Understanding a company’s financial health is crucial for investors, creditors, and even internal management. Financial statement analysis provides the tools to dissect key financial documents—the balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement—uncovering insights into profitability, liquidity, solvency, and overall operational efficiency. This guide offers a practical approach to mastering these analytical techniques, equipping you with the skills to interpret financial data and make informed decisions.

From calculating essential ratios like liquidity and profitability metrics to employing advanced techniques such as vertical and horizontal analysis, we will explore the nuances of interpreting financial statements. We’ll delve into the significance of each statement, highlighting potential red flags and areas for improvement. This comprehensive approach will empower you to navigate the complexities of financial reporting and utilize this information effectively.

Introduction to Financial Statement Examination

Financial statement examination is the systematic process of reviewing a company’s financial records to assess its financial health, performance, and compliance with accounting standards. This in-depth analysis goes beyond simply looking at the numbers; it involves interpreting the data to understand the underlying trends and potential risks.

The purpose of scrutinizing financial statements is multifaceted. It provides stakeholders – including investors, creditors, management, and regulatory bodies – with a comprehensive understanding of a company’s financial position. This understanding is crucial for making informed decisions regarding investment, lending, operational strategies, and regulatory compliance. A thorough examination can identify areas of strength and weakness, highlight potential problems before they escalate, and ultimately contribute to better financial management and improved profitability.

Types of Financial Statements Used in Examination

Financial statement examination utilizes several key financial statements to provide a holistic view of a company’s financial health. These statements, prepared in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) or International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), offer different perspectives on the company’s financial performance.

- Balance Sheet: This statement provides a snapshot of a company’s assets, liabilities, and equity at a specific point in time. It shows what a company owns (assets), what it owes (liabilities), and the difference between the two (equity).

- Income Statement: This statement shows a company’s revenues, expenses, and profits over a specific period. It reveals the company’s profitability and operational efficiency.

- Statement of Cash Flows: This statement tracks the movement of cash both into and out of a company over a specific period. It provides insights into a company’s liquidity and its ability to meet its financial obligations.

- Statement of Changes in Equity: This statement details the changes in a company’s equity over a period, including contributions from owners, net income, and dividends.

Businesses Benefiting from Financial Statement Examination

The benefits of thorough financial statement examination extend across various business types and sizes. Large corporations rely on detailed analysis to support strategic decision-making, attract investors, and ensure regulatory compliance. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) can use financial statement analysis to identify areas for cost reduction, improve cash flow management, and secure funding.

For example, a rapidly growing tech startup might use financial statement analysis to secure venture capital funding by demonstrating its potential for profitability. A mature manufacturing company could use it to assess the efficiency of its operations and identify opportunities for cost savings. Similarly, a retail business might utilize this analysis to understand seasonal sales patterns and optimize inventory management. Even non-profit organizations benefit from examining their financial statements to ensure they are meeting their financial goals and using their resources effectively.

Ratio Analysis Techniques

Ratio analysis is a crucial tool in financial statement analysis, providing insights into a company’s performance, financial health, and operational efficiency. By examining the relationships between different financial statement items, we can derive meaningful conclusions about a company’s strengths and weaknesses, and compare its performance to industry benchmarks or previous periods. This analysis goes beyond simply looking at individual figures, offering a more holistic understanding of the business’s financial position.

Categories of Financial Ratios

Financial ratios are broadly categorized into four main groups: liquidity, profitability, solvency, and activity ratios. Each category provides a different perspective on the company’s financial performance. Understanding the nuances of each category allows for a comprehensive assessment.

Liquidity Ratios

Liquidity ratios measure a company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations. A key indicator is the current ratio, which assesses whether a company possesses enough liquid assets to cover its current liabilities. Low liquidity can signal potential financial distress. Conversely, excessively high liquidity might indicate inefficient use of assets.

