific point in time. It follows the fundamental accounting equation: Assets = Liabilities + Equity. Analyzing the balance sheet reveals information about the company’s liquidity, solvency, and capital structure. For example, a high ratio of current assets to current liabilities suggests strong short-term liquidity.

The income statement, also known as the profit and loss statement, summarizes a company’s revenues and expenses over a specific period. It shows the company’s profitability, highlighting key metrics like gross profit, operating income, and net income. Analyzing the income statement helps assess the company’s operational efficiency and pricing strategies. A consistent increase in net income year over year indicates strong profitability.

The cash flow statement tracks the movement of cash both into and out of a company over a specific period. It categorizes cash flows into operating activities, investing activities, and financing activities. Analyzing the cash flow statement provides crucial insights into the company’s ability to generate cash, manage its debt, and fund its operations. A positive cash flow from operations demonstrates the company’s ability to generate cash from its core business activities.

Obtaining and Preparing Financial Statements for Analysis

The process of obtaining and preparing financial statements for analysis involves several key steps. First, the relevant financial statements must be sourced. For publicly traded companies, these are readily available through regulatory filings (like the SEC’s EDGAR database in the US) and company websites. For privately held companies, obtaining statements may require direct requests to the company.

Once obtained, the statements should be reviewed for completeness and accuracy. Any inconsistencies or unusual entries should be investigated. This may involve contacting the company or consulting with accounting professionals. Next, the financial statements should be prepared for analysis. This might involve adjusting the statements for accounting differences or inconsistencies, recalculating key ratios, and creating comparative analyses across different periods. For example, calculating the current ratio (Current Assets / Current Liabilities) and comparing it to industry averages helps assess liquidity.

Finally, the analyst should select appropriate analytical tools and techniques to interpret the data. This might involve ratio analysis, trend analysis, or comparative analysis with industry benchmarks. The results of the analysis should be documented and presented clearly, highlighting key findings and insights. For example, a trend analysis of revenue growth over several years can reveal important information about the company’s market position and growth prospects. Using these steps ensures a thorough and reliable analysis.

Ratio Analysis Techniques

Ratio analysis is a crucial tool in financial statement analysis, providing insights into a company’s performance, financial health, and operational efficiency. By calculating and interpreting various ratios, analysts can assess a company’s liquidity, solvency, profitability, and efficiency, ultimately informing investment decisions and strategic planning. This section delves into the different categories of financial ratios and illustrates their application with examples.

Liquidity Ratios

Liquidity ratios measure a company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations. These ratios are vital for assessing the immediate financial health of a business and its capacity to pay off debts that are due within a year. A company with strong liquidity is less likely to face financial distress.

Key liquidity ratios include the Current Ratio and the Quick Ratio. The Current Ratio is calculated by dividing current assets by current liabilities:

Current Ratio = Current Assets / Current Liabilities

. A current ratio of 2.0, for instance, suggests that a company has twice the amount of current assets as current liabilities, indicating a strong ability to meet short-term obligations. The Quick Ratio, also known as the acid-test ratio, provides a more conservative measure of liquidity by excluding inventory from current assets:

Quick Ratio = (Current Assets – Inventory) / Current Liabilities

. A higher quick ratio indicates a stronger ability to meet short-term obligations even without relying on the sale of inventory.

Solvency Ratios

Solvency ratios gauge a company’s ability to meet its long-term obligations and its overall financial stability. These ratios are essential for understanding a company’s long-term financial health and its capacity to survive potential economic downturns or financial crises. Investors and creditors use solvency ratios to assess the risk of default.

Examples of key solvency ratios include the Debt-to-Equity Ratio and the Times Interest Earned Ratio. The Debt-to-Equity Ratio measures the proportion of a company’s financing that comes from debt relative to equity:

Debt-to-Equity Ratio = Total Debt / Total Equity

. A high debt-to-equity ratio suggests a higher reliance on debt financing, potentially increasing financial risk. The Times Interest Earned Ratio assesses a company’s ability to cover its interest expenses with its earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT):

Times Interest Earned Ratio = EBIT / Interest Expense

. A higher ratio indicates a stronger ability to meet interest obligations.

Profitability Ratios

Profitability ratios measure a company’s ability to generate profits from its operations. These ratios are critical for evaluating the efficiency and effectiveness of a company’s business model and its ability to create value for its shareholders. Investors often use profitability ratios to compare the performance of different companies within the same industry.

