Understanding economic indicators is crucial for navigating the complexities of the global economy. These vital metrics offer insights into past, present, and future economic performance, allowing businesses, governments, and individuals to make informed decisions. From tracking GDP growth to analyzing inflation rates and unemployment figures, mastering economic indicators empowers a deeper understanding of economic trends and their potential impact.

This guide provides a comprehensive overview of key macroeconomic indicators, exploring their calculation methods, implications, and limitations. We will delve into the differences between leading, lagging, and coincident indicators, demonstrating how they contribute to a holistic understanding of economic cycles. Furthermore, we’ll explore how businesses utilize this data for strategic planning and decision-making, highlighting the importance of interpreting economic data accurately and effectively.

Introduction to Economic Indicators

Economic indicators are crucial tools for understanding the overall health and performance of an economy. They provide a snapshot of various economic activities, allowing economists, policymakers, and businesses to track trends, anticipate future developments, and make informed decisions. By analyzing these indicators, we can gain valuable insights into the current state of the economy and predict potential shifts in the near future. This understanding is essential for effective economic planning and policy-making.

The Purpose of Economic Indicators

Economic indicators serve a multitude of purposes. Primarily, they help us gauge the overall performance of an economy. They provide quantifiable data on key aspects such as production, employment, consumer spending, and inflation. This data is then used to assess economic growth, identify potential problems, and evaluate the effectiveness of government policies. For instance, a sustained decline in GDP growth might signal a recession, prompting policymakers to implement stimulus measures. Conversely, rising inflation might necessitate measures to control price increases.

Classification of Economic Indicators by Timing

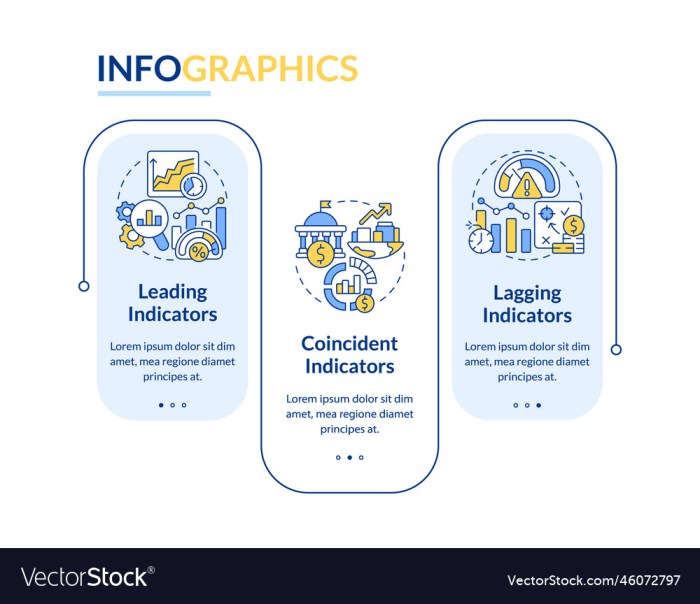

Economic indicators are broadly categorized based on their timing relative to economic fluctuations: leading, lagging, and coincident. Leading indicators tend to change *before* the overall economy changes direction, offering early warnings of potential booms or busts. Lagging indicators, on the other hand, change *after* the economy has already shifted, confirming the trend. Coincident indicators move *at the same time* as the overall economy, providing a current picture of economic activity. Understanding these timing differences is critical for accurate economic forecasting and informed decision-making.

Examples of Economic Indicators Across Sectors

Several key indicators provide insights into different economic sectors. In the manufacturing sector, the Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) is a widely used leading indicator reflecting the activity levels of purchasing managers in the manufacturing industry. A PMI above 50 generally suggests expansion, while a reading below 50 indicates contraction. Within the employment sector, the unemployment rate, a lagging indicator, measures the percentage of the labor force that is unemployed and actively seeking work. This indicator provides a crucial insight into the health of the labor market. Finally, consumer spending, a coincident indicator, as measured by retail sales figures, reflects consumer confidence and spending patterns, providing a valuable insight into the overall health of the economy. Strong consumer spending typically indicates a healthy economy, while weak spending can be a warning sign of economic slowdown.

Key Macroeconomic Indicators

Understanding key macroeconomic indicators is crucial for assessing the overall health and performance of an economy. These indicators provide insights into various aspects, from production and employment to price stability and overall economic growth. Analyzing these indicators helps policymakers, businesses, and individuals make informed decisions.

