Economic Indicators Explanation Guide: Brace yourselves, dear readers, for a journey into the often-bewildering, yet surprisingly hilarious, world of economic indicators! We’ll unravel the mysteries of leading, lagging, and coincident indicators, revealing their secrets (and their occasional comedic failures) in a way that’s both informative and, dare we say, entertaining. Forget dry economic textbooks; get ready for a rollercoaster ride through the data!

This guide will equip you with the knowledge to decipher the cryptic pronouncements of economists and impress your friends (or at least avoid embarrassing yourself at cocktail parties) with your newfound understanding of economic trends. We’ll explore how these indicators predict the future (sometimes accurately, sometimes hilariously not), help businesses make smart (or disastrously funny) decisions, and even shed light on how they impact your personal finances. So buckle up, and let’s get started!

Introduction to Economic Indicators

Economic indicators, my friends, are the crystal ball of the economy – not a perfect one, mind you, more like a slightly cloudy crystal ball that occasionally throws a wrench into the works, but a crystal ball nonetheless! They’re essentially the vital signs of a nation’s economic health, providing a snapshot of its current state and offering clues about its future trajectory. Think of them as the economy’s very own, slightly eccentric, medical checkup.

Understanding economic indicators is crucial, whether you’re a seasoned CEO, a small business owner trying to navigate the choppy waters of entrepreneurship, or simply someone who wants to make better financial decisions. For businesses, indicators inform strategic planning, investment choices, and even hiring decisions. For individuals, they can help you time major purchases, adjust your investment portfolio, and generally understand the economic landscape you’re navigating. Ignoring them is like trying to drive a car blindfolded – you might get lucky, but the odds are stacked against you.

Types of Economic Indicators

Economic indicators are broadly categorized into three types: leading, lagging, and coincident. Leading indicators are, as the name suggests, early warning systems, predicting future economic activity. Think of them as the canary in the coal mine, though hopefully, a slightly less dramatic canary. Lagging indicators, on the other hand, confirm past economic trends – they’re the wise old owl, reflecting on what’s already happened. Finally, coincident indicators move in tandem with the overall economy, offering a real-time view of its current state. They’re the ever-present, slightly gossipy neighbor, always in the know.

Examples of Economic Indicators

Let’s delve into some specific examples. It’s important to remember that no single indicator tells the whole story; they’re most useful when considered together, like a well-orchestrated economic symphony.

| Indicator Name | Category | Description | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer Confidence Index | Leading | Measures consumer optimism regarding the economy. A high index suggests robust spending, while a low index signals potential economic slowdown. | Conference Board |

| Unemployment Rate | Lagging | Percentage of the labor force that is unemployed and actively seeking employment. A high rate often indicates a weak economy, but it can lag behind other indicators. | Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) |

| Gross Domestic Product (GDP) | Coincident | The total value of goods and services produced within a country’s borders in a specific period. A strong GDP growth usually indicates a healthy economy. | Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) |

| Housing Starts | Leading | The number of new residential construction projects that have begun. A rise often precedes economic expansion, while a fall can signal a contraction. | Census Bureau |

| Inflation Rate (CPI) | Lagging | Measures the average change in prices paid by urban consumers for a basket of consumer goods and services. High inflation can erode purchasing power. | Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) |

| Industrial Production | Coincident | Measures the output of factories, mines, and utilities. It provides insights into the manufacturing sector’s health. | Federal Reserve |

Leading Economic Indicators

Predicting the future is a tricky business, even for economists armed with spreadsheets and fancy coffee. However, leading economic indicators offer a glimpse into the crystal ball (though it’s a slightly cloudy one, admittedly). These indicators are economic variables that tend to change *before* the overall economy shifts, providing a heads-up about potential booms or busts. Think of them as the economy’s early warning system, albeit one that occasionally yells “wolf!” when it’s just a particularly fluffy sheep.

Leading indicators don’t offer foolproof predictions, but they provide valuable insights for businesses, policymakers, and anyone interested in the economic rollercoaster. Their predictive power comes from the fact that they reflect changes in consumer and business sentiment before these changes fully manifest in broader economic data. The accuracy of these predictions, however, depends heavily on the indicator used and the economic context.

