Unlocking the secrets hidden within a company’s financial statements is key to informed decision-making. Whether you’re an investor seeking promising ventures, a creditor assessing risk, or a manager striving for operational excellence, understanding financial statement analysis is paramount. This guide provides a comprehensive exploration of interpreting balance sheets, income statements, and cash flow statements, equipping you with the tools to analyze a company’s financial health and future prospects. We’ll delve into ratio analysis, trend analysis, and even explore the detection of potential financial statement fraud.

This journey will cover a range of techniques, from calculating key financial ratios and interpreting their implications across various industries to utilizing common-size statements and trend analysis for a deeper understanding of a company’s performance over time. We will also touch upon the use of financial statements for forecasting future performance, highlighting both the potential and the limitations of such predictions. The goal is to empower you with the knowledge and skills to confidently navigate the complexities of financial reporting.

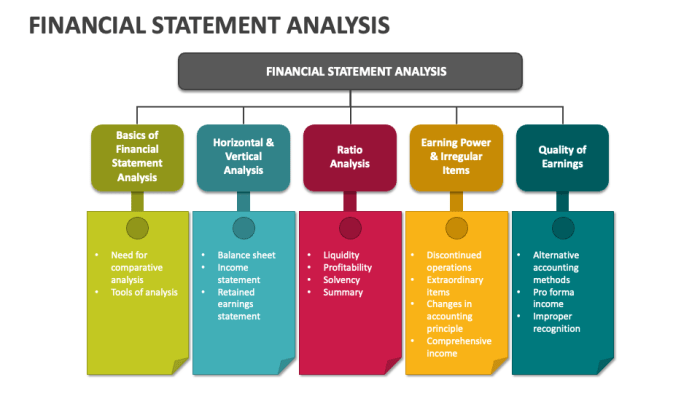

Introduction to Financial Statement Interpretation

Financial statement interpretation is the process of analyzing a company’s financial statements—the balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement—to understand its financial performance, position, and prospects. This process is crucial for various stakeholders, each with their own specific interests and perspectives. Effective interpretation provides insights that inform critical decisions.

Financial statement interpretation provides valuable insights for different stakeholders. Investors use this information to assess a company’s profitability, solvency, and growth potential before making investment decisions. Creditors, such as banks and bondholders, rely on financial statement analysis to evaluate a company’s creditworthiness and ability to repay loans. Management utilizes this analysis for internal planning, performance monitoring, and strategic decision-making, identifying areas for improvement and opportunities for growth.

Limitations of Using Financial Statements Alone for Decision-Making

While financial statements are essential tools, relying solely on them for decision-making can be misleading. Financial statements present a historical view of a company’s performance, not a prediction of future results. They may not capture qualitative factors such as management quality, employee morale, or the impact of unforeseen events like natural disasters or economic downturns. Furthermore, the information presented can be manipulated through accounting practices, leading to a distorted picture of the company’s true financial health. A comprehensive analysis requires considering additional information, such as industry benchmarks, macroeconomic conditions, and qualitative assessments. For example, a company might appear highly profitable based on its income statement, but a deeper analysis might reveal high levels of debt or declining sales trends that indicate future financial instability.

A Step-by-Step Guide to Interpreting Financial Statements

A systematic approach is crucial for effective financial statement interpretation. The process typically involves several key steps. First, gather all necessary financial statements for the period under review. This usually includes the balance sheet, income statement, and statement of cash flows for at least the last three to five years. Second, perform a horizontal analysis, comparing financial data across different periods to identify trends and patterns. For instance, analyzing the growth rate of revenue or expenses over several years can reveal significant trends. Third, conduct a vertical analysis, expressing each line item as a percentage of a base figure (e.g., expressing each item on the income statement as a percentage of revenue) to understand the relative importance of each component. Fourth, calculate key financial ratios such as profitability ratios (gross profit margin, net profit margin), liquidity ratios (current ratio, quick ratio), and solvency ratios (debt-to-equity ratio). These ratios provide insights into different aspects of a company’s financial health. Fifth, compare the company’s performance to industry averages and competitors to assess its relative position within the market. Finally, integrate the quantitative analysis with qualitative information, such as industry trends, competitive landscape, and management’s strategic plans, to gain a holistic understanding of the company’s financial situation. For example, a high debt-to-equity ratio might be acceptable for a rapidly growing technology company but could be a significant red flag for a mature, stable utility company.