Important profitability ratios include Gross Profit Margin, Net Profit Margin, and Return on Equity (ROE). The Gross Profit Margin shows the profitability of sales after deducting the cost of goods sold:

Gross Profit Margin = (Revenue – Cost of Goods Sold) / Revenue

. The Net Profit Margin indicates the percentage of revenue that remains as profit after all expenses are deducted:

Net Profit Margin = Net Income / Revenue

. Finally, Return on Equity (ROE) measures the return generated on the shareholders’ investment:

Return on Equity (ROE) = Net Income / Shareholder’s Equity

.

Efficiency Ratios

Efficiency ratios, also known as activity ratios, evaluate how effectively a company manages its assets and liabilities to generate sales and profits. These ratios provide insights into operational efficiency and the effectiveness of resource utilization. Improving efficiency ratios often leads to enhanced profitability.

Key efficiency ratios include Inventory Turnover, Accounts Receivable Turnover, and Asset Turnover. Inventory Turnover measures how efficiently a company manages its inventory:

Inventory Turnover = Cost of Goods Sold / Average Inventory

. A high inventory turnover suggests efficient inventory management. Accounts Receivable Turnover indicates how quickly a company collects its receivables:

Accounts Receivable Turnover = Net Credit Sales / Average Accounts Receivable

. A higher turnover implies faster collection of receivables. Asset Turnover measures how effectively a company uses its assets to generate sales:

Asset Turnover = Revenue / Average Total Assets

. A higher asset turnover ratio suggests efficient utilization of assets.

Comparison of Ratio Analysis Methods

| Ratio Name | Formula | Interpretation | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Ratio | Current Assets / Current Liabilities | Measures short-term liquidity; higher is generally better. | A current ratio of 2.0 indicates that a company has twice the amount of current assets as current liabilities. |

| Debt-to-Equity Ratio | Total Debt / Total Equity | Measures the proportion of debt financing; lower is generally preferred. | A debt-to-equity ratio of 0.5 suggests that a company has half as much debt as equity. |

| Net Profit Margin | Net Income / Revenue | Measures profitability relative to revenue; higher is better. | A net profit margin of 10% indicates that 10% of revenue remains as profit after all expenses. |

| Inventory Turnover | Cost of Goods Sold / Average Inventory | Measures how efficiently inventory is managed; higher is generally better. | An inventory turnover of 5 indicates that the company sells and replaces its inventory five times a year. |

Trend Analysis and Forecasting

Trend analysis in financial statement analysis involves examining historical financial data to identify patterns and predict future performance. This process provides valuable insights for decision-making, allowing businesses to anticipate challenges and capitalize on opportunities. By understanding past trends, companies can make more informed strategic choices, allocate resources effectively, and improve overall financial health.

Trend analysis utilizes historical data from financial statements such as income statements, balance sheets, and cash flow statements. These data points are typically plotted over time to visually represent the trends. Forecasting, on the other hand, builds upon the identified trends to project future financial performance. Accurate forecasting requires careful consideration of both internal and external factors that might influence the company’s future.

Conducting Trend Analysis Using Historical Financial Data

Trend analysis begins with gathering relevant historical financial data. This usually spans several years, ideally five or more, to capture meaningful patterns. The data is then organized and presented in a clear format, often a table or spreadsheet. Common metrics analyzed include revenue, net income, expenses, assets, liabilities, and equity. Percentage changes year-over-year are calculated to highlight the growth or decline in these metrics. For instance, a company can calculate the percentage change in revenue from one year to the next, revealing the growth rate. Significant deviations from the established trend should be investigated to understand the underlying causes.

Forecasting Future Financial Performance Based on Identified Trends

Several methods exist for forecasting future financial performance. One common approach is linear regression, which assumes a linear relationship between the dependent variable (e.g., revenue) and the independent variable (time). The regression model provides an equation that can be used to predict future values. Another approach is using moving averages, where the average of the past few periods is used to predict the next period. Exponential smoothing, a more sophisticated method, assigns exponentially decreasing weights to older data points, giving more importance to recent data. The choice of method depends on the nature of the data and the desired level of accuracy. For example, a company experiencing rapid growth might use a method that emphasizes recent data, while a company with stable performance might use a simpler moving average.