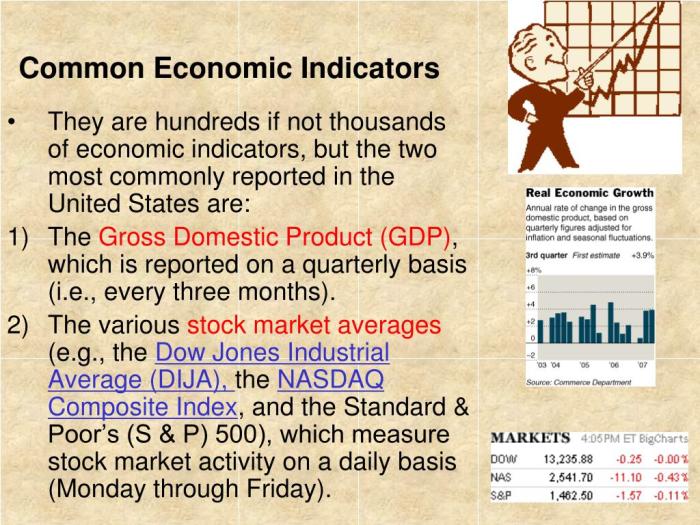

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and its Components

GDP, the total monetary or market value of all the finished goods and services produced within a country’s borders in a specific time period, is calculated using several methods, all aiming to arrive at the same figure. The expenditure approach sums up all spending on final goods and services within the economy. This includes consumption (C), investment (I), government spending (G), and net exports (NX), which is exports (X) minus imports (M). The formula is:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

. The income approach calculates GDP by summing up all the incomes earned in producing those goods and services, including wages, profits, rents, and interest. Finally, the production approach adds up the value added at each stage of production for all goods and services. While different in approach, these methods ideally converge to the same final GDP figure.

Implications of Changes in Inflation Rates (CPI, PPI)

Inflation, a general increase in the price level of goods and services in an economy over a period of time, significantly impacts economic stability. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) measures the average change in prices paid by urban consumers for a basket of consumer goods and services. The Producer Price Index (PPI) tracks the average change in prices received by domestic producers for their output. Rising inflation erodes purchasing power, potentially leading to decreased consumer spending and economic slowdown. High and unpredictable inflation can also destabilize financial markets and create uncertainty for businesses and investors. Conversely, deflation, a sustained decrease in the general price level, can also be problematic, potentially leading to decreased investment and economic stagnation as consumers postpone purchases anticipating further price drops. Central banks often use monetary policy tools, like interest rate adjustments, to manage inflation and maintain price stability.

Significance of Unemployment Rates and their Impact on the Labor Market

The unemployment rate, the percentage of the labor force that is actively seeking employment but unable to find it, is a critical indicator of labor market health. A high unemployment rate signals economic weakness, potentially leading to decreased consumer spending and social unrest. It indicates a mismatch between the available jobs and the skills of the unemployed workforce. Conversely, a low unemployment rate often suggests a strong economy with high demand for labor, potentially leading to wage increases and increased consumer spending. However, extremely low unemployment can also lead to inflationary pressures as businesses compete for a limited pool of workers. Different types of unemployment exist, including frictional (temporary unemployment between jobs), structural (mismatch between skills and job availability), and cyclical (due to economic downturns). Understanding the causes and types of unemployment is vital for effective policy responses.

Comparison of Different Measures of Inflation

Several measures exist to gauge inflation, each with its strengths and limitations. The CPI, as mentioned, focuses on consumer prices. The PPI focuses on producer prices, offering an early warning signal of potential future consumer price inflation. The GDP deflator, which adjusts nominal GDP for inflation, provides a broader measure encompassing all goods and services produced within the economy. While all aim to measure price changes, differences in the basket of goods and services considered, weighting methodologies, and data collection techniques can lead to variations in the reported inflation rates. Understanding these differences is crucial for interpreting inflation data accurately.

