Investment Portfolio Optimization is the art and science of crafting an investment strategy tailored to an individual’s unique financial goals and risk tolerance. It’s more than just picking stocks; it’s about strategically allocating assets across various investment vehicles to maximize returns while minimizing risk. This involves a deep understanding of market dynamics, risk management techniques, and the application of sophisticated mathematical models to achieve optimal portfolio construction and performance.

This exploration delves into the core principles of portfolio optimization, examining diverse approaches, risk mitigation strategies, and the practical application of these strategies in real-world scenarios. We’ll navigate the complexities of asset allocation, the influence of market factors, and the importance of understanding one’s own investor profile to create a resilient and profitable portfolio.

Defining Investment Portfolio Optimization

Investment portfolio optimization is the process of constructing a portfolio of assets that maximizes expected returns for a given level of risk, or minimizes risk for a given level of expected return. It’s a systematic approach to building a portfolio that aligns with an investor’s specific financial goals and risk tolerance. This involves careful consideration of various factors, including asset allocation, diversification, and risk management.

Core Principles of Investment Portfolio Optimization hinge on the understanding that investors are risk-averse, seeking the highest possible return for a given level of risk. The process involves identifying the optimal mix of assets – stocks, bonds, real estate, etc. – to achieve this balance. This is usually achieved through mathematical models and algorithms that analyze historical data and market trends to predict future performance. Diversification, a key principle, aims to reduce overall portfolio risk by spreading investments across different asset classes that are not perfectly correlated.

Investor Objectives Achieved Through Optimization vary widely depending on individual circumstances and goals. Some investors prioritize capital preservation and minimizing risk, while others are willing to accept higher risk for potentially higher returns. Optimization techniques help investors tailor their portfolios to achieve specific objectives, such as retirement planning, wealth accumulation, or funding a child’s education. The process allows for a data-driven approach to investment decisions, reducing reliance on gut feelings or market sentiment.

Investor Profiles and Optimization Needs: Different investors have vastly different needs. For example, a young investor with a long time horizon might be comfortable with a portfolio heavily weighted towards equities, aiming for high growth. Conversely, an investor nearing retirement might prefer a more conservative portfolio with a higher allocation to fixed-income securities, prioritizing capital preservation and income generation. A high-net-worth individual might seek sophisticated optimization strategies involving alternative investments and tax optimization, while a risk-averse individual might focus on minimizing volatility and maximizing stability.

Portfolio Optimization Approaches

The following table compares different portfolio optimization approaches, highlighting their key characteristics:

| Asset Class | Risk Tolerance | Return Objective | Optimization Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stocks, Bonds, Real Estate | Moderate | Long-term growth with moderate risk | Mean-Variance Optimization |

| Mostly Bonds, Some Stocks | Low | Capital preservation and income | Risk Parity |

| Stocks, Bonds, Alternative Investments | High | High growth potential | Black-Litterman Model |

| Diversified across multiple asset classes | Customizable | Defined by investor goals | Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) |

Risk Management in Portfolio Optimization

Effective portfolio optimization necessitates a robust risk management framework. Understanding and mitigating risk is crucial for achieving investment goals while protecting capital. This involves carefully considering an investor’s risk tolerance and employing appropriate risk measures and diversification strategies.

Risk Tolerance in Portfolio Construction

An investor’s risk tolerance significantly influences portfolio construction. Risk tolerance represents an individual’s capacity and willingness to accept potential losses in pursuit of higher returns. A conservative investor with low risk tolerance will prefer a portfolio heavily weighted towards low-risk assets like government bonds, while a more aggressive investor with a high risk tolerance might allocate a larger portion to equities and potentially higher-risk alternatives. Understanding this crucial aspect allows for the creation of a portfolio aligned with the investor’s individual financial goals and comfort level. A thorough assessment of risk tolerance, often involving questionnaires and discussions with financial advisors, is paramount before making any significant investment decisions.

Risk Measures

Several quantitative measures exist to assess portfolio risk. Standard deviation, Value at Risk (VaR), and Conditional Value at Risk (CVaR) are commonly used. Standard deviation measures the dispersion of returns around the average, providing a gauge of volatility. A higher standard deviation indicates greater risk. Value at Risk (VaR) quantifies the potential loss in value over a specific time horizon with a given confidence level. For example, a VaR of $10,000 at a 95% confidence level means there is a 5% chance of losing at least $10,000 over the specified period. Conditional Value at Risk (CVaR), also known as Expected Shortfall (ES), measures the expected loss given that the loss exceeds the VaR threshold. CVaR provides a more comprehensive view of tail risk compared to VaR. These metrics offer different perspectives on risk, providing a more holistic understanding of potential losses.