Profitability Ratios

Profitability ratios evaluate a company’s ability to generate profits from its operations and investments. These ratios assess the efficiency of a company in utilizing its assets and generating returns for its shareholders. Key profitability ratios include gross profit margin, net profit margin, and return on assets (ROA). A declining profitability ratio can signal operational inefficiencies or weakening market conditions.

Solvency Ratios

Solvency ratios measure a company’s ability to meet its long-term obligations. These ratios provide insights into a company’s financial leverage and its ability to withstand financial pressures. A key indicator is the debt-to-equity ratio, which reveals the proportion of a company’s financing from debt compared to equity. High debt levels can increase financial risk.

Activity Ratios

Activity ratios, also known as efficiency ratios, measure how effectively a company manages its assets and liabilities. These ratios assess the speed at which a company converts its assets into cash or sales. Key activity ratios include inventory turnover, accounts receivable turnover, and asset turnover. Low turnover ratios can indicate inefficient management of resources.

Calculating Key Ratios

Several key ratios are frequently used in financial analysis. Their calculation and interpretation provide valuable insights into a company’s financial health.

Current Ratio = Current Assets / Current Liabilities

The current ratio measures a company’s ability to pay its short-term liabilities with its short-term assets. A ratio of 2.0 or higher is generally considered healthy, indicating ample liquidity. A ratio below 1.0 suggests potential liquidity problems. For example, a company with current assets of $100,000 and current liabilities of $50,000 has a current ratio of 2.0.

Debt-to-Equity Ratio = Total Debt / Total Equity

The debt-to-equity ratio indicates the proportion of a company’s financing that comes from debt relative to equity. A higher ratio suggests higher financial risk, as the company relies more on debt financing. A ratio of 1.0 indicates that debt and equity are equal. A company with $50,000 in debt and $100,000 in equity has a debt-to-equity ratio of 0.5.

Return on Assets (ROA) = Net Income / Total Assets

ROA measures how efficiently a company uses its assets to generate profit. A higher ROA indicates better asset utilization and profitability. A company with a net income of $20,000 and total assets of $100,000 has an ROA of 20%.

Comparison of Ratio Analysis Techniques

Different ratio analysis techniques offer distinct perspectives on a company’s financial health. While each provides valuable information, their interpretation should be considered in context, comparing results across multiple periods and industry benchmarks. Over-reliance on a single ratio can lead to misleading conclusions. For example, a high current ratio might be misleading if a significant portion of the current assets consists of obsolete inventory.

Common Financial Ratios

| Ratio | Formula | Interpretation | Impact of Different Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Ratio | Current Assets / Current Liabilities | Measures short-term liquidity | High: Strong liquidity; Low: Potential liquidity issues |

| Debt-to-Equity Ratio | Total Debt / Total Equity | Measures financial leverage | High: Higher financial risk; Low: Lower financial risk |

| Return on Assets (ROA) | Net Income / Total Assets | Measures profitability relative to assets | High: Efficient asset utilization; Low: Inefficient asset utilization |

| Profit Margin | Net Income / Revenue | Measures profitability relative to revenue | High: High profitability; Low: Low profitability |

Analyzing the Balance Sheet

The balance sheet, a snapshot of a company’s financial position at a specific point in time, provides crucial insights into its assets, liabilities, and equity. Analyzing this statement allows investors and creditors to assess a company’s liquidity, solvency, and overall financial health. Understanding the interplay between these components is key to a comprehensive financial assessment.

Key Balance Sheet Components and Their Significance

The balance sheet is structured around the fundamental accounting equation: Assets = Liabilities + Equity. Assets represent what a company owns (e.g., cash, accounts receivable, inventory, property, plant, and equipment), while liabilities represent what it owes (e.g., accounts payable, loans, bonds payable). Equity represents the owners’ stake in the company (shareholders’ equity). Each component provides vital information about the company’s operational efficiency, financial strength, and future prospects. For instance, a high level of current assets relative to current liabilities indicates strong short-term liquidity, while a significant proportion of long-term assets might signal a commitment to long-term growth but also potential higher risk. Similarly, a high level of equity suggests a strong financial foundation, reducing reliance on debt financing.