GDP Growth Rates Across Different Countries

The following table compares GDP growth rates (annual percentage change) for selected countries over the past five years. Note that these figures are estimates and may vary slightly depending on the source and methodology used. (Data would be sourced from reputable organizations like the World Bank or IMF and inserted here.)

| Country | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | Year 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 2.0% | 2.5% | 1.8% | 3.0% | 2.2% |

| China | 6.5% | 6.0% | 6.2% | 6.8% | 6.1% |

| Germany | 1.5% | 1.0% | 0.5% | 1.2% | 1.8% |

| Japan | 1.0% | 0.8% | 0.5% | 1.1% | 1.3% |

Analyzing Leading Indicators

Leading economic indicators are crucial tools for forecasting future economic activity. They provide insights into the direction the economy is heading, allowing businesses and policymakers to make informed decisions. While not perfectly predictive, their analysis offers valuable early warnings of potential economic booms or downturns.

Three Leading Economic Indicators and Their Predictive Power

Three prominent leading indicators offer valuable insights into future economic trends. These indicators, while not foolproof, provide a strong indication of potential future economic performance. Understanding their predictive power is vital for effective economic planning.

- Consumer Confidence Index: This index gauges consumer sentiment regarding the current and future economic situation. High consumer confidence suggests increased spending and investment, fueling economic growth. Conversely, low confidence indicates reduced spending and investment, potentially leading to a slowdown. The predictive power stems from the direct link between consumer spending and overall economic activity; consumer spending constitutes a significant portion of GDP. A sharp decline in consumer confidence often precedes a recession.

- Building Permits: The number of building permits issued serves as a proxy for future construction activity. An increase in building permits suggests anticipated growth in the construction sector, creating jobs and boosting economic activity. This indicator’s predictive power is based on the time lag between permit issuance and actual construction. The increase in permits signals upcoming investments and subsequent economic expansion, albeit with a time delay.

- Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI): This index tracks the activity of purchasing managers in the manufacturing sector. A PMI above 50 indicates expansion, while a reading below 50 signals contraction. The predictive power of the PMI lies in its sensitivity to changes in demand and production. A sustained decline in the PMI often foreshadows a broader economic slowdown, as manufacturing activity is a significant driver of overall economic output.

Scenario: Consumer Confidence and Economic Growth

Imagine a scenario where a sudden surge in oil prices causes widespread inflation. Consumers, facing higher prices for essential goods and services, become increasingly pessimistic about their future financial prospects. This leads to a sharp decline in the Consumer Confidence Index. As a result, consumers postpone major purchases like cars and houses, and reduce discretionary spending on entertainment and travel. Businesses, sensing reduced consumer demand, cut back on investment and hiring. This decrease in consumer spending and business investment ultimately leads to a slowdown in economic growth, potentially even a recession. The initial drop in consumer confidence acted as a leading indicator of this economic downturn.

Limitations of Leading Indicators for Economic Forecasting

While leading indicators offer valuable insights, it’s crucial to acknowledge their limitations. They are not perfect predictors, and their accuracy can be affected by various factors.

- Unforeseen Events: Unexpected events, such as natural disasters, geopolitical crises, or technological disruptions, can significantly impact the economy in ways that leading indicators may not fully capture. The COVID-19 pandemic, for example, caused a sudden and sharp economic downturn that was not fully predicted by leading indicators.

- Data Revisions: Economic data is often revised as more information becomes available. Initial readings of leading indicators may be inaccurate or incomplete, leading to flawed predictions. This revision process can sometimes significantly alter the initial interpretation of the indicators.

- False Signals: Leading indicators can sometimes give false signals, suggesting an economic boom or bust that doesn’t materialize. This can occur due to temporary fluctuations in the data or unforeseen changes in economic conditions. Over-reliance on a single indicator, without considering other economic factors, can lead to misinterpretations.

Interpreting Lagging Indicators

Lagging indicators, unlike their leading counterparts, don’t predict future economic activity; instead, they confirm trends that have already occurred. They provide valuable insights into the past performance of the economy and help to assess the effectiveness of previous economic policies. Understanding lagging indicators is crucial for a complete picture of economic health and for making informed decisions about future strategies.

Lagging indicators act as a retrospective confirmation of the economic climate. They typically show changes in economic activity after a significant period has passed. This delay provides a clearer, more comprehensive view of the actual impact of economic shifts, allowing for a more accurate assessment of the overall economic situation. By analyzing these indicators, economists can better understand the duration and intensity of economic expansions and contractions, informing future policy decisions and business strategies.

Examples of Lagging Indicators and Their Relationship to Business Cycles

Several key indicators fall into the lagging category. These indicators typically reflect changes in the economy after a significant period, often several months or even quarters. Their delayed response provides a more comprehensive and accurate understanding of the economic climate, confirming trends revealed by leading indicators.