Characteristics of Leading Indicators and Their Predictive Power

Leading indicators are characterized by their tendency to change direction *before* the overall economy. This anticipatory nature is what makes them so valuable for forecasting. Their predictive power, however, is not perfect; it’s more of a probabilistic assessment than a guaranteed outcome. For example, a sharp rise in consumer confidence might foreshadow increased spending, but other factors could intervene and dampen that effect. The strength of their predictive power can also vary depending on the specific indicator and the economic climate. A leading indicator might be highly predictive during periods of rapid economic change, but less so during times of stability.

Key Leading Indicators

Several key leading indicators help economists paint a picture of the future. Let’s examine five prominent examples:

- Consumer Confidence: This measures consumers’ optimism about the economy, influencing spending habits. A surge in confidence often precedes increased consumer spending, boosting economic growth. Conversely, plummeting confidence can signal a downturn. Think of it as the collective gut feeling of the nation’s shoppers – a rather powerful force.

- Building Permits: The number of building permits issued is a strong predictor of future construction activity. A rise in permits signals increased investment in housing and infrastructure, contributing to economic expansion. A decline suggests a potential slowdown in the construction sector and related industries.

- Manufacturing New Orders: This indicator reflects the demand for manufactured goods. A significant increase in new orders indicates robust future production and economic activity, while a decrease often precedes a manufacturing slowdown.

- Stock Market Indices: While not a direct measure of economic activity, stock market performance often anticipates economic trends. A rising stock market can signal investor confidence and future economic growth, while a declining market can be a harbinger of trouble. However, it’s crucial to remember that the stock market can be volatile and influenced by factors beyond the real economy.

- Average Weekly Hours Worked in Manufacturing: This metric reflects the level of employment and production in the manufacturing sector. An increase suggests businesses are anticipating higher demand and are thus increasing their workforce, often preceding an overall economic upturn.

Comparison of Leading Indicators

Different leading indicators have varying strengths and weaknesses. Consumer confidence, for example, is readily available and easily understood, but it can be influenced by short-term events and may not always accurately reflect actual spending behavior. Building permits, on the other hand, provide a more concrete measure of investment, but they are less timely than consumer confidence data. Each indicator offers a unique perspective, and a comprehensive analysis typically involves considering several indicators simultaneously.

Limitations of Leading Indicators

It’s crucial to acknowledge that leading indicators are not perfect predictors. Using them for forecasting involves several limitations:

- False Signals: Leading indicators can sometimes generate false signals, leading to inaccurate forecasts. A temporary spike in one indicator might not reflect a sustained economic trend.

- Lagging Effects: The time lag between the change in a leading indicator and the subsequent change in the overall economy can vary, making precise forecasting challenging.

- External Shocks: Unexpected events, such as natural disasters or geopolitical crises, can significantly impact the economy and render leading indicator forecasts unreliable.

- Data Revisions: Economic data is often revised, which can affect the accuracy of forecasts based on leading indicators.

- Interdependence of Indicators: The relationship between leading indicators and the overall economy can change over time, making it essential to continuously evaluate their predictive power.

Lagging Economic Indicators

Lagging economic indicators, unlike their more proactive leading brethren, are the economic equivalent of that friend who always arrives fashionably late – but with a very important piece of information. They don’t predict the future; they confirm what’s already happened. Think of them as the wise old owl, perched on a branch, calmly observing the aftermath and offering a measured assessment. Let’s delve into the fascinating world of these retrospective economic soothsayers.

These indicators are valuable because they provide a retrospective confirmation of economic trends identified by leading indicators. While they don’t help you predict the future, they provide a crucial reality check on the accuracy of previous predictions and analyses. Without lagging indicators, we’d be left with a lot of “maybe’s” and “perhaps’s” instead of concrete evidence.