Visual Representation of Trend Analysis Using Charts and Graphs

Visual representations are crucial for understanding and communicating trend analysis findings. Line graphs are particularly effective for showing trends over time. A line graph depicting revenue over five years, for example, would show a line connecting data points for each year. The slope of the line indicates the rate of growth or decline. A bar chart can also be used to compare financial metrics across different periods. For instance, a bar chart could compare net income for each year, with each bar representing a year’s net income. The height of each bar visually represents the magnitude of the net income for that specific year. A combination chart might overlay a line graph of revenue growth on top of a bar chart of net income, facilitating a comparison of these two important metrics. For example, this would show whether increases in revenue translate directly into increases in net income, allowing analysis of profitability.

Cash Flow Analysis

Cash flow analysis is a crucial aspect of financial statement analysis, providing insights into a company’s ability to generate cash, manage its liquidity, and fund its operations and growth. Unlike accrual-based accounting, which recognizes revenue and expenses when earned or incurred, cash flow statements focus solely on the actual inflows and outflows of cash. This direct focus on cash makes it a valuable tool for assessing a company’s financial health and predicting its future performance.

Understanding the cash flow statement is essential for investors, creditors, and management alike. It offers a clearer picture of a company’s financial reality than the income statement or balance sheet alone, helping stakeholders make informed decisions about investments, lending, and operational strategies.

Key Components of a Cash Flow Statement and Their Significance

The cash flow statement is divided into three main sections: operating activities, investing activities, and financing activities. Each section provides critical information about different aspects of a company’s cash management. Operating activities reflect the cash generated or used in the core business operations. Investing activities relate to the acquisition and disposal of long-term assets. Financing activities encompass how the company raises and uses capital. Analyzing each section separately and in conjunction with the others provides a comprehensive understanding of a company’s cash flow dynamics. For example, strong operating cash flow indicates a healthy and profitable business, while significant investing activities might suggest expansion or restructuring. Conversely, relying heavily on financing activities for cash flow could indicate financial instability.

Comparison of Direct and Indirect Methods of Preparing a Cash Flow Statement

There are two primary methods for preparing the cash flow statement: the direct method and the indirect method. The direct method directly tracks cash inflows and outflows from operating activities, providing a clear and straightforward picture of cash generated from core operations. The indirect method, on the other hand, starts with net income and adjusts it for non-cash items and changes in working capital to arrive at cash flow from operating activities. While both methods ultimately arrive at the same net cash flow, the direct method offers a more transparent view of operating cash flows, whereas the indirect method provides more information about the relationship between net income and cash flow. Many companies use the indirect method due to its relative simplicity and reliance on readily available data from the income statement and balance sheet.

Analysis of Cash Flow from Operating, Investing, and Financing Activities

Analyzing cash flow from each activity provides a holistic view of a company’s financial health. Strong positive cash flow from operating activities signifies a healthy business generating sufficient cash from its core operations. This is a key indicator of financial strength and sustainability. Analyzing investing activities reveals a company’s capital expenditure strategies. Significant capital expenditures suggest investment in growth, while disposals might signal restructuring or a shift in business focus. Finally, examining financing activities helps assess a company’s reliance on debt or equity financing. Consistent reliance on debt financing could raise concerns about financial risk, while increased equity financing suggests a more conservative approach. For example, a company with strong operating cash flow, moderate investing activities, and limited reliance on debt financing generally demonstrates a robust financial position. Conversely, a company with weak operating cash flow, high capital expenditures financed primarily by debt, might indicate financial instability and potential risks.

Analyzing Financial Health and Risk

Assessing a company’s financial health and risk involves a multifaceted approach, going beyond simply reviewing profitability. It requires a deep dive into various financial statements and ratios to understand the company’s liquidity, solvency, and operational efficiency, ultimately providing a comprehensive picture of its financial stability and potential for future success or failure. This analysis is crucial for investors, creditors, and management alike in making informed decisions.

Understanding the key indicators of financial distress and their implications is vital for proactive risk management. A company’s financial health is not static; it’s a dynamic interplay of various factors, and identifying potential problems early can prevent significant future losses. This section explores the methodologies used to assess these risks and the signals that indicate a company may be heading towards financial distress.

