Unlocking the secrets to successful business management often hinges on a deep understanding of financial intricacies. This Management Accounting Guide provides a clear and concise pathway to mastering the art of managing resources effectively. We’ll explore core principles, practical applications, and the latest technological advancements transforming this crucial field. Whether you’re a seasoned professional or just starting your journey, this guide offers valuable insights to enhance your decision-making prowess and drive organizational success.

From the fundamentals of cost accounting methods – including job order costing, process costing, and activity-based costing – to the strategic application of budgeting, forecasting, and performance measurement, this guide navigates the complexities of management accounting with clarity and precision. We’ll delve into crucial areas such as Cost-Volume-Profit (CVP) analysis and its role in informed decision-making, examining how to leverage data to optimize pricing strategies and resource allocation.

Introduction to Management Accounting

Management accounting is a vital function within any organization, providing crucial information for effective decision-making and strategic planning. It differs significantly from financial accounting in its focus and the audience it serves. While financial accounting primarily reports historical data to external stakeholders, management accounting focuses on providing forward-looking insights to internal users to enhance operational efficiency and profitability.

Management accounting uses various techniques to analyze and interpret data to support informed decisions. Its core principles center on relevance, timeliness, accuracy, and cost-effectiveness. The information generated should be pertinent to the specific decision at hand, delivered promptly to be useful, accurate to avoid misleading conclusions, and produced without excessive expense.

Definition and Purpose of Management Accounting

Management accounting is the process of identifying, measuring, analyzing, interpreting, and communicating financial information to managers for planning, controlling, and decision-making within an organization. Its purpose is to provide relevant and timely information to improve operational efficiency, enhance profitability, and achieve organizational goals. This information is used for internal purposes and is not subject to the same stringent regulations as financial accounting.

Differences Between Management and Financial Accounting

Several key differences distinguish management accounting from financial accounting. Financial accounting follows generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) or International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), producing standardized financial statements for external stakeholders like investors and creditors. These statements are historical in nature, providing a retrospective view of the company’s financial performance. In contrast, management accounting is not bound by GAAP or IFRS, allowing for greater flexibility in the types of information presented and the methods used to analyze it. Management accounting often incorporates estimations, projections, and non-financial data, offering a forward-looking perspective for internal decision-making. For example, financial accounting would report the total cost of goods sold for the past year, while management accounting might analyze the cost of goods sold per unit to identify areas for cost reduction.

Key Users of Management Accounting Information and Their Needs

Various individuals and departments within an organization utilize management accounting information. Top management relies on it for strategic planning and resource allocation, needing high-level summaries and forecasts to guide long-term decisions. Middle managers use it for operational control and performance evaluation, requiring detailed data on departmental performance and efficiency. For example, a production manager might use data on labor costs and machine downtime to improve productivity. Finally, lower-level managers and employees use it for daily operational decisions, needing specific information related to their immediate tasks. A sales representative, for example, might use data on sales trends and customer preferences to improve sales performance. Each level requires tailored information to fulfill their specific responsibilities and decision-making needs. The information provided must be relevant to their role and easily understandable.

Cost Accounting Methods

Cost accounting methods are crucial for businesses to understand their product or service costs, enabling informed pricing strategies, efficient resource allocation, and ultimately, improved profitability. Different methods suit different business structures and operational complexities. Choosing the right method depends heavily on the nature of the business and its production processes.

Job Order Costing

Job order costing tracks costs for individual projects or jobs. This method is best suited for businesses that produce unique or customized products or services, where each job has distinct characteristics and resource requirements. For example, a construction company building individual houses, a custom furniture maker, or a printing company producing personalized brochures would all benefit from using job order costing. The cost of each job is carefully accumulated throughout its lifecycle, from raw materials to direct labor and overhead. This detailed tracking allows for precise cost analysis for each individual project, aiding in pricing decisions and performance evaluation. However, it can be more administratively intensive than other methods, requiring meticulous record-keeping.