Prominent Lagging Indicators and Their Time Lags

Three prominent lagging indicators provide a solid picture of the economy’s past performance. Understanding their inherent delay is key to interpreting their message correctly. The delay isn’t a flaw; it’s a feature, providing a more complete and less volatile view of the economic landscape.

| Indicator Name | Definition | Time Lag |

|---|---|---|

| Unemployment Rate | The percentage of the labor force actively seeking employment but unable to find it. | Several months. Businesses typically don’t immediately lay off workers when economic downturns begin, and hiring freezes often precede significant job losses. Similarly, recovery in employment often lags behind economic growth. |

| Average Prime Rate | The average interest rate that commercial banks charge their most creditworthy customers. | Several months to a year. Central banks typically adjust interest rates in response to changes in inflation and economic activity, but the effects of these adjustments take time to ripple through the economy and affect borrowing costs. |

| Consumer Price Index (CPI) | A measure of the average change in prices paid by urban consumers for a basket of consumer goods and services. | Several months. Inflation is a lagging indicator because changes in prices often reflect past changes in production costs, demand, and other economic factors. The CPI data is collected and compiled over time, resulting in a delay in its release. |

The Role of Lagging Indicators in Confirming Economic Trends

Lagging indicators play a crucial role in verifying the accuracy of economic forecasts and analyses based on leading indicators. They offer a crucial reality check, allowing economists to assess whether earlier predictions accurately reflected the subsequent economic reality. For instance, a sustained increase in the unemployment rate might confirm a recession predicted by leading indicators several months prior. This confirmation helps refine future forecasting models and improve the accuracy of economic projections.

Examples of Lagging Indicators in Economic Analysis

Imagine an economist predicting a recession based on a decline in leading indicators like consumer confidence and manufacturing orders. Months later, the unemployment rate starts to climb, confirming the recession. This confirmation provides policymakers with valuable data to design appropriate responses, such as fiscal stimulus or monetary policy adjustments. Similarly, a rise in the CPI, following a period of strong economic growth indicated by leading indicators, might suggest inflationary pressures are building, prompting central banks to consider raising interest rates to cool down the economy. The use of lagging indicators allows for a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the economic cycle.

Coincident Economic Indicators: Economic Indicators Explanation Guide

Coincident indicators, unlike their leading and lagging brethren, are the economic equivalent of that perfectly ripe avocado – they tell you exactly what’s happening *right now*. They’re not predicting the future or reflecting on the past; they’re a snapshot of the current economic climate. Think of them as the real-time pulse of the economy, providing a crucial understanding of the present state of affairs. This understanding is vital for policymakers, businesses, and anyone trying to navigate the often-turbulent waters of the economic landscape.

Coincident indicators are closely tied to the current state of the economy, rising and falling in tandem with overall economic activity. They offer a valuable, immediate picture of the economy’s health, allowing for a more informed assessment than solely relying on predictions or historical data. The speed at which these indicators are released is crucial, offering near-real-time insights into economic trends.

Key Coincident Economic Indicators

Several key indicators provide a comprehensive view of the current economic situation. These indicators are carefully chosen for their strong correlation with overall economic activity and their timely availability. Analyzing these indicators together paints a much richer and more accurate picture than examining any single metric in isolation.

- Personal Income: This measures the total income received by households, including wages, salaries, investment income, and government transfers. A rise in personal income usually signals increased consumer spending and overall economic growth. Conversely, a decline suggests weakening consumer demand and potential economic slowdown. For example, a significant increase in personal income during a period of low inflation might indicate strong economic expansion and robust consumer confidence.

- Industrial Production: This measures the output of factories, mines, and utilities. It’s a key indicator of manufacturing activity and overall industrial strength. A surge in industrial production often points towards a healthy economy, while a drop might signal a manufacturing downturn and broader economic weakness. Imagine a sharp increase in industrial production coupled with high consumer spending; that’s a strong indication of a booming economy.

- Manufacturing and Trade Sales: This indicator reflects the sales of manufactured goods and other traded products. Strong sales figures generally signify healthy demand and robust economic activity. Conversely, weak sales often precede economic downturns. A persistent decline in manufacturing and trade sales, for example, could be a warning sign of a recession, especially if accompanied by falling industrial production and employment figures.

- Employment: Specifically, the employment situation summary, encompassing the unemployment rate and nonfarm payroll employment, is a crucial coincident indicator. A low unemployment rate usually indicates a healthy economy with strong labor demand, while a rising unemployment rate is often a signal of economic trouble. For instance, a significant decrease in unemployment coupled with increased wages often suggests a strong and growing economy.

