Understanding economic indicators is crucial for navigating the complexities of the modern financial landscape. Whether you’re a seasoned investor, a budding entrepreneur, or simply a curious individual, grasping the nuances of leading, lagging, and coincident indicators empowers you to make informed decisions and anticipate future economic trends. This guide unravels the mysteries of these key indicators, offering a clear and accessible pathway to economic literacy.

From deciphering the intricacies of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) to predicting market shifts based on changes in manufacturing new orders, this guide provides a comprehensive framework for interpreting economic data. We’ll explore how these indicators interact, how they inform government policy, and ultimately, how they can impact your financial well-being. We will also examine the challenges in interpreting sometimes conflicting signals and offer best practices for navigating the wealth of information available.

Introduction to Economic Indicators

Understanding economic indicators is crucial for both individuals and businesses to make informed decisions. These indicators provide a snapshot of the economy’s current state and can help predict future trends. For individuals, this knowledge can inform savings, investment, and spending choices. Businesses rely on economic indicators to guide strategic planning, resource allocation, and investment decisions, ultimately impacting profitability and growth.

Economic indicators are quantifiable measures that reflect the performance and health of an economy. They are broadly classified into three categories: leading, lagging, and coincident indicators. These classifications describe the timing of the indicator’s relationship to the overall economic cycle.

Economic Indicator Classification

Leading indicators precede changes in the overall economy. They signal potential future trends, allowing for proactive adjustments. These indicators are often used to forecast future economic activity. Examples include the Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI), consumer confidence index, building permits, and the yield curve (the difference between long-term and short-term interest rates). A decline in the PMI, for example, might suggest a future slowdown in manufacturing activity.

Lagging indicators reflect past economic activity. They confirm trends that have already occurred and are often used to validate earlier predictions made using leading indicators. Examples include unemployment rate, inflation rate, and the average duration of unemployment. A rise in the unemployment rate often confirms a previous economic downturn.

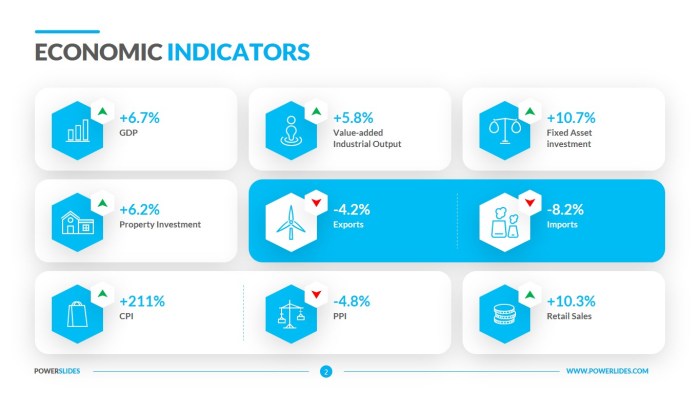

Coincident indicators move in tandem with the overall economy. They provide a current picture of economic conditions. Examples include GDP (Gross Domestic Product), industrial production, personal income, and retail sales. A surge in retail sales, for instance, indicates strong current consumer spending.

Interaction of Economic Indicators

Different economic indicators are interconnected and influence each other. For example, a rise in consumer confidence (a leading indicator) might lead to increased consumer spending (a coincident indicator). This increased spending, in turn, could stimulate job growth, eventually leading to a decrease in the unemployment rate (a lagging indicator). Conversely, rising interest rates (often a leading indicator reflecting monetary policy changes) can curb inflation (a lagging indicator) but might also slow down economic growth, potentially leading to higher unemployment. The intricate interplay between these indicators provides a holistic view of the economy’s dynamic nature. Analyzing multiple indicators simultaneously offers a more comprehensive understanding than relying on any single metric. For instance, a strong GDP growth accompanied by rising inflation and stagnant wages might suggest an economy overheating, while a weak GDP with low inflation and falling unemployment might signal a period of slow but stable growth.

Leading Economic Indicators

Leading economic indicators are valuable tools for economists and policymakers, offering insights into the future direction of the economy. They provide early warnings of potential economic expansions or contractions, allowing for proactive measures to mitigate risks or capitalize on opportunities. However, it’s crucial to understand both their strengths and weaknesses to interpret them effectively.