Process Costing

Process costing, in contrast, averages costs over a large number of identical units produced in a continuous process. This is ideal for businesses producing homogenous products in large quantities, such as food processing plants, chemical manufacturers, or oil refineries. Costs are tracked at each stage of the production process, and then the total costs are divided by the number of units produced to arrive at a cost per unit. While simpler to administer than job order costing, it provides less detailed cost information about individual units and may obscure inefficiencies within the production process. The averaging of costs can also mask variations in costs between different production batches or stages.

Activity-Based Costing (ABC)

Activity-based costing (ABC) assigns costs based on the activities that drive those costs. Unlike traditional costing methods that may rely on volume-based allocation, ABC focuses on identifying the activities involved in producing a product or service and then allocating costs to those activities. These activities are then linked to specific products or services based on their consumption of those activities. This provides a more accurate and detailed cost picture, especially in businesses with diverse product lines or complex production processes. While more complex to implement and maintain, ABC offers valuable insights into cost drivers and helps businesses make more informed decisions regarding pricing, product mix, and process improvement. For example, ABC might reveal that a particular product line consumes significantly more design and engineering time than initially assumed, leading to adjustments in pricing or production strategies.

Comparison of Cost Accounting Methods

| Method | Best Suited For | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Job Order Costing | Unique or customized products/services | Accurate cost tracking for individual jobs; precise pricing; aids in performance evaluation | Administratively intensive; requires meticulous record-keeping; not suitable for mass production |

| Process Costing | Mass production of homogenous products | Simple to administer; suitable for large-scale production; provides average cost per unit | Less detailed cost information for individual units; may obscure inefficiencies; cost averaging can be misleading |

| Activity-Based Costing (ABC) | Businesses with diverse product lines or complex processes | More accurate cost allocation; identifies cost drivers; supports better decision-making | Complex to implement and maintain; requires significant data collection and analysis; can be expensive |

Job Order Costing Example

Let’s consider a small carpentry business that creates custom bookshelves. They receive an order for a unique bookshelf (Job #123). The direct materials cost $150 (wood, screws, etc.), direct labor is $200 (carpenter’s wages), and allocated overhead is $50 (based on machine hours used). The total cost of Job #123 is $150 + $200 + $50 = $400. This allows the business to price the bookshelf accordingly, ensuring profitability while considering all associated costs. This process is repeated for each individual bookshelf order.

Budgeting and Forecasting

Budgeting and forecasting are crucial management accounting tools that enable businesses to plan for the future, allocate resources effectively, and monitor performance. A well-structured budget provides a roadmap for achieving organizational goals, while forecasting helps anticipate potential challenges and opportunities. This section will explore the processes involved in creating budgets and forecasts, and illustrate their practical application.

Master Budget Creation

The master budget is a comprehensive financial plan that integrates all aspects of a company’s operations. Its creation involves a series of steps, beginning with sales forecasting (discussed later) and extending to the development of various supporting budgets. These supporting budgets then feed into the overall master budget, providing a holistic view of expected financial performance. The process typically involves collaboration between different departments within the organization to ensure accuracy and alignment with overall strategic objectives. A typical sequence might involve developing sales forecasts, then production budgets, followed by direct materials, direct labor, and overhead budgets. Finally, a cash budget and budgeted financial statements (income statement and balance sheet) are created to complete the master budget.

Types of Budgets

Different budgets serve specific purposes within the overall financial planning process. These budgets offer a granular view of anticipated financial performance in various areas of the business.

- Operating Budget: This budget focuses on the revenue and expenses associated with the day-to-day operations of the business. It includes sales budgets, production budgets, and administrative expense budgets. For example, a restaurant’s operating budget would include projected food costs, labor costs, and rent.

- Capital Budget: This budget Artikels planned expenditures on long-term assets, such as property, plant, and equipment (PP&E). It involves evaluating potential investments and their projected returns. A manufacturing company’s capital budget might include funds allocated for purchasing new machinery or expanding facilities.