For example, the unemployment rate often rises after a recession has begun and falls after the economy has started to recover. This is because businesses typically don’t immediately lay off workers when economic conditions worsen, and similarly, they don’t immediately hire more workers when conditions improve. There’s a time lag built into employment decisions.

Another example is the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for inflation. While inflation can be influenced by leading indicators such as commodity prices, the official CPI figures lag behind the actual inflationary pressures. This lag is due to the time required to collect and process the vast amount of data necessary to calculate the index. Similarly, changes in average manufacturing wage rates typically follow changes in productivity and employment.

The relationship between these lagging indicators and business cycles is clear. During an economic expansion, these indicators will generally show improvement, confirming the positive trend. Conversely, during a recession, they will reflect the negative impacts of the downturn. This lagged response allows economists to analyze the depth and duration of the economic cycle with greater certainty than leading indicators alone would allow.

Using Lagging Indicators to Assess Economic Policy Effectiveness

Lagging indicators play a vital role in evaluating the success or failure of past economic policies. By observing their response to policy interventions, policymakers can gain valuable feedback and refine their approaches for future challenges.

For instance, if the government implemented a stimulus package aimed at boosting employment, lagging indicators such as the unemployment rate and average manufacturing wage rates would provide crucial data points to assess the policy’s effectiveness. A significant decline in the unemployment rate several months after the stimulus would suggest a successful intervention. Conversely, if the unemployment rate remained stagnant or increased, it would indicate that the policy was less effective than anticipated, prompting a reassessment of the approach.

Similarly, if a central bank implemented a monetary policy aimed at controlling inflation, the CPI would serve as a key lagging indicator to assess the policy’s impact. A sustained decline in the CPI several months after the policy implementation would suggest its success in curbing inflation. Conversely, a persistent or accelerating inflation rate would suggest the policy’s ineffectiveness and require further adjustments.

The use of lagging indicators in this way is crucial for evidence-based policymaking. It allows policymakers to learn from past experiences, refine their strategies, and improve their ability to manage the economy effectively. It provides the necessary retrospective analysis that helps to create more robust and effective economic policies in the future.

Understanding Coincident Indicators

Coincident indicators offer a real-time snapshot of the current economic situation. Unlike leading indicators which predict future trends, or lagging indicators which confirm past performance, coincident indicators provide a contemporaneous view, allowing economists and policymakers to gauge the economy’s present health. This understanding is crucial for informed decision-making and effective policy adjustments.

Coincident indicators track various aspects of economic activity simultaneously, providing a more comprehensive picture than any single indicator could offer. By analyzing these indicators together, a clearer understanding of the economy’s current state emerges, allowing for a more nuanced interpretation than any individual metric could provide.

Examples of Coincident Indicators and Their Insights

Several key indicators provide real-time insights into economic performance. For example, the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is a comprehensive measure of the total value of goods and services produced within a country’s borders during a specific period. A rising GDP generally signals economic expansion, while a declining GDP suggests a contraction. Similarly, employment figures, such as the unemployment rate, provide crucial information about the labor market’s health. A low unemployment rate usually correlates with economic strength, whereas a high unemployment rate points towards economic weakness. Industrial production indices, which track the output of factories and mines, also offer valuable insights into the manufacturing sector’s performance and overall economic activity. Finally, personal income and personal consumption expenditures (PCE) provide insights into consumer spending and overall economic demand. A surge in these figures indicates increased consumer confidence and robust economic activity. Analyzing these indicators concurrently allows for a holistic assessment of the current economic climate.

The Role of Coincident Indicators in Policy Decision-Making

Coincident indicators play a vital role in informing policy decisions at both the national and international levels. Central banks, for instance, use coincident indicators like inflation rates (measured by the Consumer Price Index or CPI) and GDP growth to adjust monetary policy. High inflation might prompt an increase in interest rates to curb inflation, while slow growth might necessitate a reduction in interest rates to stimulate economic activity. Governments also rely on these indicators to guide fiscal policy decisions. For example, a sharp rise in unemployment might lead to the implementation of job creation programs or increased social welfare spending. In essence, coincident indicators act as crucial guideposts for policymakers, allowing them to react promptly and effectively to changing economic conditions.