Strategies for Managing and Mitigating Portfolio Risk

Several strategies can be employed to manage and mitigate portfolio risk. Diversification, the cornerstone of risk management, involves spreading investments across different asset classes (e.g., equities, bonds, real estate) and sectors to reduce the impact of any single asset’s poor performance. Hedging involves using financial instruments, such as options or futures contracts, to offset potential losses from adverse price movements. Regular portfolio rebalancing, adjusting asset allocations to maintain the desired risk profile, is another crucial strategy. Furthermore, setting stop-loss orders can limit potential losses by automatically selling an asset when it reaches a predetermined price. Stress testing, simulating the portfolio’s performance under various adverse market conditions, helps identify vulnerabilities and potential areas for improvement.

Hypothetical Diversified Portfolio

Consider a hypothetical portfolio designed for a moderately risk-tolerant investor aiming for long-term growth. The portfolio allocates 50% to equities, 30% to bonds, and 20% to real estate. The equity portion is further diversified across different sectors, including technology (20%), healthcare (15%), consumer staples (10%), and financials (5%). This diversification reduces the impact of underperformance in any single sector. The bond allocation consists primarily of investment-grade corporate bonds and government bonds, providing stability and income. The real estate allocation involves investment in REITs (Real Estate Investment Trusts) for diversification and potential income generation. This asset allocation reflects a balance between growth potential and risk mitigation, suitable for an investor with a moderate risk tolerance. The justification for these asset choices is based on their historical performance, risk profiles, and correlation characteristics. The low correlation between asset classes helps reduce overall portfolio volatility.

Asset Allocation Strategies

Asset allocation is the cornerstone of successful investment portfolio optimization. It involves determining the proportion of your portfolio invested in different asset classes, such as stocks, bonds, real estate, and cash. The strategic choices made here significantly impact both risk and potential returns over the long term. Different approaches exist, each with its own advantages and disadvantages, and the optimal strategy depends heavily on individual circumstances.

Strategic asset allocation and tactical asset allocation are two primary approaches. Strategic asset allocation focuses on a long-term, stable allocation based on an investor’s risk tolerance and long-term financial goals. Tactical asset allocation, conversely, involves actively adjusting the portfolio’s asset mix in response to short-term market fluctuations and anticipated changes in market conditions. The choice between these strategies reflects a fundamental difference in investment philosophy – a passive, long-term perspective versus an active, short-term approach.

Strategic Asset Allocation

Strategic asset allocation involves setting target allocations for different asset classes based on the investor’s risk profile and time horizon. This allocation is typically reviewed and adjusted periodically, but not in response to daily market movements. For instance, a young investor with a long time horizon might adopt a portfolio heavily weighted towards equities, accepting higher risk for potentially greater long-term returns. Conversely, an investor nearing retirement might favor a more conservative approach with a larger allocation to bonds to minimize risk. The core principle is to maintain a consistent allocation over the long run, allowing the portfolio to benefit from market cycles.

Tactical Asset Allocation

Tactical asset allocation involves actively adjusting the portfolio’s asset mix based on market forecasts and perceived opportunities. This approach attempts to capitalize on short-term market trends and outperform the market by shifting allocations towards asset classes expected to perform better. For example, if a tactical asset allocator anticipates a rise in inflation, they might increase the allocation to commodities or inflation-protected securities. Conversely, during a period of expected economic slowdown, they might reduce equity exposure and increase the allocation to safer assets like government bonds. This strategy requires significant market expertise and timing skills, and is often associated with higher transaction costs.

Factors Influencing Asset Allocation Decisions

Several key factors influence asset allocation decisions. Market conditions, including interest rates, inflation, and economic growth forecasts, play a significant role. Investor goals, such as retirement planning, education funding, or wealth preservation, also determine the appropriate level of risk and return. Finally, the investor’s time horizon significantly impacts asset allocation choices. Longer time horizons allow for greater risk-taking, while shorter time horizons often necessitate a more conservative approach. A thorough understanding of these factors is essential for creating a well-diversified and appropriate portfolio.

Portfolio Rebalancing

Rebalancing a portfolio involves adjusting the asset allocation back to its target weights after market fluctuations have caused deviations. This disciplined approach helps maintain the desired risk level and prevent emotional decision-making. For example, if a portfolio initially allocated 60% to equities and 40% to bonds sees equities outperform, the equity portion might rise to 70%. Rebalancing would involve selling some equities and buying bonds to restore the 60/40 allocation. This process helps to lock in profits from outperforming assets and reinvest into underperforming assets, potentially benefiting from their future recovery. Regular rebalancing, typically annually or semi-annually, is crucial for maintaining a well-balanced and risk-managed portfolio.