- Cash Budget: This budget projects cash inflows and outflows over a specific period. It’s crucial for managing liquidity and ensuring the company has sufficient cash to meet its obligations. A retailer’s cash budget would consider projected sales, payments to suppliers, and operating expenses, ensuring sufficient funds are available to cover payroll and rent.

Forecasting in Management Accounting

Forecasting plays a vital role in management accounting by providing insights into future performance. It helps businesses anticipate potential challenges, make informed decisions, and adapt to changing market conditions. Accurate forecasts are essential for effective resource allocation, budgeting, and strategic planning. By analyzing historical data and considering external factors like market trends and economic conditions, businesses can develop realistic forecasts that inform decision-making. The accuracy of forecasts directly impacts the reliability of the master budget and overall financial planning.

Sales Forecasting Using Historical Data

A simple sales forecast can be created using historical sales data. For example, let’s assume a company has recorded the following sales figures for the past four quarters:

| Quarter | Sales ($) |

|---|---|

| Q1 | 100,000 |

| Q2 | 120,000 |

| Q3 | 150,000 |

| Q4 | 180,000 |

A simple method is to calculate the average growth rate and apply it to the last quarter’s sales to predict the next quarter’s sales. In this example, the average quarterly growth rate is approximately 16.7% ((120,000-100,000)/100,000). Applying this rate to Q4 sales, the forecast for Q1 of the next year would be approximately $210,000 ($180,000 * 1.167). More sophisticated forecasting techniques, such as regression analysis, can also be employed for improved accuracy. However, this simple method provides a basic understanding of the process. It’s crucial to remember that this is a simplistic example and real-world forecasting often involves more complex models and considerations.

Performance Measurement and Evaluation

Effective performance measurement is crucial for the success of any organization. It provides insights into operational efficiency, identifies areas for improvement, and ultimately helps in achieving strategic goals. Management accounting plays a vital role in this process by providing the necessary data and analytical tools to assess performance accurately. This section explores key performance indicators (KPIs), variance analysis, and performance measurement frameworks.

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) in Management Accounting

KPIs are quantifiable metrics used to track and evaluate the performance of an organization, department, or specific process. They should be aligned with the overall strategic objectives and provide a clear picture of progress towards those goals. The selection of appropriate KPIs depends heavily on the context and the specific needs of the organization.

- Return on Investment (ROI): This classic KPI measures the profitability of an investment relative to its cost. It is calculated as Net Profit / Investment. A higher ROI indicates a more profitable investment.

- Return on Equity (ROE): This KPI measures the profitability of a company in relation to its shareholders’ equity. It’s calculated as Net Income / Shareholders’ Equity. A higher ROE suggests efficient use of shareholder funds.

- Customer Satisfaction (CSAT): This measures how satisfied customers are with a product or service. It’s often measured through surveys and feedback mechanisms. High CSAT scores generally correlate with increased customer loyalty and retention.

- Employee Turnover Rate: This KPI measures the percentage of employees who leave a company during a specific period. A high turnover rate can indicate issues with employee satisfaction, compensation, or management practices.

- Net Promoter Score (NPS): This metric measures customer loyalty and willingness to recommend a company’s products or services. It’s based on a simple survey question: “On a scale of 0 to 10, how likely are you to recommend [company/product] to a friend or colleague?” A higher NPS indicates stronger customer loyalty.

Variance Analysis

Variance analysis is a technique used to identify and analyze the differences between planned (budgeted) and actual results. By understanding the reasons behind these variances, management can take corrective actions and improve future performance. Variances are typically categorized as either favorable (positive impact on profit) or unfavorable (negative impact on profit). For example, a favorable sales variance indicates that actual sales exceeded budgeted sales.

The basic formula for variance analysis is: Variance = Actual Result – Budgeted Result

A detailed variance analysis might involve breaking down variances into various components, such as price variances and quantity variances, to pinpoint the specific causes of deviations from the budget. For instance, a negative variance in material costs could be due to either higher-than-expected material prices (price variance) or increased material usage (quantity variance).