Leading indicators, by their nature, precede actual economic changes. This anticipatory characteristic makes them powerful forecasting tools. However, their predictive power isn’t absolute; they can be influenced by various factors, leading to inaccurate predictions at times. Furthermore, the lead time—the period between the indicator’s change and the actual economic shift—can vary, adding complexity to interpretation. Finally, leading indicators are not always perfectly correlated with the overall economy, meaning a change in one indicator doesn’t guarantee a corresponding change in the broader economic picture.

Characteristics and Limitations of Leading Indicators

Leading indicators possess several key characteristics. They are forward-looking, reflecting changes in economic activity before they are officially recorded. They are often volatile, fluctuating more readily than lagging indicators. This volatility can make them challenging to interpret. Their sensitivity to changes in consumer and business sentiment means they can react swiftly to economic shifts. However, this sensitivity can also amplify noise and make it difficult to distinguish genuine trends from temporary fluctuations. Limitations include their susceptibility to false signals, meaning a change in an indicator might not accurately predict the future. The indicators are often subject to revisions as more data becomes available. Furthermore, different leading indicators may send conflicting signals, adding to the interpretation challenge. For example, a rise in consumer confidence might be offset by a decline in manufacturing new orders, leading to uncertainty about the overall economic outlook.

Comparison of Leading Indicators

The following table compares three leading economic indicators: the Consumer Confidence Index, Building Permits, and Manufacturing New Orders.

| Indicator | Description | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer Confidence Index | Measures consumer optimism about the economy, based on surveys. | Provides insights into consumer spending intentions, a major driver of economic growth. Relatively quick to react to changes in economic sentiment. | Can be influenced by short-term factors like news events, leading to volatility. May not accurately reflect the spending behavior of all consumer segments. |

| Building Permits | Measures the number of permits issued for new residential and commercial construction. | Indicates future investment in construction and related industries. A strong predictor of future construction activity and related job creation. | Can be sensitive to changes in interest rates and lending conditions. The time lag between permit issuance and actual construction can be significant. |

| Manufacturing New Orders | Measures the value of new orders received by manufacturers. | Indicates future manufacturing output and employment. Provides insights into business investment and production plans. | Can be influenced by inventory levels and global demand. May not reflect the entire manufacturing sector equally, due to sector-specific variations. |

Predicting Future Economic Trends with Leading Indicators

Changes in leading indicators can offer valuable clues about the direction of the economy. For instance, a sustained increase in consumer confidence, coupled with a rise in building permits and manufacturing new orders, often suggests an impending economic expansion. Conversely, a decline in these indicators could signal a potential recession. The 2008 financial crisis, for example, was preceded by a significant decline in several leading indicators, including housing starts (related to building permits) and consumer confidence, offering early warnings, though not perfectly precise ones, of the impending downturn. It’s important to note that relying solely on one indicator is insufficient; a holistic approach, considering multiple indicators concurrently, provides a more robust and nuanced prediction. The interplay between different indicators and their combined signals paint a more complete picture of the economic landscape and its likely trajectory.

Lagging Economic Indicators

Lagging economic indicators, unlike their leading counterparts, don’t predict future economic activity; instead, they confirm past trends. They provide valuable insights into the overall health of the economy after a period of change, helping to understand the full impact of previous economic shifts. Their delayed nature, however, means they are less useful for short-term forecasting.

Three key examples of lagging indicators are the unemployment rate, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for inflation, and corporate profits. The unemployment rate reflects job losses or gains that have already occurred, providing a retrospective view of the labor market’s performance. Similarly, CPI data reflects past price changes, giving a delayed picture of inflation. Corporate profits, finally, represent the financial outcomes of past business activities, offering a delayed snapshot of the economy’s overall profitability.

Reasons for Lagging Indicators’ Delayed Nature

These indicators lag because they represent the culmination of various economic processes that unfold over time. The unemployment rate, for instance, reflects the delayed effect of economic slowdown or expansion on hiring and firing decisions. Businesses don’t immediately lay off workers when economic conditions worsen; there’s a delay as companies assess the situation and implement cost-cutting measures. Likewise, inflation, as measured by CPI, is a gradual process; price changes don’t occur instantaneously but rather reflect a complex interplay of supply and demand over a period. Corporate profits similarly reflect the cumulative effect of sales, production, and expenses over a reporting period, and these take time to materialize and be fully reported.