Adjusting Asset Allocation Based on Market Volatility

Market volatility presents both challenges and opportunities for adjusting asset allocation. During periods of high volatility, investors may choose to reduce their equity exposure and increase their allocation to less volatile assets such as bonds or cash. This is often referred to as a “risk-off” strategy. Conversely, when volatility subsides and market sentiment improves, investors may gradually increase their equity exposure, taking advantage of potentially lower valuations. For instance, during the 2008 financial crisis, many investors shifted significantly towards bonds and cash to protect their capital. As markets recovered, they gradually increased their equity allocations. The key is to maintain a disciplined approach, avoiding impulsive decisions based on short-term market fluctuations. This requires a robust understanding of one’s risk tolerance and long-term investment goals.

Portfolio Optimization Techniques

Portfolio optimization aims to construct an investment portfolio that maximizes returns for a given level of risk or minimizes risk for a given level of return. Several techniques exist to achieve this goal, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. Understanding these techniques is crucial for effective portfolio management.

Mean-Variance Optimization

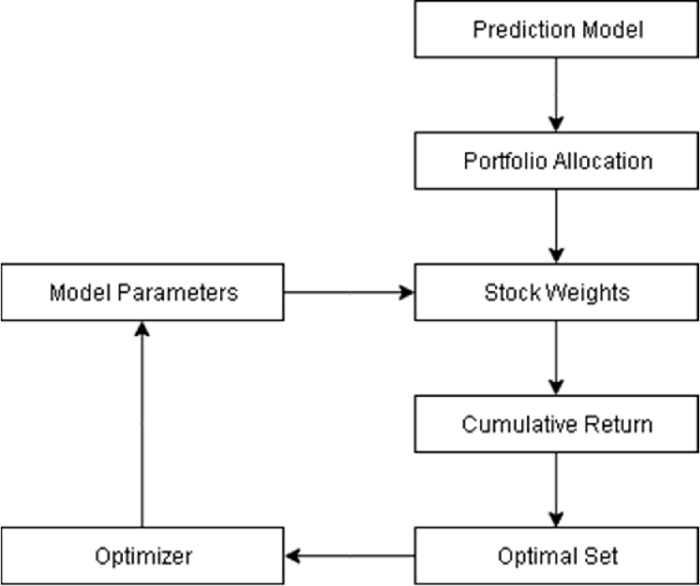

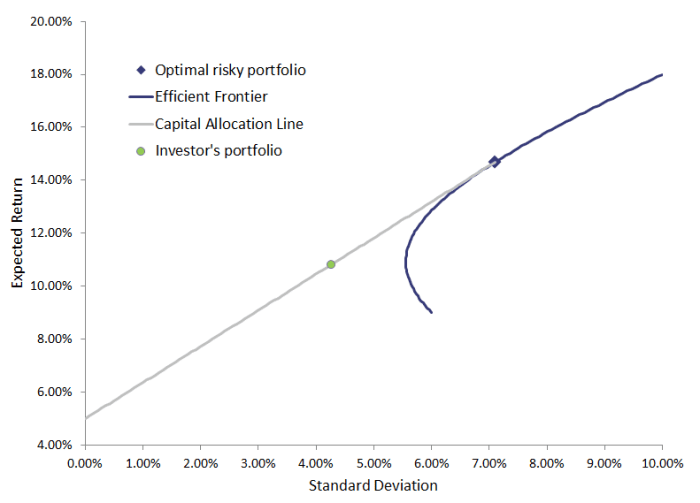

Mean-variance optimization (MVO), pioneered by Harry Markowitz, is a cornerstone of modern portfolio theory. It seeks to find the optimal portfolio allocation by considering the expected return and variance (a measure of risk) of each asset, as well as the covariance between them. The process involves constructing an efficient frontier, which represents the set of portfolios offering the highest expected return for each level of risk.

The process begins with estimating the expected return and covariance matrix of the assets in the portfolio. This typically involves using historical data. For instance, we can calculate the average monthly return for each asset over the past five years to estimate the expected return. The covariance matrix quantifies the relationships between the assets’ returns. A high positive covariance indicates that the assets tend to move together, while a negative covariance suggests they move in opposite directions. These estimates are then used in optimization software or algorithms to calculate the optimal portfolio weights that maximize the Sharpe ratio (a measure of risk-adjusted return).

