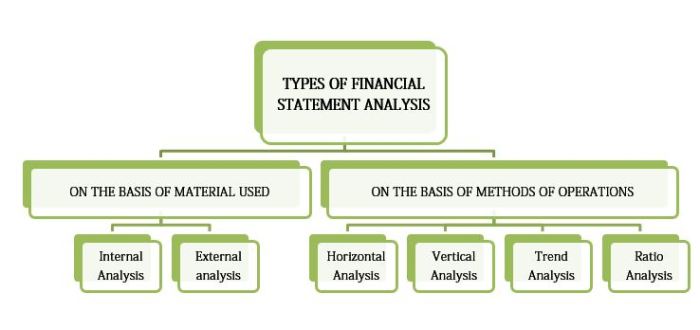

Understanding a company’s financial health requires more than just glancing at the bottom line. Financial Statement Analysis Techniques provide a robust toolkit for deciphering the intricate narrative hidden within financial reports. By employing various methods such as ratio analysis, trend analysis, and cash flow analysis, we gain crucial insights into a company’s liquidity, profitability, solvency, and overall financial performance. This allows for informed decision-making, whether you’re an investor assessing risk, a creditor evaluating creditworthiness, or a manager striving for operational efficiency.

These techniques aren’t just for seasoned financial professionals; they empower anyone seeking a deeper understanding of a company’s financial standing. From interpreting key ratios to visualizing trends over time, mastering these methods unlocks a world of valuable information, enabling better financial literacy and more astute business decisions.

Ratio Analysis

Ratio analysis is a crucial tool in financial statement analysis, providing insights into a company’s performance, financial health, and risk profile. By examining the relationships between different line items in the financial statements, analysts can derive meaningful conclusions about a company’s operational efficiency, liquidity, solvency, and profitability. This analysis allows for comparisons across time periods for the same company and between different companies within the same industry.

Liquidity Ratios

Liquidity ratios assess a company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations as they come due. A healthy liquidity position is essential for a company’s survival and continued operation. Insufficient liquidity can lead to financial distress and even bankruptcy.

Key liquidity ratios include:

- Current Ratio: This ratio measures the ability of a company to pay off its current liabilities (due within one year) with its current assets. It is calculated as:

Current Ratio = Current Assets / Current Liabilities

A higher current ratio generally indicates better liquidity, although an excessively high ratio might suggest inefficient use of assets.

- Quick Ratio (Acid-Test Ratio): This is a more stringent measure of liquidity, excluding inventory from current assets because inventory might not be easily converted to cash. It’s calculated as:

Quick Ratio = (Current Assets – Inventory) / Current Liabilities

A higher quick ratio suggests a stronger ability to meet short-term obligations with readily available assets.

- Cash Ratio: This is the most conservative liquidity measure, considering only the most liquid assets (cash and cash equivalents) against current liabilities. It’s calculated as:

Cash Ratio = (Cash + Cash Equivalents) / Current Liabilities

A higher cash ratio indicates a very strong ability to meet immediate obligations.

Profitability Ratios

Profitability ratios evaluate a firm’s ability to generate earnings from its operations and overall efficiency in utilizing its assets. These ratios are essential for assessing a company’s performance and its capacity to generate returns for its stakeholders. A strong profitability profile attracts investors and indicates operational success.

Examples of profitability ratios and their implications:

- Gross Profit Margin: This ratio shows the profitability of a company’s core operations after deducting the cost of goods sold. A higher gross profit margin indicates greater efficiency in production and pricing. It is calculated as:

Gross Profit Margin = (Revenue – Cost of Goods Sold) / Revenue

- Net Profit Margin: This ratio reflects the overall profitability of a company after considering all expenses, including interest and taxes. A higher net profit margin suggests superior overall operational efficiency and cost control. It is calculated as:

Net Profit Margin = Net Profit / Revenue

- Return on Assets (ROA): This ratio measures how efficiently a company utilizes its assets to generate earnings. A higher ROA indicates better asset management and profitability. It is calculated as:

Return on Assets (ROA) = Net Profit / Total Assets

Comparison of Profitability Ratios

| Ratio | Formula | Focus | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gross Profit Margin | (Revenue – Cost of Goods Sold) / Revenue | Profitability from core operations | Higher is better, indicates efficient production and pricing |

| Net Profit Margin | Net Profit / Revenue | Overall profitability after all expenses | Higher is better, reflects overall efficiency and cost control |

| Return on Assets (ROA) | Net Profit / Total Assets | Efficiency of asset utilization | Higher is better, indicates effective asset management |

| Return on Equity (ROE) | Net Profit / Shareholder’s Equity | Return generated for shareholders | Higher is better, indicates strong returns for investors |

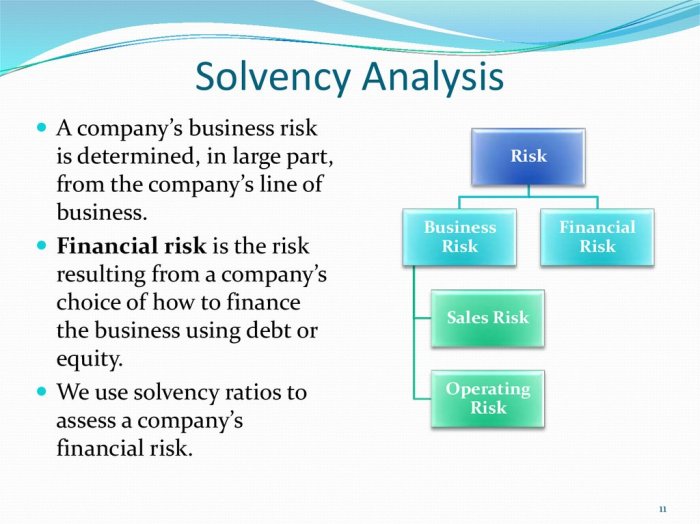

Solvency Ratios

Solvency ratios measure a company’s ability to meet its long-term obligations and its overall financial stability. These ratios provide insights into a company’s financial risk profile and its capacity to withstand financial distress. A strong solvency position is crucial for long-term survival and growth.

- Debt-to-Equity Ratio: This ratio indicates the proportion of a company’s financing that comes from debt relative to equity. A higher ratio suggests higher financial risk. It is calculated as:

Debt-to-Equity Ratio = Total Debt / Total Equity

- Times Interest Earned Ratio: This ratio measures a company’s ability to cover its interest expenses with its earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT). A higher ratio indicates a stronger ability to meet interest obligations. It is calculated as:

Times Interest Earned Ratio = EBIT / Interest Expense

- Debt-to-Asset Ratio: This ratio indicates the proportion of a company’s assets that are financed by debt. A higher ratio signifies greater financial leverage and higher risk. It is calculated as:

Debt-to-Asset Ratio = Total Debt / Total Assets

Trend Analysis

Trend analysis is a crucial financial statement analysis technique that involves examining the historical data of a company’s key financial metrics to identify patterns and predict future performance. By visualizing these trends, we can gain valuable insights into the company’s growth trajectory, profitability, and overall financial health. This analysis goes beyond a single snapshot in time, providing a dynamic perspective on the company’s financial well-being.

Analyzing trends allows for a deeper understanding of a company’s performance compared to simply reviewing individual financial statements. Identifying consistent upward or downward movements in key metrics provides valuable information for decision-making, whether for internal management or external investors. This approach allows for a proactive identification of potential risks and opportunities, enabling informed strategic planning.

Graphical Representation of Financial Trends

Data visualization is essential for effectively communicating the insights derived from trend analysis. Different chart types offer unique advantages in presenting financial data. Line graphs, for instance, are particularly effective for showing changes over time, clearly illustrating the progression of key metrics such as revenue, net income, or debt levels. Bar charts, on the other hand, are useful for comparing the performance of different metrics within a specific time period or across different companies. The choice of chart depends on the specific information being conveyed and the desired level of detail. For example, a line graph would effectively display the year-over-year growth of a company’s sales, while a bar chart would be suitable for comparing the profitability of different product lines within a single year. Choosing the appropriate chart type enhances the clarity and understanding of the trends identified.