Evaluating Liquidity and Solvency

Liquidity refers to a company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations, while solvency refers to its ability to meet its long-term obligations. Several ratios derived from balance sheet data help assess these aspects. The current ratio (Current Assets / Current Liabilities) is a common measure of liquidity. A ratio significantly above 1 suggests strong liquidity, while a ratio below 1 might indicate potential short-term financial difficulties. The quick ratio ((Current Assets – Inventory) / Current Liabilities) provides a more conservative measure of liquidity by excluding inventory, which may not be easily converted to cash. Solvency is often assessed using debt-to-equity ratio (Total Debt / Total Equity), which indicates the proportion of financing derived from debt versus equity. A high debt-to-equity ratio suggests higher financial risk. Another important indicator is the debt-to-asset ratio (Total Debt / Total Assets), reflecting the overall proportion of assets financed by debt. For example, a company with a high debt-to-asset ratio might face challenges in meeting its obligations during economic downturns.

Analyzing Balance Sheet Changes Over Time

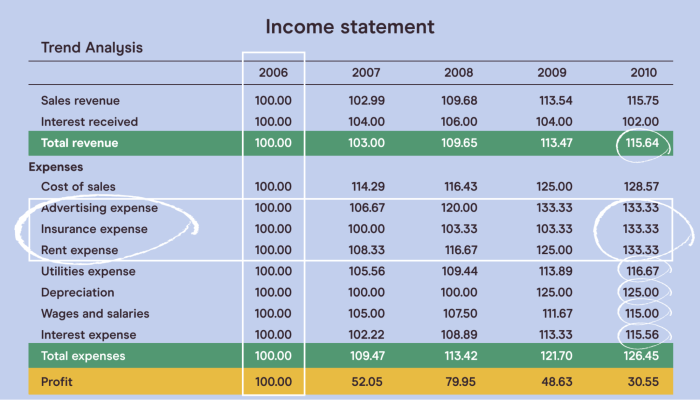

Trend analysis involves comparing balance sheet data over several periods to identify patterns and trends. This allows for the assessment of a company’s financial performance and its growth trajectory. For instance, a consistent increase in accounts receivable over time might indicate problems with collecting payments from customers. Similarly, a continuous rise in long-term debt could suggest increased financial leverage and potential risks. Analyzing the growth rate of assets, liabilities, and equity provides insights into a company’s overall financial health and its ability to generate and manage resources effectively. Presenting this data in a comparative table, showing percentage changes year-over-year, provides a clear picture of the trends.

Identifying Potential Red Flags on a Balance Sheet

Analyzing the balance sheet for potential red flags requires careful examination of various aspects. Several indicators warrant close scrutiny:

- High Debt Levels: A consistently high debt-to-equity or debt-to-asset ratio can signal excessive reliance on debt financing, increasing financial risk.

- Increasing Accounts Receivable: A significant and sustained increase in accounts receivable may indicate difficulties in collecting payments from customers, potentially leading to cash flow problems.

- High Inventory Levels: Excessive inventory buildup can signal weak sales, obsolete products, or inefficient inventory management, impacting profitability and liquidity.

- Decreasing Current Ratio: A declining current ratio suggests worsening liquidity, making it harder to meet short-term obligations.

- Significant Increase in Liabilities: A rapid increase in liabilities, particularly short-term debt, can indicate financial distress.

- Negative Net Worth: If liabilities exceed assets, the company has a negative net worth, signaling potential insolvency.

- Unusual Changes in Asset Composition: Significant and unexplained changes in the composition of assets warrant further investigation. For instance, a sudden increase in intangible assets without a corresponding increase in revenue might raise concerns.