Performance Measurement Frameworks: The Balanced Scorecard

The Balanced Scorecard is a widely used performance measurement framework that considers multiple perspectives, not just financial ones. It typically includes perspectives such as financial, customer, internal processes, and learning & growth. By incorporating these diverse perspectives, the Balanced Scorecard provides a more holistic view of organizational performance and helps ensure that strategic goals are aligned across all areas of the business. For example, a company might set targets for financial performance (e.g., increased revenue), customer satisfaction (e.g., improved CSAT scores), internal process efficiency (e.g., reduced production costs), and employee development (e.g., increased employee training hours). The Balanced Scorecard then tracks progress against these targets, providing a comprehensive assessment of overall performance.

Cost-Volume-Profit (CVP) Analysis

Cost-Volume-Profit (CVP) analysis is a crucial management accounting tool that examines the relationship between three key factors: costs, sales volume, and profit. Understanding this relationship allows businesses to make informed decisions regarding pricing, production levels, and overall profitability. This analysis simplifies complex business scenarios by focusing on the core drivers of profitability, providing a clear picture of the financial implications of various operational choices.

Break-Even Analysis

Break-even analysis is a core component of CVP analysis. It determines the point where total revenue equals total costs, resulting in neither profit nor loss. This crucial point helps businesses understand the minimum sales volume required to cover all expenses and begin generating profit. Understanding the break-even point provides a vital benchmark for evaluating business performance and setting realistic sales targets.

Applications of CVP Analysis in Decision-Making

CVP analysis offers valuable insights for various managerial decisions. For example, it can inform pricing strategies by demonstrating how different price points impact profitability at various sales volumes. It’s also instrumental in assessing the financial implications of expanding production capacity or introducing new products. Furthermore, CVP analysis can help businesses evaluate the impact of changes in variable costs, such as raw material prices, on overall profitability. A company considering launching a new product line, for example, can use CVP analysis to predict the required sales volume to break even and ensure profitability.

Break-Even Point Calculation

The break-even point can be calculated in both units and sales dollars. The formula for the break-even point in units is:

Break-even point (units) = Fixed Costs / (Selling Price per Unit – Variable Cost per Unit)

For example, if a company has fixed costs of $100,000, a selling price per unit of $50, and variable costs per unit of $30, the break-even point in units would be: $100,000 / ($50 – $30) = 5,000 units.

The break-even point in sales dollars is calculated as:

Break-even point (sales dollars) = Fixed Costs / ((Selling Price per Unit – Variable Cost per Unit) / Selling Price per Unit)

Using the same example, the break-even point in sales dollars would be: $100,000 / (($50 – $30) / $50) = $250,000.

Graphical Representation of Cost-Volume-Profit Relationships

A CVP graph visually depicts the relationship between cost, volume, and profit. The horizontal axis represents the sales volume (in units or dollars), while the vertical axis represents the total revenue and total costs. Three lines are typically plotted: a total revenue line (starting from the origin and sloping upwards), a total fixed cost line (a horizontal line), and a total cost line (starting at the point representing fixed costs on the vertical axis and sloping upwards). The point where the total revenue line intersects the total cost line represents the break-even point. The area between the total revenue line and the total cost line, to the right of the break-even point, represents profit, while the area between these lines to the left of the break-even point represents loss. The slope of the total revenue line reflects the selling price per unit, while the slope of the total cost line reflects the variable cost per unit. The vertical distance between the total cost line and the total revenue line at any given sales volume represents the profit or loss at that volume.

Decision Making using Management Accounting Information

Management accounting information plays a vital role in various business decisions, providing the necessary data for informed choices that drive profitability and efficiency. This section will explore how this information is utilized in pricing strategies, the concept of relevant costs, and the decision-making process in scenarios such as make-or-buy decisions.