Ratio Analysis Techniques

Ratio analysis is a crucial tool in financial statement interpretation, providing a deeper understanding of a company’s financial health and performance than simply reviewing the statements themselves. By comparing different line items within the financial statements, we can derive meaningful insights into liquidity, solvency, profitability, and efficiency. This allows for both internal comparisons over time and external comparisons against industry competitors or benchmarks.

Ratio analysis involves calculating various ratios, each offering a specific perspective on a company’s financial standing. Understanding the strengths and weaknesses of each ratio type is key to a comprehensive analysis.

Types of Financial Ratios and Their Comparison

Financial ratios are broadly categorized into four main types: liquidity, solvency, profitability, and efficiency. Each category focuses on a different aspect of a company’s financial performance and risk profile. Understanding the differences between these categories is essential for a complete picture of a company’s financial health.

Liquidity ratios measure a company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations. Solvency ratios assess the company’s ability to meet its long-term obligations. Profitability ratios evaluate a company’s ability to generate profits from its operations. Finally, efficiency ratios examine how effectively a company manages its assets and liabilities. While distinct, these categories are interconnected; for instance, high profitability can improve liquidity and solvency. A comprehensive analysis considers all four types.

Examples of Ratio Calculation and Interpretation Across Industries

The interpretation of a ratio’s value is highly context-dependent, varying significantly across industries. For example, a high inventory turnover ratio is generally positive, indicating efficient inventory management. However, this could be negative for a luxury goods retailer where a slower turnover is expected due to higher prices and lower volume. Similarly, a high debt-to-equity ratio might be acceptable for a capital-intensive industry like utilities but alarming for a technology startup.

Let’s consider a few examples. A retail company might have a high current ratio (a liquidity ratio) compared to a technology company, reflecting the difference in their operating cycles and asset structures. A manufacturing company might have a high asset turnover ratio (an efficiency ratio) compared to a service-based company, due to the tangible assets involved in manufacturing. Profitability ratios, like return on equity (ROE), will differ based on the industry’s average profitability and risk. A highly regulated utility company might have a lower ROE than a high-growth technology firm.

Key Financial Ratios: Formulas and Interpretations

The following table illustrates the formulas and interpretations of five key financial ratios, along with illustrative industry benchmarks (these are approximate and will vary depending on specific industry sub-segments and economic conditions).

| Ratio Name | Formula | Interpretation | Industry Benchmark (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Ratio | Current Assets / Current Liabilities | Measures short-term debt-paying ability. Higher is generally better, but too high might indicate inefficient asset utilization. | Retail: 1.5 – 2.5; Technology: 1.0 – 1.5 |

| Debt-to-Equity Ratio | Total Debt / Total Equity | Measures the proportion of financing from debt relative to equity. Higher ratios indicate higher financial risk. | Utilities: 1.0 – 2.0; Technology: 0.5 – 1.0 |

| Gross Profit Margin | (Revenue – Cost of Goods Sold) / Revenue | Measures profitability after considering direct costs. Higher is better, indicating efficient cost management. | Grocery: 25-35%; Technology: 60-75% |

| Return on Equity (ROE) | Net Income / Total Equity | Measures the return generated on shareholder investment. Higher is better, reflecting efficient use of equity capital. | Financials: 15-20%; Manufacturing: 10-15% |

| Inventory Turnover | Cost of Goods Sold / Average Inventory | Measures how efficiently inventory is managed. Higher generally indicates efficient inventory management, but can be industry-specific. | Grocery: 10-15x; Automotive: 2-4x |

Analyzing the Balance Sheet

The balance sheet, a cornerstone of financial statement analysis, provides a snapshot of a company’s financial position at a specific point in time. Unlike the income statement, which shows performance over a period, the balance sheet offers a static view of assets, liabilities, and equity. Analyzing this statement is crucial for understanding a company’s liquidity, solvency, and overall financial health. A thorough examination reveals the composition of a company’s resources and how they are financed, providing valuable insights for investors, creditors, and management alike.

Analyzing the balance sheet involves more than simply reviewing the figures; it requires understanding the relationships between different accounts and how these relationships change over time. This dynamic analysis is key to identifying trends and predicting future performance. For example, a consistent increase in accounts receivable might signal problems with collections, while a sharp rise in long-term debt could indicate increased financial risk.