Analyzing the Income Statement

The income statement, also known as the profit and loss (P&L) statement, provides a snapshot of a company’s financial performance over a specific period. Understanding its components is crucial for evaluating profitability and making informed business decisions. This section delves into the key elements of the income statement and explores methods for assessing profitability.

Income Statement Components and Their Importance

The income statement typically presents revenues, cost of goods sold (COGS), gross profit, operating expenses, operating income, other income and expenses, and finally, net income. Each component plays a vital role in understanding the company’s profitability at different stages of its operations. Revenues represent the total sales generated during the period. COGS represents the direct costs associated with producing goods sold. The difference between revenue and COGS is the gross profit, a key indicator of a company’s pricing strategy and production efficiency. Operating expenses encompass costs incurred in running the business, such as salaries, rent, and utilities. Subtracting operating expenses from gross profit yields operating income, which reflects profitability from core business activities. Other income and expenses account for non-operating items, such as investment income or interest expenses. Finally, net income represents the company’s overall profit after all expenses are deducted.

Profitability Assessment Methods

Several key ratios derived from the income statement help assess profitability. These ratios provide insights into different aspects of a company’s performance and allow for comparison across time and with competitors.

Gross Profit Margin

The gross profit margin is calculated as:

Gross Profit Margin = (Revenue – Cost of Goods Sold) / Revenue * 100%

This ratio indicates the percentage of revenue remaining after covering the direct costs of production. A higher gross profit margin suggests greater efficiency in production or pricing power. For example, a company with a 40% gross profit margin retains 40 cents for every dollar of revenue generated after covering COGS.

Operating Profit Margin

The operating profit margin is calculated as:

Operating Profit Margin = Operating Income / Revenue * 100%

This ratio measures the profitability of a company’s core operations after accounting for both direct and indirect costs. A higher operating profit margin indicates greater efficiency in managing operating expenses. A company with a 20% operating profit margin generates 20 cents of operating profit for every dollar of revenue.

Net Profit Margin

The net profit margin is calculated as:

Net Profit Margin = Net Income / Revenue * 100%

This ratio represents the overall profitability of the company after all expenses, including taxes and interest, are considered. A higher net profit margin indicates superior overall financial health and efficiency. A company with a 10% net profit margin retains 10 cents of profit for every dollar of revenue.

Comparing Profitability Metrics

While all three margins are valuable, they offer different perspectives. The gross profit margin focuses solely on production efficiency and pricing, while the operating profit margin incorporates operating expenses, providing a broader view of operational efficiency. The net profit margin offers the most comprehensive view, reflecting the overall profitability after all expenses are considered. Analyzing these ratios together provides a more complete understanding of a company’s profitability.

Analyzing the Income Statement: A Step-by-Step Procedure

A systematic approach is crucial for effective income statement analysis. The following steps can help identify areas of strength and weakness:

- Horizontal Analysis: Compare each line item over multiple periods (e.g., year-over-year) to identify trends and changes in revenue, costs, and profits. This helps reveal growth patterns or potential problems.

- Vertical Analysis: Express each line item as a percentage of revenue. This allows for comparison of the relative importance of different cost categories and assessment of profitability ratios across periods.

- Ratio Analysis: Calculate and analyze gross profit margin, operating profit margin, and net profit margin to assess profitability at different stages of the business process. Compare these ratios to industry benchmarks or competitors.

- Trend Analysis: Identify long-term trends in key profitability ratios to understand the company’s performance over time and predict future performance.

- Benchmarking: Compare the company’s profitability ratios to those of its competitors or industry averages to assess its relative performance and identify areas for improvement.

Analyzing the Cash Flow Statement

The cash flow statement provides a crucial insight into a company’s liquidity and ability to generate cash, complementing the information presented in the income statement and balance sheet. Unlike the accrual-based income statement, the cash flow statement focuses solely on the actual cash inflows and outflows during a specific period. This makes it an invaluable tool for assessing a company’s financial health and predicting its future performance.