Tracking the Current State of the Economy with Coincident Indicators

Coincident indicators are essential tools for tracking the current economic situation. By monitoring these indicators regularly, economists and policymakers can identify shifts in economic momentum, assess the effectiveness of implemented policies, and make informed predictions about future trends, albeit with a limited predictive capacity compared to leading indicators. For instance, a sustained increase in GDP, coupled with a low unemployment rate and strong industrial production, would strongly suggest a healthy and expanding economy. Conversely, a simultaneous decline in these indicators would paint a picture of economic contraction or recession. The combined analysis of these indicators offers a far more nuanced and reliable assessment of the current economic health than any single indicator could provide.

Visualizing Economic Data

Effective visualization is crucial for understanding complex economic relationships. Graphs and charts transform raw data into easily digestible formats, revealing trends and correlations that might otherwise be obscured. This section explores several common visualization techniques used in economic analysis.

Line Graph: Inflation and Unemployment

A line graph is ideal for showing the relationship between two variables over time. To illustrate the relationship between inflation and unemployment, we can create a graph with time (e.g., years) on the horizontal axis and inflation rate (as a percentage) on the left vertical axis. A second line, using the right vertical axis, would represent the unemployment rate (as a percentage). The lines would visually demonstrate whether inflation and unemployment move in the same direction (positive correlation) or opposite directions (negative correlation), potentially highlighting periods of stagflation (high inflation and high unemployment) or periods consistent with the Phillips Curve (inverse relationship). For example, a graph might show inflation rising while unemployment falls initially, then both increasing together, illustrating a complex, non-linear relationship.

Bar Chart: GDP Growth Across Sectors

A bar chart effectively compares the performance of different economic sectors. The horizontal axis would list the various sectors (e.g., agriculture, manufacturing, services, technology). The vertical axis would represent the GDP growth rate (as a percentage) for each sector during a specific period (e.g., a year or quarter). The length of each bar would correspond to the GDP growth rate in that sector, allowing for easy comparison of relative performance. For instance, a bar chart might show that the technology sector experienced significantly higher growth than the agriculture sector during a particular economic expansion.

Scatter Plot: Interest Rates and Investment

A scatter plot is useful for examining the correlation between two variables. In this case, we can plot interest rates (on the horizontal axis, as a percentage) against investment levels (on the vertical axis, perhaps as a total dollar amount or as a percentage of GDP). Each point on the graph represents a specific time period, showing the corresponding interest rate and investment level. The overall pattern of the points would suggest the strength and direction of the correlation. A negative correlation would indicate that higher interest rates are associated with lower investment levels, while a positive correlation would suggest the opposite. For example, a scatter plot might reveal a predominantly negative correlation, indicating that increases in interest rates tend to dampen investment, particularly in sectors sensitive to borrowing costs.

Impact of Economic Indicators on Businesses

Economic indicators provide crucial insights into the overall health and direction of the economy, offering businesses valuable information for strategic decision-making. Understanding and interpreting these indicators allows companies to anticipate market trends, adjust their operations proactively, and ultimately improve their chances of success. This section will explore how businesses leverage economic indicators for strategic planning and investment decisions.

Businesses use economic indicators to inform their strategic planning process in several key ways. By monitoring indicators like GDP growth, inflation rates, unemployment levels, and consumer confidence, businesses can gain a clearer understanding of the current economic climate and anticipate future trends. This information helps in setting realistic sales targets, managing inventory levels, and making informed decisions about resource allocation. For example, a company might reduce its marketing budget during a period of economic recession, focusing instead on cost-cutting measures. Conversely, during periods of strong economic growth, they might increase investment in expansion and new product development.

Strategic Planning and Economic Indicators

Economic indicators play a pivotal role in a company’s strategic planning. For instance, a rise in consumer confidence, reflected in increased consumer spending, might signal a favorable environment for businesses to launch new products or expand into new markets. Conversely, a sharp increase in inflation could prompt businesses to reassess their pricing strategies and explore cost-saving initiatives to maintain profitability. Analyzing leading indicators, such as manufacturing orders or building permits, can provide early warning signs of future economic activity, allowing businesses to adjust their plans accordingly. A company seeing a drop in leading indicators might choose to postpone major investments or focus on streamlining operations to weather a potential economic downturn.

Influence of Economic Indicators on Investment Decisions

Economic indicators significantly influence investment decisions. Businesses consider indicators such as interest rates, inflation, and stock market performance when deciding whether to invest in new projects, equipment, or expansion. Low interest rates, for example, can encourage businesses to borrow money for investments, while high inflation might lead to delaying or scaling back investment plans due to increased costs. The expectation of future economic growth, often signaled by leading indicators, can also significantly influence investment decisions. A positive outlook might lead to increased investment in research and development or the acquisition of other companies. Conversely, a pessimistic outlook based on lagging indicators, such as high unemployment rates, may lead to reduced investment and a more conservative approach.