Key Balance Sheet Elements and Their Significance

The balance sheet follows the fundamental accounting equation: Assets = Liabilities + Equity. Assets represent what a company owns, liabilities represent what it owes, and equity represents the owners’ stake in the company. Understanding the composition and relative proportions of each is critical. Current assets (cash, accounts receivable, inventory) represent resources that are expected to be converted to cash within one year. Fixed assets (property, plant, and equipment) represent long-term investments. Current liabilities (accounts payable, short-term debt) are obligations due within one year, while long-term liabilities (long-term debt, bonds payable) are obligations due beyond one year. Equity represents the residual interest in the assets after deducting liabilities. Analyzing the relationships between these elements, such as the current ratio (current assets / current liabilities) and the debt-to-equity ratio (total debt / total equity), provides crucial insights into a company’s financial health and risk profile. For instance, a high current ratio suggests strong liquidity, while a high debt-to-equity ratio indicates higher financial leverage and risk.

Analyzing Changes in the Balance Sheet Over Time

Comparing balance sheets from multiple periods allows for the identification of trends and patterns that may not be apparent from a single snapshot. Analyzing changes in individual accounts, such as increases or decreases in inventory, accounts receivable, or long-term debt, provides valuable insights into operational efficiency, creditworthiness, and financial strategy. For example, a consistent increase in inventory could indicate slow sales or inefficient inventory management, while a decrease in accounts receivable might suggest improved collections practices. By tracking these changes over time, analysts can better assess the company’s financial performance and predict future trends. This trend analysis is often supplemented by using common-size balance sheets, which express each item as a percentage of total assets, facilitating comparisons across different periods and companies of varying sizes.

Implications of High or Low Levels of Assets and Liabilities

Understanding the implications of high or low levels of different balance sheet items is crucial for a comprehensive analysis.

- High Current Assets: While seemingly positive, excessively high current assets (especially cash and inventory) can indicate inefficient use of resources. Excess cash may represent missed investment opportunities, while high inventory levels could suggest potential obsolescence or weak sales.

- Low Current Assets: Low current assets, particularly cash, can indicate liquidity problems and potential difficulties in meeting short-term obligations. This may lead to financial distress if not addressed.

- High Fixed Assets: A high level of fixed assets relative to sales might indicate overinvestment in capital assets or inefficient asset utilization. This can impact profitability and return on investment.

- Low Fixed Assets: Low fixed assets might restrict a company’s ability to expand or meet future production demands, potentially limiting growth opportunities.

- High Current Liabilities: High current liabilities relative to current assets suggest potential liquidity problems and increased financial risk. The company may struggle to meet its short-term obligations.

- Low Current Liabilities: While generally positive, excessively low current liabilities may indicate underutilization of trade credit, potentially missing opportunities for cost savings.

- High Long-Term Liabilities: High levels of long-term debt increase financial risk and may limit future borrowing capacity. It can also significantly impact profitability due to interest expenses.

- Low Long-Term Liabilities: Low long-term debt might indicate a conservative financial strategy, but it could also limit the company’s ability to finance growth through debt financing.

Analyzing the Income Statement

The income statement, also known as the profit and loss (P&L) statement, provides a snapshot of a company’s financial performance over a specific period. Understanding its components and analyzing trends within them is crucial for assessing a company’s profitability and overall financial health. This analysis allows investors and stakeholders to evaluate the effectiveness of a company’s operations and make informed decisions.

Analyzing the income statement involves examining its key components and their interrelationships to understand how revenue translates into net income. This involves assessing revenue growth, cost control, and the overall efficiency of the company’s operations. By tracking these metrics over time, investors can identify trends and potential areas of concern or opportunity.

Income Statement Components and Profitability

The income statement presents a company’s revenues, expenses, and resulting profits or losses. Key components include revenue, cost of goods sold (COGS), gross profit, operating expenses, operating income, other income and expenses, and net income. Each component significantly impacts profitability. For example, increasing revenue while maintaining or reducing costs directly boosts profitability. Conversely, rising COGS or operating expenses can negatively impact profit margins. A thorough analysis considers the interplay of these elements to provide a comprehensive understanding of profitability drivers.