Assessment of the Current Economic Situation Using Coincident Indicators, Economic Indicators Explanation Guide

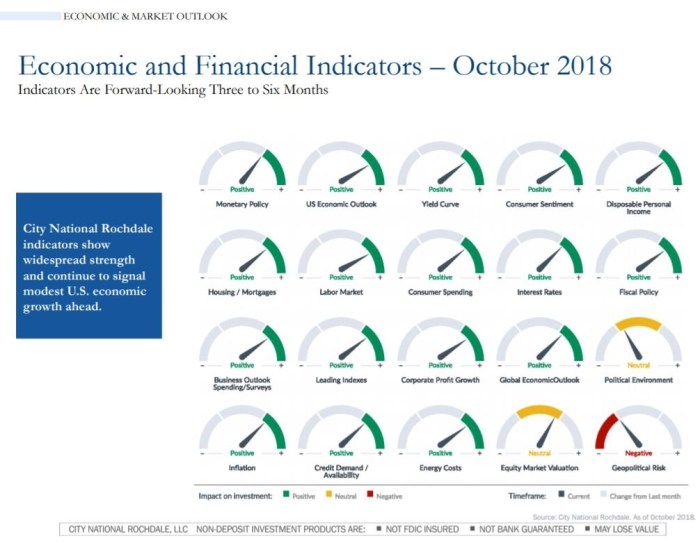

Economists and analysts use coincident indicators to gauge the current economic climate and to confirm or refute what leading indicators have suggested. By comparing the trends in these indicators, they can assess the overall health of the economy and identify potential turning points. For example, if personal income, industrial production, and employment are all rising, it strongly suggests a period of economic expansion. Conversely, a simultaneous decline in these indicators would signal an economic contraction. The power of coincident indicators lies in their ability to provide a holistic view, revealing the intricate interplay of various economic forces at work.

Compilation and Release of Coincident Indicators

These indicators are compiled from various sources, including government agencies (like the Bureau of Economic Analysis and the Bureau of Labor Statistics in the US), industry associations, and private sector surveys. Data is collected, processed, and verified rigorously before being released to the public. The frequency of release varies depending on the specific indicator; some are released monthly, while others are released quarterly. The timely and reliable release of this data is crucial for informed decision-making by businesses, investors, and policymakers. The consistency and accuracy of these releases are paramount to their usefulness as reliable indicators of the economic state.

Interpreting Economic Data

So, you’ve wrestled with leading, lagging, and coincident indicators – congratulations! You’re now fluent in the cryptic language of economic forecasting (almost). But numbers, like mischievous gremlins, can be misleading. This section unveils the secrets to deciphering economic data and avoiding the pitfalls that even seasoned economists sometimes stumble into. We’ll arm you with the tools to interpret the data, not just read it.

Common Methods of Analyzing Economic Data

Analyzing economic data isn’t just about staring at numbers; it’s about understanding the *story* they tell. Two fundamental methods help us unravel this narrative: year-over-year growth and percentage change. Year-over-year growth compares the current period’s data to the same period in the previous year, smoothing out short-term fluctuations. Percentage change, on the other hand, expresses the change in a variable as a percentage of its previous value, highlighting the rate of growth or decline. For example, if GDP increased from $20 trillion to $22 trillion, the year-over-year growth would be 10% ( ($22 trillion – $20 trillion) / $20 trillion * 100%). However, if GDP grew from $20 trillion to $21 trillion in the next year, then the year-over-year growth would only be 5%. The percentage change from one year to the next is also a useful tool to interpret trends and volatility in data.

The Importance of Seasonal Adjustments

Imagine trying to understand the health of a business by looking only at its December sales. The holiday rush would inflate the numbers, creating a misleading picture. Seasonal adjustments are like accounting for that holiday rush. They remove the predictable seasonal fluctuations from the data, allowing us to focus on the underlying trends. For instance, ice cream sales naturally spike in summer. Seasonal adjustment removes this predictable summer surge, revealing the true underlying trend in ice cream consumption. Without seasonal adjustment, we might mistakenly conclude that ice cream sales are booming every summer, while the reality might be a slow but steady growth.

Potential Biases and Limitations in Interpreting Economic Data

Economic data, much like a politician’s promises, can be spun to support almost any narrative. Biases can creep in through data collection methods, sampling errors, or even the way the data is presented. For instance, a survey might underrepresent certain demographics, leading to skewed results. Similarly, the way data is presented can heavily influence interpretation. A graph can be manipulated to exaggerate or downplay changes. Always look for the source of the data and its methodology before drawing conclusions. Furthermore, remember that economic data is a snapshot in time. It’s a reflection of past events, not a crystal ball predicting the future. Extrapolating trends too far into the future can be dangerous.