Comparison of Leading and Lagging Indicators for Economic Forecasting

Leading indicators offer forward-looking insights, providing clues about potential future economic trends. They are useful for anticipating changes, allowing businesses and policymakers to prepare. Lagging indicators, on the other hand, confirm past trends and provide a more complete picture of the economy’s state after the fact. They are less useful for short-term forecasting but invaluable for validating predictions made using leading indicators and for providing a more complete understanding of the economic cycle’s progression. The combination of both leading and lagging indicators provides a more comprehensive and nuanced view of the economy’s current state and likely future direction. For example, a rise in consumer confidence (leading indicator) might be later confirmed by an increase in retail sales (lagging indicator).

Implications of Significant Changes in a Lagging Indicator

A significant change in a lagging indicator signifies a substantial shift in the economy’s state. For instance, a sustained rise in the unemployment rate indicates a prolonged period of economic weakness, while a significant drop suggests a robust recovery. A sharp increase in the CPI confirms a period of high inflation, impacting consumer purchasing power and potentially necessitating policy intervention. Similarly, a substantial decrease in corporate profits signals a weakening in business activity and potential future economic challenges. These significant changes provide policymakers with critical information for adjusting economic policies, informing business strategies, and providing a clearer understanding of the economy’s overall health and future direction. For example, a sharp rise in the unemployment rate following a recession could trigger government intervention to stimulate job creation through various fiscal and monetary policies.

Coincident Economic Indicators

Coincident economic indicators provide a snapshot of the current state of the economy. Unlike leading indicators that predict future trends, or lagging indicators that confirm past performance, coincident indicators offer real-time insights into the economy’s performance at a specific point in time. They are valuable tools for economists and policymakers seeking to understand the immediate economic climate and make informed decisions. Analyzing these indicators in conjunction with leading and lagging indicators provides a more comprehensive view of the economic cycle.

Several key coincident indicators offer valuable perspectives on the economy’s current health. These indicators, while not perfect, provide a relatively timely and accurate picture of economic activity.

Personal Income and Spending

Personal income and consumer spending represent a significant portion of overall economic activity. Personal income reflects the total earnings of households, including wages, salaries, investment income, and government transfers. Consumer spending, on the other hand, tracks how much households spend on goods and services. A rise in personal income usually leads to increased consumer spending, boosting economic growth. Conversely, a decline in personal income often results in reduced spending, potentially signaling an economic slowdown.

- Strengths: Directly reflects the purchasing power and consumption habits of a large segment of the population, providing a clear picture of current economic activity.

- Weaknesses: Can be influenced by factors outside of general economic health, such as changes in government transfer payments or shifts in consumer confidence unrelated to overall economic performance.

Industrial Production

Industrial production measures the output of factories, mines, and utilities. It’s a key indicator of the manufacturing sector’s health and its contribution to overall economic growth. A surge in industrial production often signals robust economic expansion, while a decline can indicate weakening manufacturing activity and potential economic contraction. This indicator is particularly sensitive to changes in business investment and consumer demand for manufactured goods.

- Strengths: Offers a direct measure of the output of a significant portion of the economy, providing a clear signal of manufacturing sector performance.

- Weaknesses: Can be heavily influenced by short-term fluctuations in production, such as seasonal changes or temporary disruptions in supply chains. It might not fully capture the service sector’s contribution to the economy.

Employment

Employment data, specifically non-farm payroll employment, is a critical coincident indicator. This data, collected by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, reflects the number of people employed in the non-agricultural sector of the economy. A rising employment level generally signifies a healthy economy with strong demand for labor. Conversely, a decline in employment often indicates a weakening economy and potential job losses. Changes in the unemployment rate, a closely related indicator, also offer insights into the labor market’s condition.

- Strengths: Provides a direct measure of the labor market’s health, a key component of overall economic activity and a strong indicator of consumer confidence and spending.

- Weaknesses: Can lag behind other indicators in reflecting economic changes, as employers may delay hiring or firing decisions. The data can also be affected by temporary factors, such as seasonal adjustments or changes in workforce participation rates.

By analyzing these coincident indicators together, economists can gain a comprehensive understanding of the current state of the economy. For example, a simultaneous increase in personal income and spending, strong industrial production, and rising employment would strongly suggest a robust and expanding economy. Conversely, a decline across these indicators would paint a picture of economic contraction. It’s crucial to remember that no single indicator provides a complete picture, and a holistic approach considering all available data is essential for accurate economic assessment.