Analyzing Revenue, COGS, and Operating Expenses Over Time

Trend analysis of revenue, COGS, and operating expenses over multiple periods (e.g., several years or quarters) reveals important insights into a company’s performance. A consistent increase in revenue suggests strong sales growth, while a declining trend may indicate weakening market demand or internal issues. Analyzing COGS trends helps assess the efficiency of production or procurement. Rising COGS without a corresponding increase in revenue suggests increasing input costs or inefficiencies. Similarly, monitoring operating expenses helps identify areas where cost control measures might be needed. Analyzing these trends in conjunction provides a holistic view of a company’s operational efficiency and its ability to generate profits. For instance, a company might experience revenue growth but simultaneously see a disproportionate increase in operating expenses, resulting in stagnant or declining profit margins. This would highlight a need for improved cost management.

Key Income Statement Elements

The following table organizes key income statement elements, highlighting their relationships:

| Revenue | Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) | Gross Profit | Operating Expenses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sales revenue from products or services | Direct costs associated with producing goods or services (e.g., raw materials, direct labor) | Revenue – COGS (Indicates profitability before operating expenses) | Expenses incurred in running the business (e.g., salaries, rent, marketing) |

| Operating Income (Gross Profit – Operating Expenses) | |||

| Other Income/Expenses (e.g., interest income, investment losses) | |||

| Net Income (Operating Income + Other Income/Expenses – Taxes) |

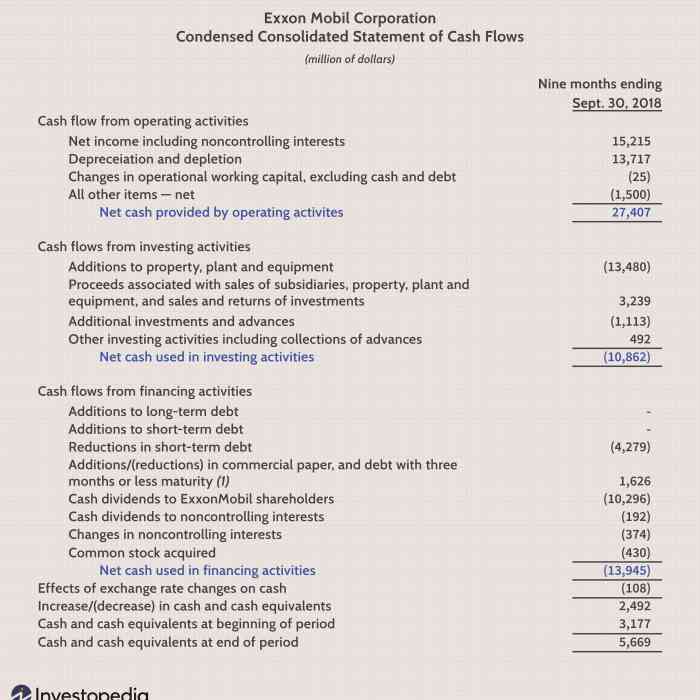

Analyzing the Cash Flow Statement

The cash flow statement provides a crucial perspective on a company’s financial health, complementing the information presented in the balance sheet and income statement. Unlike the accrual-based income statement, the cash flow statement focuses solely on the actual cash inflows and outflows during a specific period. Analyzing this statement allows investors and analysts to assess a company’s liquidity, solvency, and overall financial flexibility.

The cash flow statement is divided into three main sections, each offering valuable insights into different aspects of a company’s operations. Understanding these sections and their interrelationships is vital for a complete financial analysis.

Cash Flow from Operating Activities

This section reflects the cash generated or consumed by a company’s core business operations. It shows the net cash effect of transactions that enter into the determination of net income. Positive cash flow from operations indicates a healthy and profitable business model capable of generating cash from its day-to-day activities. Conversely, negative cash flow from operations can signal underlying problems, potentially requiring closer scrutiny. Methods for calculating this cash flow include the direct method and the indirect method, with the indirect method being more commonly used. Analyzing this section involves examining individual line items to understand the drivers of cash inflows and outflows. For example, a significant increase in accounts receivable might suggest slow collections, impacting cash flow negatively, even if sales are strong. Conversely, a decrease in accounts payable might indicate tighter credit terms, requiring more cash outflows.

Cash Flow from Investing Activities

This section details cash flows related to investments in long-term assets, such as property, plant, and equipment (PP&E), as well as acquisitions and divestitures. A significant outflow in this section typically reflects capital expenditures (CapEx) – investments intended to increase future capacity or efficiency. While CapEx represents a cash outflow, it is crucial for long-term growth and should be considered in the context of a company’s strategic plans. Positive cash flow from investing activities may result from the sale of assets, indicating a strategic shift or potential monetization of non-core businesses. For instance, a large technology company might sell off a less profitable division to reinvest in more promising areas. Analyzing this section helps assess a company’s investment strategy and its impact on future growth.