Interpreting a Simple Economic Indicator Graph

Let’s imagine a simple line graph showing unemployment rates over five years. To interpret it effectively, follow these steps:

- Identify the trend: Is the unemployment rate generally increasing, decreasing, or staying relatively flat?

- Look for significant changes: Are there any sharp increases or decreases that deviate from the overall trend? These might indicate specific economic events.

- Consider the context: What major economic events occurred during the period shown? Recessions, policy changes, or global events can influence unemployment.

- Compare to other indicators: Does the unemployment rate align with other economic indicators, like GDP growth or consumer spending? Discrepancies might suggest a more complex economic picture.

- Consider seasonal adjustments: Is the data seasonally adjusted? If not, be cautious of interpreting short-term fluctuations.

For example, if the graph shows a steady increase in unemployment alongside a decrease in GDP growth, it strongly suggests an economic slowdown. Conversely, a decrease in unemployment paired with strong GDP growth likely indicates a healthy economy. Remember, context is king!

Macroeconomic Indicators and Their Interrelationships

The economy, my friends, is a complex beast. It’s not just a collection of individual transactions; it’s a swirling vortex of interconnected variables, each influencing the others in a never-ending economic tango. Understanding these relationships is key to navigating the sometimes-chaotic world of macroeconomic analysis. Think of it as a giant, slightly wobbly Jenga tower – one misplaced indicator, and the whole thing could come tumbling down (or, you know, experience a recession).

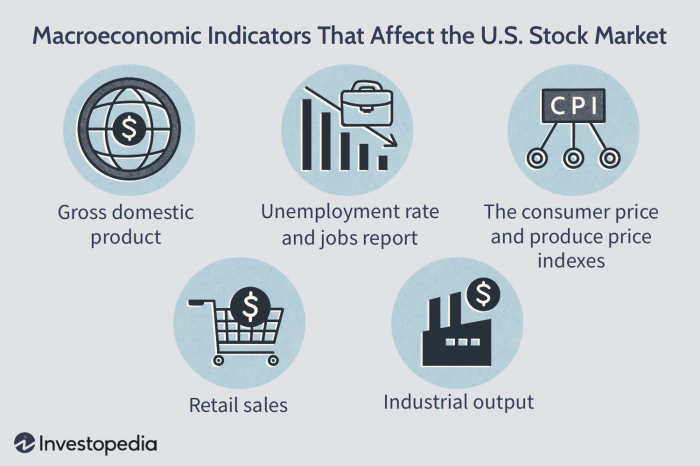

Three key macroeconomic indicators – GDP, inflation, and unemployment – form the unholy trinity of economic analysis. They are inextricably linked, each reacting to and influencing the others in a delicate (and often frustrating) dance. Changes in one often trigger a ripple effect throughout the entire economic ecosystem, impacting everything from consumer spending to government policy.

GDP, Inflation, and Unemployment: A Triangular Relationship

The relationship between GDP, inflation, and unemployment is often depicted using the Phillips Curve, although the relationship isn’t always perfectly linear in the real world. A simplified explanation would be this: High GDP growth (a booming economy) often leads to increased demand for labor, pushing down unemployment. However, this increased demand can also drive up prices, leading to inflation. Conversely, low GDP growth (a sluggish economy) can lead to higher unemployment as businesses cut back on hiring, but it might also curb inflation due to reduced consumer spending. It’s a delicate balancing act, akin to juggling chainsaws while riding a unicycle – impressive if you can pull it off, disastrous if you don’t.

Illustrative Diagram of Macroeconomic Indicator Interrelationships

Imagine a triangle.

Vertex 1: GDP (Gross Domestic Product) – Represents the total value of goods and services produced within a country’s borders in a specific period. It’s the big picture, the overall health of the economy.

Vertex 2: Inflation – Represents the rate at which the general level of prices for goods and services is rising, and subsequently, purchasing power is falling. Think of it as the economy’s fever – a high temperature signals something’s amiss.

Vertex 3: Unemployment – Represents the percentage of the labor force that is actively seeking employment but unable to find it. It’s a measure of the economy’s ability to provide jobs for its citizens.