The Sharpe Ratio is calculated as: (Rp – Rf) / σp, where Rp is the portfolio return, Rf is the risk-free rate, and σp is the portfolio standard deviation.

Limitations of Mean-Variance Optimization

While powerful, mean-variance optimization has limitations. It relies heavily on accurate estimates of expected returns and covariances, which are inherently uncertain. Historical data may not be a reliable predictor of future performance, particularly during periods of significant market shifts. Furthermore, MVO assumes that returns are normally distributed, an assumption often violated in real-world markets. The model can also be sensitive to input data errors and may produce portfolios with extreme allocations (overweighting certain assets).

Comparison of Mean-Variance Optimization with Other Quantitative Techniques

Several alternative techniques address the limitations of mean-variance optimization. Let’s compare MVO with the Black-Litterman model and factor models.

The following table summarizes the advantages and disadvantages:

| Technique | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Mean-Variance Optimization |

|

|

| Black-Litterman Model |

|

|

| Factor Models |

|

|

Practical Applications and Case Studies

Portfolio optimization isn’t just a theoretical concept; it’s a powerful tool used daily by individuals and institutions to manage and grow their investments. Understanding its practical applications and reviewing successful case studies can illuminate its effectiveness and highlight the steps involved in successful implementation. This section will explore real-world examples, detail the implementation process, and present a hypothetical case study to illustrate the optimization process.

Successful portfolio optimization hinges on a deep understanding of the investor’s unique circumstances and goals. A well-defined strategy, meticulously executed, can significantly enhance investment returns while mitigating risks. Conversely, a poorly designed or implemented strategy can lead to suboptimal performance and potentially significant losses.

Real-World Examples of Successful Portfolio Optimization Strategies

Several institutional investors have demonstrated the power of portfolio optimization. Large pension funds, for instance, routinely employ sophisticated optimization models to manage their vast assets, aiming to maximize returns while adhering to strict risk parameters and liability obligations. These models often incorporate complex factors, including inflation forecasts, interest rate projections, and various market scenarios. Similarly, many endowment funds use portfolio optimization techniques to balance their investment objectives with long-term sustainability goals. The success of these strategies often involves a combination of advanced quantitative methods and a deep understanding of macroeconomic trends. For example, a university endowment might use a mean-variance optimization model to balance its holdings across various asset classes (stocks, bonds, real estate, etc.) to achieve a target return while managing the risk of endowment depletion.

Steps Involved in Implementing a Portfolio Optimization Plan

Implementing a portfolio optimization plan involves a structured, multi-step process. First, a thorough understanding of the investor’s risk tolerance, investment goals (e.g., retirement, education), and time horizon is crucial. Next, a suitable asset allocation strategy needs to be defined, based on the investor’s profile and market conditions. This involves selecting the appropriate mix of asset classes, such as stocks, bonds, real estate, and alternative investments. Then, specific investment vehicles within each asset class must be chosen. This selection should consider factors like expense ratios, tax implications, and historical performance. The portfolio is then constructed and regularly monitored and rebalanced to maintain the desired asset allocation and risk profile. Finally, performance is tracked against benchmarks and the strategy is adjusted as needed to reflect changes in market conditions or the investor’s circumstances.

Hypothetical Case Study: A Conservative Investor

Consider a 55-year-old investor, Sarah, with a moderate risk tolerance and a 10-year investment horizon before retirement. Her goal is to preserve capital and generate sufficient income to supplement her retirement savings. Sarah’s portfolio optimization would prioritize capital preservation and income generation. A suitable asset allocation might include 60% bonds (providing stable income and lower volatility), 30% large-cap stocks (for moderate growth potential), and 10% in real estate investment trusts (REITs) for diversification and potential income streams. The bond portion might be invested in a mix of government and high-quality corporate bonds, while the stock portion could be allocated to a diversified index fund. Regular rebalancing would ensure the portfolio remains aligned with her risk tolerance and investment goals throughout the 10-year period.

Portfolio Optimized for Growth: A Descriptive Illustration

A portfolio designed for aggressive growth would prioritize higher-return assets with a corresponding increase in risk. This might include a significant allocation to small-cap stocks (offering higher growth potential but increased volatility), emerging market equities (potential for substantial returns but higher risk), and potentially alternative investments like venture capital or private equity (high risk, high reward). A sample allocation could be 70% equities (split between small-cap, large-cap, and emerging markets), 20% alternative investments, and 10% in bonds (primarily for diversification and risk mitigation). The rationale behind this allocation is the investor’s higher risk tolerance and longer time horizon, allowing them to weather potential market downturns and potentially benefit from significant long-term growth. This aggressive approach requires a deep understanding of market cycles and the ability to tolerate significant short-term fluctuations.