The cash flow statement is structured to categorize cash flows into three main sections: operating activities, investing activities, and financing activities. Understanding the dynamics within each section allows for a comprehensive assessment of a company’s cash management and overall financial strength.

Cash Flow from Operating Activities

This section details the cash generated or used by the company’s core business operations. It reflects the cash inflows from sales and other operating revenues, and the cash outflows for expenses such as cost of goods sold, salaries, rent, and taxes. Analyzing this section reveals the company’s efficiency in managing its day-to-day operations and generating cash from its primary business activities. A consistently strong positive cash flow from operations indicates a healthy and sustainable business model. Conversely, consistently negative cash flow from operations could signal underlying problems with profitability or efficiency. Analyzing changes in working capital (accounts receivable, inventory, accounts payable) within this section is crucial for understanding the reasons behind variations in cash flow. For example, a significant increase in accounts receivable might suggest slower collection times and reduced cash inflows.

Cash Flow from Investing Activities

This section reports cash flows related to the acquisition and disposal of long-term assets, such as property, plant, and equipment (PP&E), investments in other companies, and acquisitions. Positive cash flow indicates that the company is selling assets or making successful investments, while negative cash flow signifies capital expenditures (CapEx) or investments in growth opportunities. Analyzing this section helps assess a company’s investment strategy and its commitment to growth and long-term value creation. For instance, significant capital expenditures might suggest the company is investing in expansion or modernization, potentially leading to future growth. Conversely, a lack of investment could signal a lack of growth opportunities or a more conservative approach.

Cash Flow from Financing Activities

This section shows the cash flows related to financing the company’s operations. It includes cash inflows from issuing debt or equity, and cash outflows for debt repayments, dividend payments, and share repurchases. Analyzing this section reveals the company’s capital structure and its reliance on debt or equity financing. A company with consistently strong cash flow from operations might have more flexibility in its financing activities. For example, a company might use excess cash flow from operations to repay debt, reducing its financial risk. Conversely, a company heavily reliant on debt financing might face difficulties in meeting its debt obligations if its operating cash flow is weak.

Examples of Cash Flow Statement Analysis Insights

Analyzing the cash flow statement can reveal critical insights. For example, a company might report high net income but low cash flow from operations, suggesting potential issues with accounts receivable or inventory management. Conversely, a company with strong operating cash flow but significant capital expenditures might be investing heavily in future growth, even if it temporarily impacts profitability. Comparing a company’s cash flow trends over time and against industry peers can provide valuable context and help identify potential strengths or weaknesses. A consistent increase in operating cash flow demonstrates strong operational performance and a healthy financial position, while a decline might signal weakening business fundamentals or emerging challenges.

Vertical and Horizontal Analysis

Financial statement analysis employs several techniques to uncover trends and assess a company’s financial health. Vertical and horizontal analysis are two fundamental methods that provide valuable insights into a company’s performance over time and its relative proportions of assets, liabilities, and equity. These analyses help in identifying areas of strength and weakness, facilitating informed decision-making.

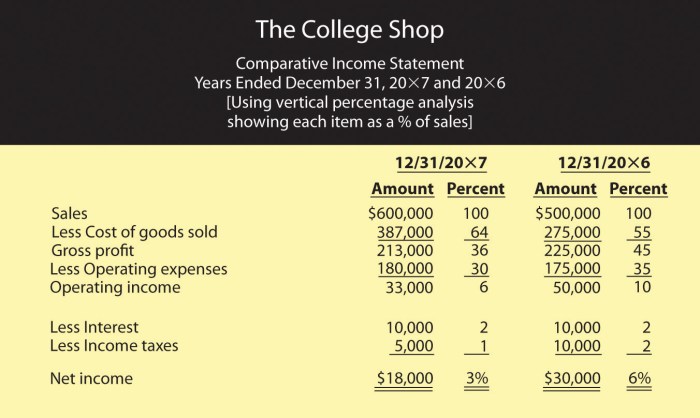

Vertical analysis expresses each line item in a financial statement as a percentage of a base figure. Horizontal analysis, conversely, compares line items across different periods to show growth or decline. Both techniques, when used together, offer a comprehensive understanding of a company’s financial performance.