Connections:

GDP ↑ → Inflation ↑: Increased GDP often leads to higher demand, pushing up prices (demand-pull inflation). Think of a sudden surge in popularity for avocado toast – increased demand leads to higher prices.

GDP ↑ → Unemployment ↓: A growing economy creates more jobs, reducing unemployment. The construction boom following a major natural disaster is a good example.

Inflation ↑ → Unemployment (potentially) ↑: High inflation can lead to decreased consumer spending and investment, potentially slowing economic growth and increasing unemployment (cost-push inflation). Imagine runaway inflation making everything prohibitively expensive; businesses may cut back, leading to job losses.

Unemployment ↑ → GDP ↓: High unemployment reduces consumer spending and overall economic activity, leading to lower GDP. The Great Depression is a stark example of this relationship.

Unemployment ↓ → Inflation (potentially) ↑: Low unemployment can lead to increased wages and production costs, contributing to inflation. The “Roaring Twenties” in the US, while experiencing prosperity, also saw significant inflationary pressures.

Using Economic Indicators for Decision-Making

Economic indicators, those quirky numerical snapshots of the economy, aren’t just for economists huddled in dimly lit offices. They’re powerful tools that, when wielded correctly, can help businesses make smarter decisions and individuals navigate the financial landscape with more confidence (and less accidental bankruptcy). Think of them as your crystal ball, albeit one that shows slightly blurry images of the future and occasionally predicts a recession when it’s actually just a particularly bad Tuesday for the stock market.

Businesses Employ Economic Indicators for Strategic Planning

Businesses of all sizes utilize economic indicators to inform their strategic planning. For example, a construction company might monitor housing starts (a leading indicator) to anticipate future demand for their services. If housing starts are rising, they might invest in expanding their workforce or acquiring new equipment. Conversely, a drop in housing starts could signal a need to cut costs or postpone expansion plans. Similarly, manufacturers track inflation rates to adjust pricing strategies, while retailers use consumer confidence indices to predict sales and inventory needs. Ignoring these signals is like navigating a stormy sea without a compass – potentially disastrous.

Businesses Using Economic Indicators

The use of economic indicators isn’t just about reacting to current trends; it’s about proactive strategic planning. A company might use leading indicators, such as consumer confidence or manufacturing orders, to anticipate future demand and adjust production accordingly. Lagging indicators, like unemployment rates, can help assess the overall health of the economy and inform decisions on hiring, investment, and expansion. Even coincident indicators, like GDP growth, provide a real-time snapshot of the economic situation, influencing short-term decisions such as pricing and marketing strategies. A robust understanding of these indicators empowers businesses to make informed choices, improving their chances of success in a constantly evolving market.

Individuals Using Economic Indicators for Financial Decisions

While businesses have teams dedicated to economic analysis, individuals can also benefit from understanding key indicators. For instance, monitoring inflation helps individuals adjust their budgets and investment strategies. A rise in inflation erodes purchasing power, making it crucial to adapt spending habits and potentially shift investments towards assets that can hedge against inflation. Similarly, understanding interest rate trends can guide decisions on borrowing and saving. Low interest rates might be a good time to take out a mortgage or make a large purchase, while high rates might encourage saving or investing in higher-yielding assets. It’s like having a personal financial advisor, albeit one that speaks mostly in percentages and graphs.

Limitations of Relying Solely on Economic Indicators

While economic indicators are valuable, it’s crucial to remember they are not a crystal ball. They offer a general overview of the economy, but they may not capture the nuances of specific industries or individual situations. Furthermore, indicators are often subject to revision and can be influenced by various factors, including statistical methodologies and unexpected events (like a global pandemic or a sudden surge in demand for novelty socks). Over-reliance on indicators without considering other qualitative factors can lead to flawed decisions. In short, economic indicators are a useful tool, but they should be used in conjunction with other forms of analysis, not as a sole source of truth.

Case Study: The Housing Market Crash of 2008

The 2008 housing market crash serves as a stark reminder of the limitations of relying solely on economic indicators. While indicators like housing starts initially painted a rosy picture of a booming market, other factors, such as subprime lending practices and lax regulatory oversight, were not fully reflected in the available data. The resulting crash demonstrated the importance of considering a broader range of factors beyond simple economic indicators when making significant financial decisions. The lesson learned? Economic indicators are a piece of the puzzle, but not the entire picture. Ignoring other crucial elements can lead to catastrophic consequences.