Pricing Decisions using Management Accounting Information

Management accounting data, including cost information (both fixed and variable), desired profit margins, and market analysis, directly influences pricing strategies. Companies use cost-plus pricing, where a markup is added to the total cost of production, or value-based pricing, where prices are set based on perceived customer value. Accurate cost accounting is essential to determine the minimum price a company can charge while still achieving a desired profit. For instance, a company producing widgets with a total cost of $5 per unit and aiming for a 20% profit margin would price each widget at $6. This requires careful analysis of variable and fixed costs, understanding the cost drivers and the competitive landscape. Incorrect cost allocation can lead to underpricing and reduced profitability or overpricing and reduced market share.

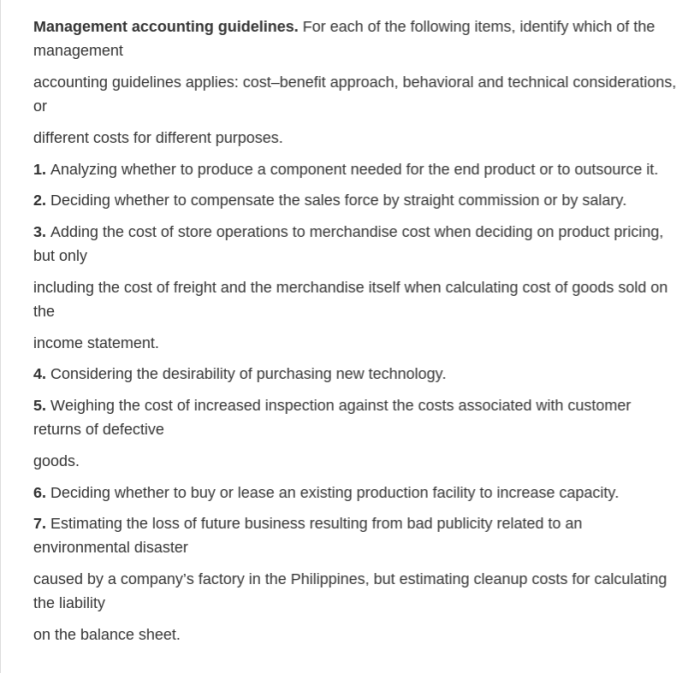

Relevant Costs and Benefits in Decision-Making

Relevant costs are those future costs that differ between decision alternatives. Conversely, irrelevant costs are those that remain unchanged regardless of the decision made. Similarly, relevant benefits are the future benefits that vary across different options. Only relevant costs and benefits should be considered when making a decision. For example, when deciding whether to replace an old machine, the purchase price of the new machine and the ongoing maintenance costs of both machines are relevant, while the sunk cost of the old machine is irrelevant. Similarly, the increased production capacity and potential revenue from the new machine represent relevant benefits. Ignoring irrelevant costs can lead to biased decision-making.

Examples of Decision-Making Situations

Management accounting is crucial in various decision-making situations. Examples include:

- Capital budgeting: Evaluating the profitability of long-term investments like new equipment or expansion projects. This involves analyzing projected cash flows, discounted cash flow analysis, and internal rate of return (IRR) calculations.

- Product mix decisions: Determining the optimal mix of products to produce, given resource constraints and demand forecasts. This utilizes data on production costs, selling prices, and demand projections to maximize profit.

- Make-or-buy decisions: Deciding whether to manufacture a product in-house or outsource its production. This involves comparing the relevant costs of both options.

- Pricing decisions: Setting prices that maximize profitability, considering costs, competition, and customer demand.

- Performance evaluation: Assessing the performance of different departments or business units using key performance indicators (KPIs).

Make-or-Buy Decision using Relevant Cost Analysis

The make-or-buy decision involves analyzing the relevant costs of producing a product internally versus purchasing it from an external supplier. A company should choose the option with the lower total relevant cost. Let’s consider a scenario where a company needs 10,000 units of a component. Producing internally would cost $5 per unit in direct materials, $3 per unit in direct labor, and $1 per unit in variable overhead. Fixed overhead allocated to this product would be $10,000. An external supplier offers the component for $9 per unit.

The relevant costs for making internally are: (10,000 units * ($5 + $3 + $1)) + $10,000 = $90,000.

The relevant costs for buying externally are: (10,000 units * $9) = $90,000.