Vertical Analysis

Vertical analysis presents each item on a financial statement as a percentage of a base amount. For the balance sheet, total assets are the base, while for the income statement, net sales or revenue serve as the base. This allows for a clear comparison of the relative importance of each item within the statement, irrespective of the overall size of the company.

To perform vertical analysis on a balance sheet, each asset, liability, and equity account is divided by total assets and multiplied by 100%. Similarly, for an income statement, each expense and revenue item is divided by net sales (or revenue) and multiplied by 100%. This transforms absolute figures into percentages, revealing the proportion each item contributes to the total. For example, if cost of goods sold is 60% of net sales, this highlights a significant portion of revenue dedicated to production.

Horizontal Analysis

Horizontal analysis, also known as trend analysis, compares financial data from different periods to reveal changes over time. This allows for the identification of trends and patterns in a company’s financial performance. Each item in a subsequent period is compared to the same item in a base period, and the difference is expressed as a percentage change.

To conduct horizontal analysis on a balance sheet or income statement, select a base year. Then, for each subsequent year, calculate the percentage change for each line item compared to the base year. The formula is: [(Current Year Amount – Base Year Amount) / Base Year Amount] * 100%. A positive percentage indicates growth, while a negative percentage indicates a decline. For instance, a 10% increase in sales from one year to the next suggests positive sales growth.

Comparison of Vertical and Horizontal Analysis

Vertical and horizontal analyses are complementary techniques. Vertical analysis provides a snapshot of a company’s financial structure at a specific point in time, showing the relative proportions of different items. Horizontal analysis, on the other hand, examines changes in these proportions and the overall financial performance over time. Using both methods allows for a more thorough and insightful analysis. For example, vertical analysis might reveal that cost of goods sold is consistently high relative to sales, while horizontal analysis could reveal that this percentage has been increasing over time, indicating a potential problem that needs attention.

Sample Vertical and Horizontal Analysis of a Simplified Income Statement

Let’s consider a simplified income statement for Company X for two years:

Company X Income Statement

| Item | Year 1 | Year 2 |

|————————–|————|————|

| Net Sales | $100,000 | $120,000 |

| Cost of Goods Sold | $60,000 | $70,000 |

| Gross Profit | $40,000 | $50,000 |

| Operating Expenses | $20,000 | $25,000 |

| Operating Income | $20,000 | $25,000 |

| Net Income | $15,000 | $20,000 |

Vertical Analysis (Year 1 as base): Year 1 would show all items as percentages of $100,000 (Net Sales). For example, Cost of Goods Sold would be 60% ($60,000/$100,000 * 100%). Year 2 would show all items as percentages of $120,000.

Horizontal Analysis (Year 1 as base): For each item, the percentage change from Year 1 to Year 2 would be calculated. For example, the percentage change in Net Sales would be [(120,000 – 100,000) / 100,000] * 100% = 20%. This indicates a 20% increase in net sales. Similar calculations would be done for each line item. The resulting table would show the percentage change for each item from Year 1 to Year 2. A positive percentage indicates growth, while a negative percentage shows decline.

Common-Size Statements

Common-size statements are a valuable tool in financial statement analysis, providing a standardized way to compare financial data across different periods or between companies of varying sizes. By expressing each line item as a percentage of a base figure, common-size statements eliminate the scale differences and allow for a more meaningful comparison of financial performance and structure.

Common-size statements normalize financial data, facilitating easier identification of trends and anomalies that might be obscured by raw figures. This normalization is particularly useful when analyzing companies with significantly different asset bases or revenue streams.