Methods for Assessing Financial Health and Risk

Several methods exist for evaluating a company’s financial health and risk profile. These include analyzing financial ratios, such as liquidity ratios (current ratio, quick ratio), solvency ratios (debt-to-equity ratio, times interest earned), and profitability ratios (gross profit margin, net profit margin). Trend analysis, examining changes in these ratios over time, provides valuable insights into the company’s performance trajectory. Cash flow analysis, focusing on the inflows and outflows of cash, is another critical method, revealing the company’s ability to meet its short-term and long-term obligations. Furthermore, comparative analysis, comparing a company’s financial performance to its industry peers, offers a benchmark for assessing its relative strength and weakness. Finally, using financial modeling techniques can help predict future performance and identify potential vulnerabilities. For example, a sensitivity analysis can show how changes in key variables (e.g., sales volume, interest rates) might affect the company’s financial position.

Key Indicators of Financial Distress

Several key indicators signal potential financial distress. A declining current ratio suggests a weakening ability to meet short-term obligations. A high debt-to-equity ratio indicates heavy reliance on debt financing, increasing financial risk. Consistently low or negative cash flows from operations are a major red flag, signifying difficulties in generating cash from core business activities. A deteriorating profit margin points to declining profitability and potential operational inefficiencies. Furthermore, increasing days sales outstanding (DSO) suggests problems with collecting receivables, which can strain liquidity. Finally, a significant decline in sales or market share can signal underlying problems that could lead to financial distress. For instance, a company like Blockbuster experienced a sharp decline in sales and market share due to the rise of streaming services, ultimately leading to its bankruptcy.

Evaluating the Creditworthiness of a Business

Evaluating the creditworthiness of a business involves a systematic approach, considering various financial and non-financial factors.

- Reviewing Financial Statements: A thorough examination of the balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement is paramount. This includes analyzing key ratios like those mentioned above.

- Assessing Management Quality: Evaluating the experience, competence, and integrity of the management team is crucial. A strong management team is more likely to navigate financial challenges effectively.

- Analyzing Industry Conditions: Understanding the industry’s overall health and competitive landscape is essential. A struggling industry can negatively impact even well-managed businesses.

- Considering Collateral: The availability of collateral (assets that can be used to secure a loan) significantly influences creditworthiness. Businesses with substantial assets are generally considered less risky.

- Investigating Legal and Regulatory Compliance: Ensuring the business operates within legal and regulatory frameworks minimizes potential financial and legal risks.

- Checking Credit History: Reviewing the business’s past credit performance provides valuable insights into its repayment behavior.

Comparative Analysis

Comparative analysis provides a crucial perspective on a company’s financial performance by placing it within the context of its industry peers. This allows for a more nuanced understanding of its strengths and weaknesses, identifying areas for improvement and opportunities for growth. By benchmarking against competitors, companies can assess their efficiency, profitability, and overall financial health relative to the market.

Benchmarking techniques are essential tools in comparative analysis. These techniques involve comparing a company’s financial ratios and performance metrics against those of its competitors, industry averages, or best-in-class organizations. This comparison facilitates the identification of best practices and areas where improvements can be made.

Benchmarking Techniques

Several methods are used for benchmarking. These approaches allow for a comprehensive assessment across different aspects of financial performance. Selecting the appropriate technique depends on the specific goals of the analysis and the availability of data.

- Industry Average Comparison: This involves comparing a company’s financial ratios (e.g., profitability, liquidity, solvency) to the average ratios of its industry peers. Industry averages can be obtained from industry reports, financial databases (like Bloomberg or Refinitiv), and government publications. For example, comparing a retail company’s inventory turnover ratio to the average inventory turnover ratio for the retail industry provides insight into its inventory management efficiency.

- Competitor-Specific Comparison: This involves directly comparing a company’s financial performance to that of its key competitors. This provides a more targeted assessment of relative performance and competitive positioning. For instance, comparing a pharmaceutical company’s research and development spending as a percentage of revenue to that of its direct competitors reveals insights into its investment in innovation relative to the market.

- Best-in-Class Benchmarking: This method involves comparing a company’s performance to that of the best-performing companies in its industry or even across industries. This helps identify best practices and areas for improvement. Imagine comparing a manufacturing company’s operational efficiency (measured by metrics like production output per employee) to that of the most efficient manufacturer in the world, regardless of industry. This reveals potential areas for significant improvement.

Identifying Areas of Strength and Weakness

Comparative analysis facilitates the identification of areas where a company excels or lags behind its competitors. By systematically comparing key financial metrics, businesses can gain valuable insights into their competitive advantages and disadvantages.