Interpreting Economic Data

Understanding economic indicators is only half the battle; interpreting the data they provide is crucial for making informed decisions. This section explores common statistical methods used to analyze economic data and offers strategies for navigating potentially conflicting signals.

Analyzing economic data often involves comparing figures over time to understand trends and patterns. This involves using several statistical methods to reveal meaningful insights. Simple calculations like growth rates and year-over-year comparisons are frequently employed, while more complex techniques, such as regression analysis and econometric modeling, are used for deeper dives.

Growth Rates

Growth rates express the percentage change in a variable over a specific period. For instance, a 2% growth rate in GDP indicates a 2% increase in the total value of goods and services produced within a country’s borders compared to the previous period (usually a quarter or a year). Calculating growth rates involves subtracting the previous period’s value from the current period’s value, dividing the result by the previous period’s value, and then multiplying by 100 to express the result as a percentage. The formula is:

Growth Rate = [(Current Value – Previous Value) / Previous Value] * 100

This simple calculation provides a clear picture of economic expansion or contraction. For example, a consistently positive growth rate in GDP usually suggests a healthy economy, while a negative growth rate often indicates a recession.

Year-Over-Year Comparisons

Year-over-year comparisons provide a clearer picture of economic trends by comparing the current period’s data with the same period from the previous year. This helps to smooth out seasonal fluctuations and short-term variations, revealing underlying trends more accurately. For example, comparing retail sales in December 2024 to December 2023 accounts for the usual holiday shopping surge, giving a better understanding of the underlying sales trend. This method is particularly useful for identifying longer-term patterns and assessing the overall health of the economy.

Interpreting Conflicting Signals

Economic indicators often send mixed signals. Consider a hypothetical scenario: Unemployment is low (a positive sign), indicating a strong labor market. However, consumer confidence is down (a negative sign), suggesting potential future economic slowdown due to reduced consumer spending. Simultaneously, inflation is rising (a negative sign), potentially dampening consumer spending further and increasing the likelihood of a central bank interest rate hike. In this case, a thorough analysis is required, considering the relative importance and potential impact of each indicator, before drawing any conclusions. The low unemployment rate might be offset by the negative consumer confidence and rising inflation, suggesting a potential future economic slowdown despite the current strong labor market. Further investigation into the causes of declining consumer confidence and the rate of inflation would be crucial for a complete understanding.

Interpreting Graphs and Charts

Graphs and charts are essential tools for visualizing economic data. Understanding the type of chart used is crucial. Line charts effectively display trends over time, while bar charts compare data across different categories. Pie charts illustrate proportions, and scatter plots show the relationship between two variables. Pay close attention to the axes, labels, and scales. A manipulated scale can distort the data, creating a misleading impression. Always consider the source of the data and its potential biases. Look for clear explanations of the data presented and be wary of charts lacking clear labels or context. Understanding the context and methodology behind the data visualization is crucial for accurate interpretation.

Economic Indicators and Policy Decisions

Economic indicators serve as vital guides for governments in formulating and implementing both monetary and fiscal policies. By analyzing trends in various indicators, policymakers gain insights into the current state of the economy and can make informed decisions to promote sustainable growth, control inflation, and manage unemployment. The effectiveness of these policies, however, is heavily reliant on the accuracy and timely availability of the data, as well as the understanding of the complex interplay between different economic factors.

Policymakers utilize economic indicators to assess the overall health of the economy and to anticipate future trends. This information is crucial in determining the appropriate policy response. For instance, rising inflation, indicated by a consistently increasing Consumer Price Index (CPI), might prompt the central bank to implement contractionary monetary policy, such as raising interest rates to cool down the economy. Conversely, high unemployment rates, as revealed by the unemployment rate, could lead to expansionary fiscal policies, such as increased government spending or tax cuts, to stimulate economic activity and job creation.