Horizontal Analysis of Financial Statements

Horizontal analysis, also known as trend analysis, involves comparing financial statement data over multiple periods to identify percentage changes. This provides a clearer picture of the growth or decline in various financial metrics. The process involves calculating the percentage change for each line item on the financial statement from one period to the next. This is typically done by subtracting the prior period’s value from the current period’s value, and then dividing the result by the prior period’s value. The resulting percentage shows the growth or decline in that specific line item. For example, if a company’s revenue increased from $100,000 in 2022 to $120,000 in 2023, the percentage change would be calculated as (($120,000 – $100,000) / $100,000) * 100% = 20%. This indicates a 20% increase in revenue. Consistent application of this calculation across all line items allows for a comprehensive understanding of the company’s overall financial performance trends. The use of percentage changes provides a standardized measure, facilitating comparisons even when the absolute values are significantly different.

Comparison of Chart Types for Representing Financial Trends

Line graphs are ideal for showcasing continuous trends over time. They effectively illustrate the direction and magnitude of change in financial metrics. However, they can become cluttered with many data series. Bar charts, conversely, are excellent for comparing discrete data points across different categories or time periods. They are easily interpreted, even by those without extensive financial knowledge. However, they may not be as effective in displaying gradual changes over time. A potential weakness of both line and bar charts is the difficulty in accurately representing very small or very large values; logarithmic scales can help address this issue. The best choice ultimately depends on the nature of the data and the message being communicated.

Predicting Future Financial Performance Using Trend Analysis

Trend analysis can be used to forecast future financial performance by extrapolating historical trends. For example, if a company has consistently increased its revenue by 10% annually over the past five years, a simple projection might suggest a similar growth rate in the coming years. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that this is a simplified model and doesn’t account for external factors or changes in the business environment. More sophisticated forecasting techniques, such as regression analysis, can incorporate additional variables to improve predictive accuracy. For instance, a company experiencing consistent revenue growth might be expected to see a similar trend in net income, but only if other factors like cost of goods sold and operating expenses remain relatively stable. A significant change in these factors could disrupt the projected trend. Therefore, while trend analysis can be a valuable tool for prediction, it’s crucial to consider its limitations and use it in conjunction with other forecasting methods. A company like Amazon, known for its rapid growth over many years, could be analyzed using trend analysis to project future sales, but this projection would need to consider potential market saturation, competitive pressures, and economic downturns.

Common-Size Analysis

Common-size analysis is a valuable financial statement analysis technique that simplifies the comparison of companies of different sizes, or the same company across different periods. By expressing each line item as a percentage of a base figure, common-size statements reveal the relative importance of various accounts within the financial structure. This allows for a more insightful understanding of a company’s financial health than simply looking at absolute numbers.

Creating Common-Size Balance Sheets and Income Statements

The process of creating common-size financial statements involves expressing each item on the balance sheet and income statement as a percentage of a base figure. For the balance sheet, total assets are typically used as the base. Each asset, liability, and equity account is then divided by total assets and multiplied by 100 to express it as a percentage. For the income statement, net sales (or revenue) serves as the base. Each revenue and expense item is divided by net sales and multiplied by 100 to express it as a percentage.

For example, consider a simplified balance sheet:

| Account | Amount ($) | Common-Size Percentage |

|———————-|————|————————|

| Cash | 10,000 | 10% |

| Accounts Receivable | 20,000 | 20% |

| Total Assets | 100,000 | 100% |

| Accounts Payable | 15,000 | 15% |

| Equity | 85,000 | 85% |

| Total Liabilities & Equity | 100,000 | 100% |

In this example, Cash (10,000) is 10% of Total Assets (100,000), Accounts Receivable (20,000) is 20% of Total Assets, and so on. A similar process is followed for the income statement, using net sales as the base. This allows for easy comparison across different years or different companies, regardless of their size.

Comparison of Common-Size Analysis and Ratio Analysis

Both common-size analysis and ratio analysis are valuable tools for financial statement analysis, but they offer different perspectives. Ratio analysis focuses on the relationships between different line items on the financial statements, providing insights into profitability, liquidity, solvency, and efficiency. Common-size analysis, on the other hand, focuses on the relative proportions of different line items within a single statement, highlighting the relative importance of each account. They are often used together to provide a more comprehensive understanding of a company’s financial performance. Ratio analysis provides specific insights into financial health through comparisons, while common-size analysis reveals the relative size and importance of different financial components.