Cash Flow from Financing Activities

This section focuses on cash flows related to a company’s financing structure. This includes transactions related to debt, equity, and dividends. Cash inflows might arise from issuing debt or equity, while outflows might be due to debt repayments, dividend payments, or share repurchases. Analyzing this section reveals a company’s approach to financing its operations and its capital structure. For example, consistently high levels of debt financing might signal financial risk, whereas a strong reliance on equity financing could suggest a more conservative approach. A company consistently repurchasing its own shares might indicate confidence in its future prospects and a belief that the shares are undervalued.

Free Cash Flow and its Significance

Free cash flow (FCF) represents the cash flow available to the company after accounting for capital expenditures necessary to maintain or grow the business. It’s calculated as:

Free Cash Flow = Cash Flow from Operations – Capital Expenditures

. FCF is a critical metric because it reflects the cash available for distribution to shareholders (through dividends or share repurchases), debt repayment, or reinvestment in other growth opportunities. A consistently high FCF indicates strong financial health and a company’s ability to fund its operations and future growth without relying heavily on external financing. Conversely, negative or consistently low FCF can raise concerns about a company’s long-term viability and its ability to meet its obligations. For example, a company with negative FCF might need to issue additional debt or equity to fund its operations, increasing its financial risk.

Common-Size Statements and Trend Analysis

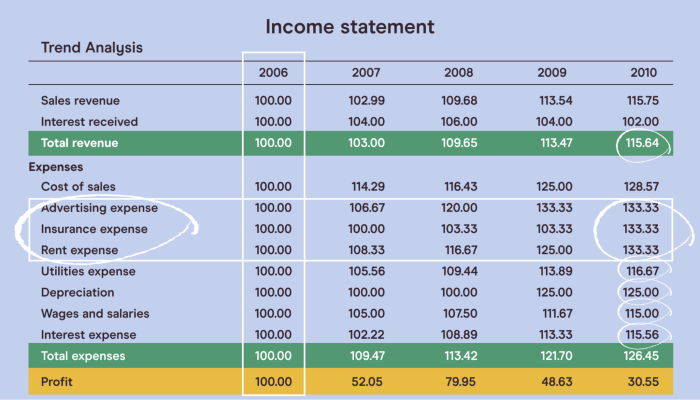

Common-size statements and trend analysis are powerful tools for enhancing the understanding of a company’s financial performance and position over time. They provide a standardized framework for comparing financial data across different periods, regardless of the absolute size of the company, and allow for easier identification of significant changes and trends. This facilitates more insightful analysis than simply looking at raw numbers.

By expressing financial statement items as percentages of a base figure, common-size statements allow for meaningful comparisons between companies of different sizes and across different time periods. Trend analysis, on the other hand, focuses on tracking changes in key financial metrics over several periods, revealing patterns and potential issues that might not be immediately apparent from a single year’s data. Together, these techniques provide a robust analytical approach.

Creating Common-Size Balance Sheets and Income Statements

Common-size financial statements present each line item as a percentage of a base figure. For the balance sheet, total assets are the base; for the income statement, net sales (or revenue) is typically used. This standardization allows for easier comparison of financial structure and performance across different companies or time periods. To create a common-size balance sheet, each asset, liability, and equity account is divided by total assets and multiplied by 100 to express it as a percentage. Similarly, for a common-size income statement, each revenue and expense item is divided by net sales and multiplied by 100.

For example, if a company has total assets of $1,000,000 and cash of $100,000, the common-size balance sheet would show cash as 10% of total assets ($100,000 / $1,000,000 * 100%). If the same company has net sales of $2,000,000 and cost of goods sold of $1,000,000, the common-size income statement would show the cost of goods sold as 50% of net sales ($1,000,000 / $2,000,000 * 100%). This process is repeated for all line items on both statements.