For example, a higher-than-average profit margin indicates a strong competitive advantage, possibly due to superior pricing power, efficient cost management, or a unique product offering. Conversely, a lower-than-average return on assets (ROA) might signal inefficiencies in asset utilization or weak profitability, suggesting areas requiring improvement. Analyzing trends in these metrics over time provides further insights into the sustainability of these strengths and weaknesses. A consistent pattern of underperformance in a specific area warrants a more in-depth investigation into the underlying causes. This investigation might involve reviewing operational processes, examining market conditions, and assessing the effectiveness of the company’s strategic initiatives.

Limitations of Financial Statement Analysis

Financial statement analysis, while a powerful tool for evaluating a company’s financial health, is not without its limitations. The information presented is inherently backward-looking, offering a snapshot of past performance rather than a crystal ball for future prospects. Furthermore, the analysis relies heavily on the accuracy and consistency of the accounting methods employed, which can be subject to manipulation or simply reflect different interpretations of accounting standards. Understanding these limitations is crucial for drawing informed conclusions and avoiding potentially misleading interpretations.

The inherent limitations and potential biases in financial statement analysis stem from several key factors. Firstly, the data itself is subject to manipulation, either intentionally through fraudulent reporting or unintentionally through errors in recording or processing. Secondly, the accounting principles used can vary between companies and across different jurisdictions, making direct comparisons challenging. Finally, the financial statements only reflect the quantitative aspects of a business; they fail to capture the qualitative factors that can significantly impact its performance and long-term viability.

Accounting Practices and Methods

Different accounting methods can significantly impact reported financial figures. For instance, the choice between LIFO (Last-In, First-Out) and FIFO (First-In, First-Out) inventory valuation methods can affect the cost of goods sold and ultimately the reported net income. A company choosing LIFO during a period of inflation will report higher costs and lower profits than a company using FIFO, even if both companies have identical operations. Similarly, variations in depreciation methods can significantly alter the reported value of assets and profitability over time. This lack of standardization makes direct comparisons between companies using different accounting methods problematic.

Qualitative Factors

The limitations of relying solely on quantitative data from financial statements are significant. Qualitative factors, such as management quality, employee morale, brand reputation, and competitive landscape, are often overlooked but can profoundly impact a company’s success. For example, a company with strong financial ratios might be facing a significant threat from a new disruptive technology, a fact not apparent in its financial statements. Conversely, a company with seemingly weak financial performance might be undergoing a successful restructuring that will yield positive results in the future. Ignoring these qualitative aspects leads to an incomplete and potentially misleading assessment of the company’s overall health.

Examples of Misleading Financial Statement Analysis

Several scenarios illustrate how financial statement analysis can be misleading or insufficient. A company might appear highly profitable based on its net income, but a closer examination of its cash flow statement reveals significant cash burn, indicating a potentially unsustainable business model. Similarly, a company with high debt levels might appear solvent based on its balance sheet alone, but the interest expense associated with that debt could be crippling its profitability. Furthermore, aggressive accounting practices, such as overstating revenue or understating expenses, can paint a rosier picture than reality, potentially masking underlying financial weaknesses until it’s too late. A classic example is the Enron scandal, where sophisticated accounting manipulations concealed significant debt and losses, leading to the company’s eventual collapse.

Final Conclusion

Mastering Analisis Keuangan is not merely about crunching numbers; it’s about gaining a deep understanding of a company’s financial story. By applying the techniques discussed – from interpreting ratios and analyzing trends to assessing cash flow and conducting comparative analyses – you can confidently evaluate financial performance, identify potential risks and opportunities, and make informed decisions based on solid financial data. Remember that while quantitative analysis is essential, integrating qualitative factors will provide a more complete and accurate picture of a company’s financial health.

Key Questions Answered

What is the difference between liquidity and solvency ratios?

Liquidity ratios measure a company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations, while solvency ratios assess its ability to meet its long-term obligations.

How can I find financial statements for public companies?

Public companies are required to file their financial statements with regulatory bodies like the SEC (in the US). These filings are usually accessible through the company’s investor relations website or the regulatory body’s website.

What are some common qualitative factors to consider in financial statement analysis?

Qualitative factors include management quality, industry trends, competitive landscape, regulatory environment, and overall economic conditions.

What are the limitations of using only historical financial data for forecasting?

Historical data may not accurately reflect future performance due to unforeseen circumstances, changes in market conditions, or strategic shifts within the company.