Ratio Analysis Interpretation Guide: Forget dry spreadsheets and yawn-inducing financial jargon! This guide unveils the surprisingly entertaining world of ratio analysis, transforming complex financial data into a captivating narrative. We’ll explore the secrets behind liquidity, solvency, and profitability ratios, revealing how these seemingly mundane numbers can tell a company’s thrilling (or terrifying) story. Prepare for a rollercoaster ride through the world of financial analysis – buckle up, it’s going to be a wild ride!

From deciphering the cryptic messages hidden within balance sheets to mastering the art of interpreting key ratios, this guide provides a clear, concise, and (dare we say) enjoyable pathway to understanding the financial health of any business. Whether you’re a seasoned financial analyst or a curious newcomer, get ready to unlock the power of numbers and discover the hidden narratives within financial statements. We’ll tackle everything from liquidity ratios that reveal a company’s short-term survival chances to solvency ratios that expose its long-term prospects, all while keeping things engaging and informative.

Introduction to Ratio Analysis

Ratio analysis: it’s not just for accountants anymore! Think of it as the financial detective work that helps businesses, investors, and even creditors understand a company’s performance and financial health. It’s a powerful tool that transforms complex financial statements into digestible, actionable insights, allowing for informed decisions and, let’s be honest, a bit less financial anxiety.

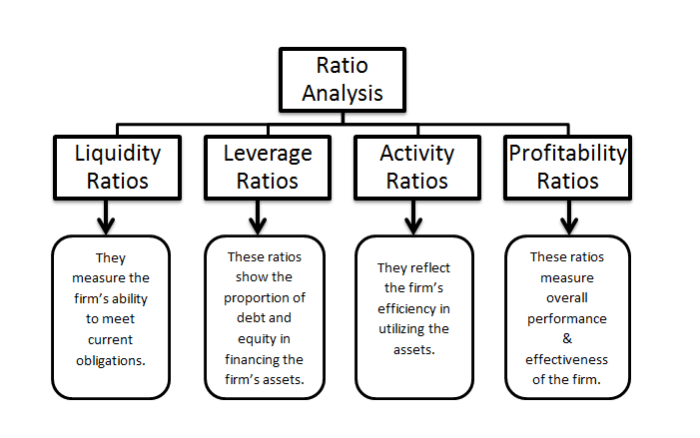

Ratio analysis is the process of comparing line items in a company’s financial statements—like the balance sheet and income statement—to derive meaningful relationships and insights. These ratios act as financial barometers, providing a snapshot of a company’s profitability, liquidity, solvency, and efficiency. Its applications are incredibly broad, ranging from assessing investment opportunities to monitoring credit risk. Essentially, it’s a way to see beyond the numbers and understand the story they tell.

Types of Businesses Utilizing Ratio Analysis

A wide array of businesses, from the smallest corner store to the largest multinational corporation, rely on ratio analysis. Small businesses use it to track their progress, secure loans, and make crucial operational decisions. Large corporations employ it for strategic planning, performance evaluation, and attracting investors. For example, a rapidly growing tech startup might use ratio analysis to demonstrate its potential for profitability to venture capitalists, while a mature manufacturing company might use it to identify areas for cost reduction and efficiency improvements. Even non-profit organizations utilize ratio analysis to showcase their financial stability and responsible use of donations. In short, if a business has financial statements, it can benefit from the insights of ratio analysis.

Liquidity Ratios

Liquidity ratios are the financial equivalent of a magician’s disappearing act – except instead of rabbits, we’re talking about a company’s ability to pay its short-term debts. These ratios reveal whether a company can meet its immediate obligations without resorting to drastic measures, like selling off Grandma’s prized porcelain collection (or, you know, more serious things like laying off employees). Understanding liquidity is crucial for investors, creditors, and the company itself to gauge its financial health and stability.

Current Ratio and Quick Ratio Calculations and Interpretations

The current ratio and quick ratio are two prominent liquidity metrics, each offering a slightly different perspective on a company’s short-term solvency. Think of them as two detectives investigating the same crime scene, but with different magnifying glasses. The current ratio provides a broad overview, while the quick ratio focuses on the most readily available assets.