Resources for Finding Economic Data

Navigating the world of economic data can feel like searching for the legendary lost city of El Dorado – exciting, potentially rewarding, but also fraught with peril if you stumble into unreliable sources. Fear not, intrepid data explorer! This section provides a treasure map to help you locate the most reliable and relevant economic information. We’ll cover where to find it, what formats it comes in, and – crucially – how to avoid getting lost in a swamp of misleading statistics.

Economic data is available in a plethora of formats, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. You might find it presented in simple tables, detailed spreadsheets, visually engaging charts and graphs, or even within complex econometric models. Understanding the format is crucial to properly interpreting the data. For example, a simple line graph showing GDP growth over time provides a quick visual overview, while a detailed spreadsheet might provide the underlying data necessary for more in-depth analysis. Choosing the right format depends entirely on your needs and analytical skills. Remember, a picture is worth a thousand data points…but only if the picture is accurate!

Reliable Sources of Economic Data

The reliability of your data source is paramount. Using flawed data leads to flawed conclusions, a recipe for economic disaster (or at least, a very embarrassing presentation). Government agencies are generally considered reliable sources, but even they can sometimes have biases or methodological quirks. Independent research institutions and reputable financial institutions also provide valuable data, but always check their methodology and potential conflicts of interest.

Data Formats

Economic data is typically available in several formats: time series data (tracking a variable over time), cross-sectional data (comparing different entities at a single point in time), panel data (combining time series and cross-sectional data), and raw data (the unprocessed numbers). The choice of format depends on the type of analysis you are conducting. For instance, forecasting future trends might require time series data, while comparing economic performance across different countries might call for cross-sectional data. Choosing the wrong format is like trying to build a house with only toothpicks – it might look interesting, but it won’t stand the test of time.

Critical Evaluation of Data Sources and Methodology

Before accepting any economic data at face value, consider the source’s reputation, potential biases, and the methodology used to collect and process the data. A well-respected institution using rigorous methodology is far more trustworthy than an anonymous blog post citing questionable sources. Look for clear explanations of data collection methods, sample sizes, and potential limitations. Remember, even the most prestigious organizations can make mistakes; critical thinking is your best defense against misleading information. Treat every data point with the healthy skepticism you’d apply to a politician’s campaign promise.

Reputable Sources of Economic Data

| Source | Data Offered | Accessibility |

|---|---|---|

| Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) – USA | GDP, personal income, employment data, etc. | Mostly free and publicly available online |

| Federal Reserve (FED) – USA | Monetary policy data, interest rates, inflation data, etc. | Mostly free and publicly available online |

| International Monetary Fund (IMF) | Global economic data, country-specific reports, forecasts | Much data freely available online; some reports require subscriptions |

| World Bank | Global development indicators, poverty data, economic growth statistics | Much data freely available online; some reports require subscriptions |

| Bloomberg (Subscription Based) | Extensive financial data, market analysis, economic forecasts | Requires a subscription; costly but comprehensive |

Final Summary

And there you have it! We’ve navigated the sometimes-treacherous, often-amusing terrain of economic indicators. While predicting the future with perfect accuracy remains elusive (even for the most seasoned economists), understanding these indicators empowers you to make more informed decisions, both personally and professionally. Remember, even a slightly improved understanding can save you from some seriously cringe-worthy financial blunders. So go forth, armed with your newfound knowledge, and may your economic forecasting adventures be filled with laughter (and hopefully, profit!).

Essential FAQs

What’s the difference between nominal and real GDP?

Nominal GDP is the value of goods and services produced in a year using current prices, while real GDP adjusts for inflation, providing a clearer picture of actual economic growth.

How often are economic indicators released?

It varies greatly depending on the indicator. Some, like the unemployment rate, are monthly; others, like GDP, are quarterly or even annually. Think of it as an economic soap opera – some episodes are weekly cliffhangers, others are drawn-out season finales.

Can I use economic indicators to predict the stock market?

While some indicators correlate with stock market performance, it’s far from a perfect science. Many other factors influence stock prices, making it unwise to rely solely on economic indicators for investment decisions. Consider it more of a helpful hint than a crystal ball.