In this specific example, both options have the same relevant cost. However, other factors, such as quality control, lead times, and potential capacity constraints, may influence the final decision. A sensitivity analysis, considering variations in cost and quantity, should also be performed to evaluate the robustness of the decision.

Management Accounting and Technology

The integration of technology has fundamentally reshaped management accounting, automating processes, enhancing data analysis capabilities, and ultimately improving decision-making. This section explores the impact of technology on various aspects of management accounting, highlighting both the opportunities and challenges presented by this evolving landscape.

Technology’s influence on management accounting processes is multifaceted. Automation tools streamline routine tasks such as data entry, report generation, and reconciliation, freeing up accountants to focus on higher-value activities like strategic analysis and forecasting. Real-time data access improves the timeliness of information, allowing for quicker responses to market changes and more agile decision-making. Furthermore, advanced technologies enable more sophisticated analysis of large datasets, providing deeper insights into business performance and identifying potential areas for improvement.

Software Used in Management Accounting

Many software solutions are specifically designed to support management accounting functions. These range from basic spreadsheet programs like Microsoft Excel, which are widely used for budgeting, forecasting, and simple cost analysis, to sophisticated Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems such as SAP and Oracle. ERP systems integrate various business functions, including finance, supply chain management, and human resources, providing a centralized platform for management accounting data. Specialized management accounting software packages offer more focused functionalities, such as advanced budgeting and forecasting tools, performance management dashboards, and cost allocation models. Cloud-based solutions are also increasingly popular, offering scalability, accessibility, and cost-effectiveness.

The Role of Data Analytics in Management Accounting

Data analytics plays a crucial role in extracting meaningful insights from the vast amounts of data generated by modern businesses. Management accountants leverage data analytics techniques to identify trends, patterns, and anomalies in financial and operational data. This includes techniques like regression analysis to predict future costs, data mining to identify cost drivers, and predictive modeling to forecast sales and profitability. Data visualization tools create clear and concise presentations of complex data, enabling better communication of findings to stakeholders. For example, a company might use data analytics to identify which product lines are most profitable, or to predict the impact of a price change on sales volume.

Challenges and Opportunities Presented by Technological Advancements

Technological advancements present both challenges and opportunities for management accountants. One significant challenge is the need for continuous learning and adaptation to new technologies and analytical techniques. The rapid pace of technological change requires management accountants to constantly update their skills and knowledge. Another challenge is the potential for data security breaches and the need for robust data governance procedures. However, the opportunities are significant. Technology enables more accurate and timely decision-making, improved efficiency, enhanced data-driven insights, and the ability to contribute more strategically to business goals. For example, the use of robotic process automation (RPA) can significantly reduce manual effort in routine tasks, freeing up time for more strategic initiatives. The use of AI-powered tools can improve forecasting accuracy and provide more insightful recommendations for business improvements. The successful adoption of technology requires investment in training, infrastructure, and robust data governance procedures, but the potential returns are substantial.

Concluding Remarks

This Management Accounting Guide serves as a comprehensive resource, equipping you with the knowledge and tools necessary to navigate the dynamic world of financial management. By understanding cost accounting, budgeting techniques, performance evaluation methods, and the strategic application of CVP analysis, you’ll be well-positioned to make data-driven decisions that drive profitability and sustainability. Embrace the power of informed financial management and propel your organization towards greater success.

FAQ Insights

What is the difference between management and financial accounting?

Management accounting focuses on internal decision-making, using data to improve efficiency and profitability. Financial accounting, conversely, provides external stakeholders with a summarized view of the company’s financial position for compliance and investment purposes.

How can I improve my budgeting accuracy?

Regularly review and adjust your budget based on actual performance, incorporate historical data and market trends into your forecasts, and involve key stakeholders in the budgeting process for better buy-in and accuracy.

What are some common pitfalls to avoid in CVP analysis?

Avoid assuming fixed costs remain constant across all production levels, and remember that CVP analysis relies on simplified assumptions and may not always reflect real-world complexities.