Comparing Common-Size Statements and Absolute Values

Common-size statements offer several advantages over analyzing absolute values alone. Analyzing absolute values can be misleading when comparing companies of different sizes. A company with $10 million in revenue might seem significantly larger than one with $1 million in revenue, but a common-size analysis might reveal similar profit margins, indicating comparable profitability despite the difference in scale. Common-size statements also facilitate trend analysis by providing a consistent basis for comparison over time, even if the overall size of the company’s operations has changed substantially. Absolute values, however, are still necessary to understand the overall scale of the business and the monetary amounts involved in various aspects of its operations. Therefore, both absolute and common-size data provide a more complete picture.

Conducting Trend Analysis Using Financial Statement Data

Trend analysis involves calculating the percentage change in key financial statement items over several periods. This helps identify trends and patterns in a company’s performance. The process involves selecting key metrics – such as revenue, net income, assets, liabilities, and key ratios – and then calculating the percentage change from one period to the next. For example, if revenue was $1 million in Year 1 and $1.2 million in Year 2, the percentage change is calculated as (($1.2 million – $1 million) / $1 million) * 100% = 20%. This calculation is repeated for each subsequent period, allowing for the identification of upward or downward trends. A company experiencing consistent revenue growth, for instance, would show a positive percentage change over multiple years. Conversely, a declining trend would be indicated by negative percentage changes. Analyzing these trends provides valuable insights into the company’s long-term growth prospects and potential challenges.

Financial Statement Fraud Detection

Detecting financial statement fraud requires a keen eye for inconsistencies and a thorough understanding of accounting principles. While complete prevention is impossible, diligent analysis can significantly reduce the risk of undetected manipulation. This section will Artikel key red flags and techniques for identifying potential fraudulent activity.

Identifying potential red flags and warning signs requires a multi-faceted approach, combining analytical skills with a healthy dose of skepticism. Several warning signs can individually appear innocuous, but their combined presence often suggests deeper issues.

Red Flags and Warning Signs of Financial Statement Manipulation

Several indicators can signal potential financial statement manipulation. These range from unusual accounting practices to discrepancies between reported performance and operational realities. Careful examination of these areas is crucial.

- Unusual or Unexplained Transactions: A sudden surge in unusual or complex transactions, particularly those lacking clear business rationale, can be a warning sign. For example, a company suddenly engaging in numerous related-party transactions without clear justification merits scrutiny.

- Aggressive Accounting Practices: Companies employing aggressive accounting methods, such as overly optimistic revenue recognition or overly conservative expense recognition, may be attempting to inflate profits. This might include premature revenue recognition before a transaction is complete or delaying the recognition of expenses to improve short-term results.

- Discrepancies Between Financial Statements and Operational Performance: Significant inconsistencies between reported financial results and observable operational realities, such as declining sales despite reported profit growth, are cause for concern. For instance, a company reporting high profitability while simultaneously experiencing significant customer churn or supply chain disruptions should be investigated.

- Lack of Transparency and Internal Controls: A lack of transparency in financial reporting, coupled with weak internal controls, provides fertile ground for fraudulent activity. This includes a lack of independent audit oversight or a failure to document financial transactions properly.

- Changes in Accounting Methods Without Justification: Significant shifts in accounting methods without a clear, justifiable reason, especially if they result in a material improvement in reported financial performance, should be treated with caution. This could involve a switch to a less conservative accounting method without a proper explanation.

The Importance of Benchmarking and Peer Comparisons

Comparing a company’s financial statements to industry benchmarks and peer companies is crucial for fraud detection. This comparative analysis helps establish reasonable expectations for performance and highlights any significant deviations that warrant further investigation. Benchmarking provides context and helps determine whether reported figures align with industry norms.

For example, if a company’s profit margin is significantly higher than its competitors’ margins without a clear explanation (e.g., superior efficiency or a unique business model), it might indicate potential accounting irregularities. Similarly, a company consistently outperforming its peers across multiple key metrics should be scrutinized for the possibility of overstated results. Analyzing ratios such as gross profit margin, operating profit margin, and return on assets in comparison to industry averages and peer companies can reveal inconsistencies that might signal fraud.

Examples of Accounting Irregularities and Their Impact

Several well-known cases illustrate the devastating impact of accounting irregularities on financial statement interpretation. These cases highlight the importance of thorough analysis and due diligence.

- Enron: Enron’s infamous use of special purpose entities (SPEs) to hide debt and inflate profits exemplifies how complex accounting structures can be used to mask fraudulent activities. This led to a significant overstatement of assets and earnings, ultimately resulting in the company’s bankruptcy.