Facilitating Inter-Company Comparisons

Common-size analysis is particularly useful for comparing companies of different sizes. Because the data is expressed as percentages, the absolute size of the companies becomes irrelevant. For instance, comparing a small startup with a large multinational corporation using absolute numbers is difficult and often misleading. However, by converting their financial statements into common-size statements, a meaningful comparison of their financial structures and performance can be made. This allows for a more accurate assessment of relative strengths and weaknesses.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Common-Size Analysis

| Advantages | Disadvantages | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Easy to understand and interpret | Does not provide absolute values | Facilitates inter-company comparisons | May not capture all aspects of financial health |

| Highlights the relative importance of different accounts | Can be misleading if used in isolation | Useful for trend analysis over time | Requires careful selection of the base figure |

Cash Flow Analysis

Cash flow analysis is a crucial aspect of financial statement analysis, providing insights into a company’s ability to generate and manage cash. Unlike accrual-based accounting profits, which can be influenced by non-cash items like depreciation, cash flow statements offer a direct measure of a company’s liquidity and solvency. A thorough analysis of cash flows helps investors and creditors understand the true financial health of a business beyond the numbers reported on the income statement and balance sheet.

Key Components of the Statement of Cash Flows and Their Significance

The statement of cash flows categorizes cash inflows and outflows into three primary activities: operating, investing, and financing. Understanding the interplay between these activities is vital for a complete assessment of a company’s financial position. Operating activities represent the cash generated from the core business operations. Investing activities involve the purchase and sale of long-term assets, reflecting strategic decisions on growth and capital expenditures. Financing activities encompass how the company raises and utilizes capital, including debt and equity. A healthy company typically shows positive operating cash flow, strategically managed investing cash flows, and appropriately financed growth.

Analyzing Cash Flow from Operating, Investing, and Financing Activities Separately

Analyzing each cash flow activity separately reveals important aspects of a company’s financial strategy and performance. Positive operating cash flow indicates strong profitability and efficient management of working capital. Analyzing investing activities helps determine whether a company is investing in growth opportunities or divesting assets. Examination of financing activities shows how the company funds its operations and growth, providing insight into its capital structure and reliance on debt or equity. Significant discrepancies or trends in any of these areas can signal potential financial issues. For example, consistently negative operating cash flow despite positive net income could indicate aggressive accounting practices or unsustainable business models.

Cash Flow Analysis and Discrepancies Between Reported Profits and Actual Cash Generation

Cash flow analysis can highlight discrepancies between a company’s reported net income and its actual cash generation. This is because net income is calculated using accrual accounting, which includes non-cash items like depreciation and amortization. Cash flow, on the other hand, focuses solely on actual cash receipts and payments. A company might report high profits but have low or negative cash flow if it has high accounts receivable, significant capital expenditures, or other non-cash expenses. This discrepancy can be a critical warning sign, indicating potential problems with revenue recognition, inventory management, or overall financial health. For instance, a company with high sales growth but low cash flow from operations might be struggling to collect payments from customers.

Assessing a Company’s Ability to Meet Short-Term and Long-Term Obligations Using Cash Flow Analysis

Cash flow analysis is essential for assessing a company’s ability to meet its short-term and long-term obligations. Short-term obligations, such as accounts payable and salaries, are typically met using cash generated from operating activities. A strong positive operating cash flow is a positive indicator of a company’s ability to meet its short-term debts. Long-term obligations, such as debt repayments and capital expenditures, require careful planning and management of cash flows from all three activities. Analyzing the free cash flow (operating cash flow minus capital expenditures) provides a clear picture of the company’s ability to repay debt, invest in growth, and distribute dividends. A company with consistently negative free cash flow may struggle to meet its long-term financial obligations. For example, a company with a high debt burden and low free cash flow might face difficulties in servicing its debt, leading to potential financial distress.