Creating Common-Size Balance Sheets

To create a common-size balance sheet, each asset, liability, and equity account is expressed as a percentage of total assets. This means dividing each individual line item by the total assets and multiplying by 100 to express it as a percentage. For example, if a company has total assets of $1,000,000 and cash of $100,000, the common-size percentage for cash would be (100,000/1,000,000) * 100 = 10%. This process is repeated for all balance sheet items. The resulting statement shows the relative proportion of each asset, liability, and equity item to the total assets, allowing for easier comparison across different periods or companies. Analyzing these percentages reveals insights into the company’s capital structure, liquidity, and solvency. A consistently high percentage of debt, for instance, might indicate a higher risk profile.

Creating Common-Size Income Statements

Similarly, a common-size income statement expresses each revenue and expense item as a percentage of net sales (or revenue). Each line item is divided by net sales and multiplied by 100. For example, if a company has net sales of $500,000 and cost of goods sold of $300,000, the common-size percentage for cost of goods sold would be (300,000/500,000) * 100 = 60%. This provides a clear picture of the company’s profitability ratios and the relative contribution of each expense category to the overall cost structure. Changes in these percentages over time can signal shifts in operating efficiency or pricing strategies.

Benefits of Common-Size Statements for Comparative Analysis

Common-size statements offer several key benefits for comparative analysis. First, they allow for the comparison of companies of different sizes. A large company and a small company in the same industry can be directly compared based on the percentage of each item to total assets or revenue, rather than being hampered by the difference in absolute values. Second, they facilitate trend analysis over time. By comparing common-size statements for multiple years, a company can identify changes in its financial structure and performance, such as an increase in debt or a decrease in profit margins. Finally, they help in identifying anomalies or outliers in the financial data. Significant deviations from the norm can be more easily spotted when comparing common-size percentages.

Examples of Identifying Trends and Anomalies

Consider a company whose common-size income statement shows a consistent increase in the percentage of selling, general, and administrative expenses over several years. This trend, while not immediately apparent in the raw financial data, signals a potential area of concern requiring further investigation. Similarly, a sudden decrease in the percentage of accounts receivable on a common-size balance sheet could indicate improved collection efforts or potentially a decline in sales. Conversely, a sharp increase might suggest problems with credit management. By comparing common-size statements across different periods and with industry averages, analysts can identify these trends and anomalies more efficiently, leading to more informed decisions.

Last Point

Mastering financial statement analysis is not just about crunching numbers; it’s about developing a keen understanding of a company’s financial story. By applying the techniques Artikeld in this guide, you’ll gain the ability to assess risk, identify opportunities, and make data-driven decisions with greater confidence. Whether you’re an investor, a business owner, or a financial professional, the ability to interpret financial statements accurately is an invaluable asset in today’s dynamic economic landscape. This skill empowers informed choices, driving success and mitigating potential pitfalls.

Common Queries

What is the difference between vertical and horizontal analysis?

Vertical analysis compares line items within a single financial statement as a percentage of a base figure (e.g., total assets on the balance sheet or net sales on the income statement). Horizontal analysis compares line items across multiple periods to identify trends and changes over time.

How can I use financial statement analysis to identify potential fraud?

Analyzing unusual fluctuations in key ratios, inconsistencies between different statements, and unexplained discrepancies in account balances can help reveal potential fraudulent activities. Looking for patterns of unusual transactions or significant changes in accounting practices is also important.

What are some limitations of financial statement analysis?

Financial statements can be manipulated, and the analysis relies on historical data, which may not accurately predict future performance. The analysis also often overlooks qualitative factors such as management quality and industry trends.

How frequently should financial statements be analyzed?

The frequency depends on the context. For investment decisions, regular monitoring (quarterly or even monthly) is crucial. For internal management, analysis can be performed monthly, quarterly, or annually, depending on the business needs.