Monetary Policy Responses to Economic Indicator Trends

Changes in key economic indicators directly influence central bank decisions regarding monetary policy. For example, a sustained increase in inflation, as measured by the CPI or Producer Price Index (PPI), often triggers an increase in interest rates. This makes borrowing more expensive, reducing consumer spending and investment, thereby curbing inflationary pressures. Conversely, during periods of economic slowdown, indicated by falling GDP growth and rising unemployment, central banks may lower interest rates to encourage borrowing and stimulate economic activity. The Federal Reserve’s actions in response to the 2008 financial crisis, where interest rates were slashed to near-zero, serve as a prime example of this approach. The effectiveness of such policies, however, depends on numerous factors, including the responsiveness of the economy to interest rate changes and the presence of other economic shocks.

Fiscal Policy Responses to Economic Indicator Trends

Fiscal policy, encompassing government spending and taxation, is also significantly influenced by economic indicators. A significant decline in GDP growth, coupled with high unemployment, may prompt governments to increase spending on infrastructure projects or implement tax cuts to boost aggregate demand. This expansionary fiscal policy aims to stimulate economic activity and create jobs. Conversely, during periods of rapid economic growth and rising inflation, governments might choose to reduce spending or increase taxes to curb inflation and prevent the economy from overheating. The implementation of austerity measures in several European countries following the 2008 financial crisis illustrates a contractionary fiscal policy response to high debt levels and slow growth.

Challenges in Using Economic Indicators for Policymaking

Despite their importance, economic indicators present several challenges for policymakers. The accuracy and timeliness of data are crucial, yet delays in data collection and potential revisions can hinder effective policymaking. Furthermore, the complex interplay of various economic factors makes it difficult to isolate the impact of a specific policy response. For instance, a rise in inflation might be due to a combination of factors, including supply chain disruptions, increased demand, and monetary policy decisions, making it challenging to determine the most appropriate policy intervention. Moreover, economic indicators often lag behind actual economic changes, meaning that policymakers might be reacting to past events rather than current realities. Finally, the forecasting power of economic indicators is not perfect; unexpected events, such as geopolitical crises or technological disruptions, can significantly alter economic trends, rendering forecasts inaccurate and policy responses less effective.

Illustrative Example: Inflation

Inflation, a sustained increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy over a period of time, is a crucial economic indicator. Understanding its components, calculation, and impact is vital for policymakers and citizens alike. This section will delve into the specifics of inflation using the Consumer Price Index (CPI) as a primary example.

Consumer Price Index (CPI) Components and Calculation

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) measures the average change in prices paid by urban consumers for a basket of consumer goods and services. This “basket” is carefully constructed to represent the typical spending patterns of a household. It includes a wide range of items, categorized into various groups such as food, housing, transportation, medical care, and recreation. The weights assigned to each category reflect their relative importance in the average consumer’s budget.

The CPI is calculated by comparing the price of this basket of goods and services in a given period to the price of the same basket in a base period. The percentage change represents the rate of inflation. For example, if the CPI in year X is 100 and in year Y is 110, the inflation rate is 10%. The calculation involves intricate weighting schemes and adjustments to account for quality changes in goods and services over time, ensuring accuracy in reflecting actual price changes. This complex process is undertaken by government statistical agencies, such as the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) in the United States.

Inflation’s Impact on Different Population Segments

Inflation’s effects are not uniform across the population. Low-income households are disproportionately affected because a larger portion of their income is spent on essential goods and services, like food and housing, which are often more susceptible to price increases. Fixed-income earners, such as retirees relying on pensions, also face significant challenges as their purchasing power diminishes with rising prices. Conversely, high-income earners, who may have assets that appreciate with inflation (like real estate), might experience a less severe impact. Furthermore, individuals with significant debt may benefit from inflation as the real value of their debt decreases. Businesses also experience varying impacts, depending on their ability to pass on increased costs to consumers.

Inflation and Unemployment Relationship

A visual representation of the relationship between inflation and unemployment could be depicted as a curve, often referred to as the Phillips Curve. This curve generally shows an inverse relationship: low unemployment is often associated with high inflation, and high unemployment is often associated with low inflation. However, this relationship is not always consistent and can shift over time due to various economic factors. For instance, during periods of stagflation (simultaneous high inflation and high unemployment), the curve shifts, illustrating the complexities of this interaction. The curve would be presented as a downward-sloping line, demonstrating the general inverse relationship but with a caveat of potential shifts and exceptions.

Resources for Further Learning

Understanding economic indicators requires ongoing learning and engagement with diverse data sources. This section provides resources to enhance your knowledge and skills in interpreting economic data effectively. It emphasizes the importance of critical evaluation and navigating complex data websites.