Vertical Analysis

Vertical analysis, also known as common-size analysis, is a powerful financial statement analysis technique that expresses each line item in a financial statement as a percentage of a base figure. This allows for a more meaningful comparison of financial data across different periods, companies of varying sizes, or even different industries. By normalizing the data, vertical analysis reveals the relative importance of each account and highlights significant changes in the composition of a company’s assets, liabilities, and equity.

Methodology of Vertical Analysis

Vertical analysis involves calculating the percentage of each line item relative to a base figure. For the balance sheet, the base figure is usually total assets. Each asset, liability, and equity account is then expressed as a percentage of total assets. For the income statement, the base figure is typically net sales or revenue. Each expense and profit item is then expressed as a percentage of net sales. The calculation is straightforward: (Line Item / Base Figure) * 100%.

Examples of Vertical Analysis Applications

Imagine comparing two companies, Company A and Company B, both in the retail industry but with vastly different asset sizes. While a simple comparison of their raw financial figures might be misleading, vertical analysis provides a clearer picture. For instance, if Company A has a cost of goods sold representing 60% of net sales, while Company B’s cost of goods sold represents 70%, vertical analysis reveals that Company B has a higher proportion of its revenue dedicated to the cost of goods sold, suggesting potential areas for improvement in efficiency or pricing strategy. Similarly, a high percentage of accounts receivable relative to total assets might indicate potential problems with credit collection policies. Analyzing changes in these percentages over time can reveal trends in a company’s operational efficiency and financial health.

Comparison of Vertical and Horizontal Analysis

Both vertical and horizontal analysis are valuable tools for financial statement analysis, but they offer different perspectives. Vertical analysis focuses on the internal composition of a financial statement at a single point in time, showing the relationship between different accounts within the statement. Horizontal analysis, on the other hand, examines changes in the financial statement items over time, revealing trends and growth patterns. While vertical analysis normalizes the data for size, horizontal analysis normalizes the data for time. They are complementary techniques; using both provides a more comprehensive understanding of a company’s financial performance and position.

Step-by-Step Guide to Conducting Vertical Analysis

Performing vertical analysis is a systematic process. Here’s a step-by-step guide for both the balance sheet and income statement:

- Balance Sheet Vertical Analysis:

- Determine the base figure: Total Assets.

- For each asset, liability, and equity account, divide the account balance by the total assets.

- Multiply the result by 100 to express the result as a percentage.

- Repeat steps 2 and 3 for all accounts.

- Analyze the resulting percentages to identify significant changes in the composition of assets, liabilities, and equity over time.

- Income Statement Vertical Analysis:

- Determine the base figure: Net Sales (Revenue).

- For each revenue and expense item, divide the account balance by net sales.

- Multiply the result by 100 to express the result as a percentage.

- Repeat steps 2 and 3 for all accounts.

- Analyze the resulting percentages to identify significant changes in the composition of revenues and expenses over time. For example, a consistently increasing percentage of cost of goods sold could indicate a problem with efficiency or pricing.

Ending Remarks

In conclusion, mastering Financial Statement Analysis Techniques is paramount for anyone navigating the complex world of finance. Whether it’s evaluating a potential investment, understanding a company’s operational efficiency, or assessing its long-term sustainability, the methodologies explored provide a comprehensive framework for interpreting financial data. By combining different analytical approaches, a clearer picture emerges, revealing opportunities and risks that might otherwise remain hidden. The ability to effectively analyze financial statements is not merely a skill; it’s a key to informed decision-making and success in the business world.

Helpful Answers

What is the difference between horizontal and vertical analysis?

Horizontal analysis compares financial data over time (e.g., year-over-year changes), while vertical analysis compares items within a single financial statement as percentages of a base figure (e.g., each asset as a percentage of total assets).

How can I improve the accuracy of my financial statement analysis?

Accuracy hinges on using reliable, audited financial statements, comparing companies within the same industry, and understanding the limitations of each analytical technique. Consider consulting with a financial professional for complex analyses.

What are some limitations of financial statement analysis?

Financial statements reflect historical data, not future performance. They can be manipulated, and the analysis relies on the accuracy of the underlying data. Furthermore, qualitative factors (management quality, competitive landscape) are not directly captured.