Factors Influencing Portfolio Performance

Portfolio performance is a complex interplay of various factors, both internal and external to the investment strategy itself. Understanding these influences is crucial for effective portfolio management and achieving desired investment goals. While optimization techniques aim to maximize returns for a given level of risk, the actual performance can deviate significantly due to unforeseen market shifts and investor behavior.

Market Factors Impacting Portfolio Performance

Macroeconomic conditions significantly shape investment outcomes. Interest rate changes, for instance, directly affect bond prices; rising rates generally lead to falling bond prices, impacting fixed-income portfolios. Inflation erodes purchasing power, reducing the real return of investments. Strong economic growth typically fuels higher corporate earnings and stock prices, benefiting equity portfolios, while recessions often lead to market declines. Unexpected geopolitical events, such as wars or trade disputes, can also cause significant market volatility and impact portfolio performance unpredictably. For example, the 2008 financial crisis, triggered by the collapse of the US housing market, led to a sharp decline in global stock markets, significantly impacting many investment portfolios regardless of their diversification strategies. Similarly, the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 caused unprecedented market volatility, with sharp initial declines followed by a rapid recovery in certain sectors.

Investor Behavior and Investment Outcomes

Investor psychology plays a surprisingly significant role in portfolio performance. Emotional biases, such as fear and greed, can lead to poor investment decisions. For example, panic selling during market downturns can lock in losses, while chasing high-performing assets during market bubbles can lead to substantial losses when the bubble bursts. Market timing, the attempt to buy low and sell high, is notoriously difficult to execute successfully. Most investors struggle to consistently outperform the market through market timing due to the inherent difficulty in predicting market fluctuations accurately. Behavioral finance research extensively documents the negative impact of emotional decision-making on investment success. A classic example is the “disposition effect,” where investors tend to sell winning investments too early and hold onto losing investments for too long.

Sources of Tracking Error in Portfolio Management

Tracking error measures the difference between a portfolio’s return and the return of its benchmark index. Several factors contribute to tracking error. Transaction costs, such as brokerage fees and taxes, can reduce returns, causing the portfolio to underperform its benchmark. Differences in the timing of trades between the portfolio manager and the index can also create tracking error. Furthermore, index reconstitution (when the index’s composition changes) can also lead to discrepancies between the portfolio and its benchmark. Finally, the manager’s active investment strategies, aimed at outperforming the benchmark, inherently introduce tracking error as a consequence of deviating from the index’s holdings.

Potential Pitfalls in Portfolio Optimization and Management

Avoiding certain pitfalls is crucial for successful portfolio management. Over-diversification, while seemingly beneficial, can dilute returns and increase management complexity without a commensurate reduction in risk. Conversely, under-diversification exposes the portfolio to excessive risk concentrated in a few assets. Ignoring transaction costs and taxes can significantly erode returns, impacting the portfolio’s overall performance. Failure to regularly rebalance the portfolio can lead to significant deviations from the target asset allocation, potentially increasing risk and reducing returns. Finally, relying solely on past performance to predict future returns is a fallacy; past performance is not indicative of future results. Many investment strategies that have performed exceptionally well in the past have subsequently underperformed, highlighting the limitations of using historical data as the sole basis for future investment decisions.

Final Conclusion

Ultimately, successful investment portfolio optimization requires a balanced approach. It’s a blend of rigorous analysis, informed decision-making, and a realistic understanding of market volatility and personal risk tolerance. By carefully considering asset allocation, risk management techniques, and the potential impact of market forces, investors can significantly enhance their chances of achieving long-term financial success. This process, while complex, is ultimately empowering, allowing investors to take control of their financial future.

Essential FAQs

What is the difference between active and passive portfolio management?

Active management involves actively trading securities to outperform the market, while passive management aims to match market performance through index funds or ETFs.

How often should I rebalance my portfolio?

Rebalancing frequency depends on your investment goals and risk tolerance. Common schedules are annually or semi-annually.

What are some common emotional biases that can hurt investment performance?

Fear, greed, overconfidence, and herd mentality are common emotional biases that can lead to poor investment decisions.

How can I determine my appropriate risk tolerance?

Consider your investment timeline, financial situation, and comfort level with potential losses to assess your risk tolerance. A financial advisor can also help.