Reliable sources for economic data and analysis are crucial for informed decision-making. Different organizations offer unique perspectives and methodologies, so understanding their strengths and limitations is essential. Furthermore, developing effective strategies for navigating the often complex layouts of economic data websites will significantly improve your efficiency and accuracy.

Reputable Sources of Economic Data and Analysis

Several organizations provide high-quality, regularly updated economic data and analysis. Accessing these resources offers a broad perspective on economic trends and allows for comparisons across different datasets and methodologies.

- International Monetary Fund (IMF): The IMF offers global economic forecasts, data on individual countries, and analysis of various economic issues. Their website is a comprehensive resource for international economic trends.

- World Bank: The World Bank provides data and reports on global development, including economic growth, poverty, and various social indicators. Their data is often used to track progress towards sustainable development goals.

- Federal Reserve (US): The Federal Reserve publishes a wide range of economic data for the United States, including monetary policy decisions, economic forecasts, and reports on financial stability.

- Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA, US): The BEA is the primary source for US national economic accounts, including GDP, personal income, and business investment data.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS, US): The BLS provides detailed data on employment, unemployment, wages, and prices in the US. Their data is frequently used to track the labor market’s health.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD): The OECD compiles and analyzes economic data for its member countries, providing insights into economic performance and policy implications.

Critically Evaluating Economic Information

It’s crucial to approach economic data with a critical eye. Understanding the source’s potential biases, methodologies, and data limitations is essential for accurate interpretation. Different sources may use different methodologies, leading to variations in reported figures. Therefore, cross-referencing data across multiple sources is recommended.

- Source Credibility: Assess the reputation and expertise of the organization providing the data. Look for transparency in methodology and data collection processes.

- Data Methodology: Understand how the data was collected, processed, and analyzed. Different methodologies can lead to varying results.

- Potential Biases: Consider whether the source might have any inherent biases that could influence the data or its interpretation. For example, a report funded by a specific industry might present data in a way that favors that industry.

- Data Revisions: Be aware that economic data is often revised as more information becomes available. Compare data across different revisions to understand the potential impact of revisions on conclusions.

- Contextual Understanding: Consider the broader economic context when interpreting data. Isolated data points can be misleading without understanding the surrounding economic conditions.

Navigating Economic Data Websites

Many economic data websites can be complex to navigate. A structured approach can greatly improve efficiency and accuracy in finding the needed information. Familiarizing yourself with the website’s structure and search functionalities is crucial.

- Understand the Website Structure: Most websites have a clear organizational structure. Look for sections dedicated to specific data categories (e.g., GDP, inflation, employment).

- Utilize Search Functions: Most websites have powerful search functions. Use specific s to narrow your search and locate the desired data quickly.

- Data Downloads: Learn how to download data in formats suitable for analysis (e.g., CSV, Excel). Many websites offer tools to customize data downloads.

- Data Definitions and Methodologies: Always check the definitions and methodologies used to collect and calculate the data. This ensures you are interpreting the data correctly.

- Data Visualization Tools: Many websites provide tools to visualize data in charts and graphs. These tools can help you understand trends and patterns more easily.

Concluding Remarks

By mastering the art of interpreting economic indicators, you gain a powerful tool for understanding the economic pulse of the world. This guide has provided a foundation for understanding the different types of indicators, their limitations, and their applications in forecasting and policymaking. Remember that continuous learning and critical evaluation of data sources are key to becoming a truly informed economic observer. Armed with this knowledge, you can confidently navigate the complexities of the global economy and make well-informed decisions for your future.

FAQ Compilation

What is the difference between nominal and real GDP?

Nominal GDP is the value of goods and services produced in a year using current prices, while real GDP adjusts for inflation, providing a more accurate measure of economic growth.

How frequently are economic indicators released?

The frequency varies depending on the indicator. Some, like the CPI, are released monthly, while others, like GDP, are released quarterly or annually.

Are economic indicators always accurate predictors of the future?

No, economic indicators are subject to revisions and can be influenced by unforeseen events. They provide valuable insights but should not be considered infallible predictions.

Where can I find reliable data on economic indicators?

Reputable sources include government agencies (like the Bureau of Economic Analysis in the US), central banks, and international organizations (like the IMF and World Bank).