Business Operational Adjustments Based on Economic Forecasts

Businesses regularly adjust their operations based on economic forecasts derived from economic indicators. For example, during periods of anticipated economic slowdown, businesses may implement cost-cutting measures, such as reducing workforce or delaying hiring. They might also focus on improving operational efficiency to maintain profitability in a less favorable economic environment. Conversely, during periods of strong economic growth, businesses may increase production, hire more employees, and expand their operations to meet rising demand. A company anticipating a surge in consumer spending based on positive economic forecasts might increase its inventory levels to avoid stockouts. Conversely, if forecasts predict a decrease in consumer spending, the company may reduce its inventory to minimize storage costs and potential losses from unsold goods.

Limitations of Economic Indicators

Economic indicators, while invaluable tools for understanding the state of an economy, are not without their limitations. Their accuracy and usefulness are contingent upon several factors, and relying solely on them for decision-making can be misleading. A comprehensive understanding of these limitations is crucial for informed interpretation and application.

While economic indicators provide a valuable snapshot of economic activity, several factors can compromise their accuracy and reliability. These limitations stem from both the methodology of data collection and the inherent complexities of economic systems.

Data Collection Biases and Inaccuracies

The accuracy of economic indicators is directly tied to the quality of the data collected. Data collection methods can introduce biases, leading to inaccurate or incomplete representations of the economy. For instance, the unemployment rate, a key indicator, relies on surveys and self-reporting, which may not capture the true extent of underemployment or discouraged workers. Similarly, GDP calculations can be affected by the methodologies used to estimate the value of informal or underground economic activities, which are often difficult to measure accurately. Revisions to previously reported data are common, highlighting the ongoing refinement and potential inaccuracies in the initial figures. For example, revisions to GDP growth figures are often made months or even years after the initial release, reflecting a more accurate picture after additional data becomes available.

Challenges in Interpretation Due to Unforeseen Events

Economic indicators are often developed based on historical patterns and relationships. However, unforeseen events, such as natural disasters, global pandemics, or unexpected geopolitical shifts, can significantly disrupt these patterns and render traditional interpretations unreliable. The COVID-19 pandemic, for example, dramatically altered economic activity worldwide, making it challenging to interpret indicators based on pre-pandemic trends. The rapid and unexpected nature of such events often means that indicators may lag behind the actual economic reality, leading to delayed or inaccurate assessments.

Limitations of Using Economic Indicators in Isolation

Relying on a single or a small set of economic indicators to make decisions is inherently risky. Economic phenomena are complex and multifaceted, influenced by a vast array of interconnected factors. A narrow focus on a limited number of indicators can lead to a skewed and incomplete understanding of the overall economic situation. For instance, focusing solely on GDP growth might overlook issues such as income inequality or environmental sustainability. A holistic approach that considers a broader range of indicators, along with qualitative assessments, is necessary for a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding. Furthermore, the context surrounding the indicators is critical; a high inflation rate, for instance, might be a positive sign in a period of low unemployment and strong economic growth, but a negative sign during a recession.

Closure

In conclusion, economic indicators are indispensable tools for analyzing and predicting economic performance. While limitations exist in data collection and interpretation, a thorough understanding of these metrics—including their classifications, calculations, and applications—is essential for navigating the dynamic landscape of the global economy. By mastering the art of interpreting economic data, individuals and organizations can make more informed decisions, mitigating risks and capitalizing on opportunities presented by evolving economic trends.

Question & Answer Hub

What is the difference between nominal and real GDP?

Nominal GDP is calculated using current market prices, while real GDP adjusts for inflation, providing a more accurate reflection of economic growth.

How is the Consumer Price Index (CPI) calculated?

The CPI tracks the average change in prices paid by urban consumers for a basket of consumer goods and services over time.

What are some limitations of using only leading indicators for forecasting?

Leading indicators can be inaccurate due to unforeseen events and may not always accurately predict future economic trends. They are most effective when used in conjunction with other indicators.

How do economic indicators impact the stock market?

Strong economic indicators often lead to increased investor confidence and higher stock prices, while weak indicators can trigger market declines.