- WorldCom: WorldCom’s fraudulent accounting practices, primarily involving the capitalization of operating expenses, artificially inflated its earnings and assets. This misrepresentation misled investors and ultimately led to the company’s collapse.

These examples underscore the importance of understanding the underlying business operations and critically evaluating the reported financial figures. A company’s financial statements should always be viewed in conjunction with other qualitative factors, such as management’s reputation, industry trends, and overall economic conditions.

Using Financial Statements for Forecasting

Financial statements, including the balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement, provide a historical record of a company’s financial performance. However, their true power lies in their ability to inform future projections and forecasts. By analyzing trends and patterns within these statements, businesses can develop informed estimates of future financial performance, aiding in strategic planning, investment decisions, and resource allocation.

Analyzing historical financial data allows businesses to identify growth trends, seasonal variations, and the impact of specific business decisions. This information forms the basis for creating more accurate financial forecasts. Extrapolating past performance, while acknowledging its limitations, is a crucial step in developing realistic financial projections.

Developing a Simple Financial Forecast

A simple financial forecast typically involves projecting key financial statement items for a future period, usually one to three years. This process relies heavily on the analysis of historical data and assumptions about future conditions. A common approach uses the percentage-of-sales method, where key line items are projected as a percentage of anticipated future sales revenue.

The process can be broken down into several steps:

1. Sales Forecast: Begin by projecting future sales revenue. This is often the most crucial step, as it forms the foundation for the remaining projections. Consider factors such as market growth, competitive landscape, and planned marketing initiatives. For example, if a company has experienced consistent 10% annual sales growth over the past three years, a reasonable initial assumption might be continued 10% growth in the next year.

2. Projecting Cost of Goods Sold (COGS): Project COGS as a percentage of projected sales. If the historical COGS-to-sales ratio has been relatively stable, this percentage can be used for the forecast. For example, if the COGS-to-sales ratio has averaged 60% over the past few years, a similar ratio can be applied to the projected sales to estimate future COGS.

3. Projecting Operating Expenses: Project operating expenses similarly, as a percentage of projected sales or based on previous trends. Consider any planned changes in expenses, such as increases in marketing or research and development.

4. Projecting Income Taxes: Estimate income taxes based on the projected net income and the applicable tax rate.

5. Projecting Balance Sheet Items: Project balance sheet items like accounts receivable, inventory, and accounts payable based on historical trends and projected sales. For instance, if the average collection period for accounts receivable has been 45 days, this can be used to estimate the future accounts receivable balance.

6. Projecting Cash Flow: Project cash flows by considering projected revenues, expenses, and changes in working capital. This can be done using the direct or indirect method, mirroring the historical cash flow statement.

Limitations of Using Historical Data for Future Predictions

While historical data is invaluable for forecasting, it’s crucial to acknowledge its limitations. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results. Unforeseen events, such as economic downturns, changes in regulations, or unexpected competition, can significantly impact future performance. Furthermore, simply extrapolating past trends without considering external factors can lead to inaccurate and misleading forecasts. For example, a company that experienced rapid growth in a booming market may not maintain that growth rate if the market matures or faces increased competition. Therefore, any forecast should incorporate qualitative factors and sensitivity analysis to account for uncertainty and potential deviations from historical trends.

Wrap-Up

Mastering financial statement analysis empowers you with a critical lens to assess a company’s financial well-being. By understanding the interplay between the balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement, and by employing techniques like ratio analysis and trend analysis, you can gain invaluable insights into a company’s profitability, liquidity, solvency, and overall financial health. Remember, while financial statements provide a crucial foundation, they should be interpreted within a broader context, considering industry benchmarks and qualitative factors. This comprehensive approach will enable you to make more informed and confident financial decisions.

Expert Answers

What are the main limitations of financial statement analysis?

Financial statements reflect historical data and may not accurately predict future performance. They can be manipulated, and they don’t always capture qualitative factors like management quality or industry trends.

How often should financial statements be analyzed?

The frequency depends on the context. For investment decisions, regular analysis (quarterly or annually) is crucial. For internal management, more frequent monitoring (monthly) might be necessary.

What is the difference between liquidity and solvency ratios?

Liquidity ratios measure a company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations, while solvency ratios assess its ability to meet its long-term obligations.

Where can I find industry benchmarks for financial ratios?

Industry benchmarks are available through financial databases (like Bloomberg or Refinitiv), industry reports, and government publications.