The current ratio is calculated by dividing current assets by current liabilities:

Current Ratio = Current Assets / Current Liabilities

A current ratio of 2.0, for instance, suggests that a company has twice as many current assets as current liabilities. Generally, a higher ratio is considered better, indicating a greater capacity to meet short-term obligations. However, an excessively high ratio might also signal inefficient use of assets. Imagine a company hoarding cash – it’s technically liquid, but not necessarily profitable.

The quick ratio, also known as the acid-test ratio, is a more conservative measure. It excludes inventory from current assets because inventory might not be easily converted into cash. The calculation is:

Quick Ratio = (Current Assets – Inventory) / Current Liabilities

The quick ratio offers a more stringent assessment of immediate liquidity. A higher quick ratio indicates a stronger ability to meet short-term obligations even if the sale of inventory is delayed or problematic. For example, a company selling perishable goods might have a lower quick ratio than one selling durable goods.

Comparison of Liquidity Ratios

The following table summarizes the strengths and weaknesses of different liquidity ratios. Remember, these ratios should be interpreted in context, considering the industry, economic conditions, and the company’s specific business model. No single ratio tells the whole story; it’s the combination that paints a complete picture.

| Ratio | Strengths | Weaknesses | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Ratio | Easy to calculate; provides a broad overview of liquidity. | Includes less liquid assets like inventory; can be misleading if inventory is slow-moving or obsolete. | Initial screening of liquidity; comparing companies within the same industry. |

| Quick Ratio | More conservative; focuses on readily available assets; less susceptible to inventory valuation issues. | Excludes inventory, potentially underestimating liquidity in some industries (e.g., retail). | Assessing immediate short-term solvency; comparing companies with different inventory management practices. |

| Cash Ratio (Cash + Marketable Securities / Current Liabilities) | Most conservative; focuses solely on the most liquid assets. | May underestimate overall liquidity as it ignores other liquid assets. | Evaluating the ability to meet immediate obligations with the most liquid assets. |

Solvency Ratios

Solvency ratios, unlike those pesky liquidity ratios that only care about short-term survival, are the seasoned veterans of financial analysis. They peer into the crystal ball of a company’s long-term future, assessing its ability to meet its long-term obligations and weather even the most turbulent economic storms. Think of them as the financial equivalent of a seasoned mountain climber, assessing the stability of the entire mountain, not just the next foothill. Ignoring them is like ignoring the avalanche warning signs – potentially disastrous!

Solvency ratios provide a crucial perspective on a company’s capital structure and its ability to withstand financial distress. They delve into the heart of a company’s debt burden, examining the delicate balance between borrowed funds and equity financing. A healthy balance is crucial for long-term stability, allowing the company to navigate unforeseen challenges without collapsing under the weight of its obligations. It’s a delicate dance, and these ratios help us understand the rhythm.

Debt-to-Equity Ratio

The debt-to-equity ratio is a classic showdown between borrowed money and shareholder investment. It’s calculated by dividing total liabilities by shareholder equity. A higher ratio suggests the company relies heavily on debt financing, potentially increasing its financial risk. Imagine a tightrope walker – the higher the ratio, the higher the risk of a spectacular fall. For example, a company with a debt-to-equity ratio of 2.0 means it has twice as much debt as equity, indicating a significantly higher level of financial leverage and risk. Conversely, a ratio closer to 0 suggests a more conservative approach, relying less on debt and more on equity financing.

Times Interest Earned Ratio

The times interest earned ratio, also known as the interest coverage ratio, measures a company’s ability to pay its interest expenses with its earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT). It’s calculated by dividing EBIT by interest expense. This ratio reveals how comfortably a company can handle its interest payments. A higher ratio indicates greater ability to meet interest obligations. Think of it as a financial stress test for a company’s heart – a higher number shows a healthier, more resilient financial system. For instance, a ratio of 5 suggests that a company’s EBIT is five times greater than its interest expense, demonstrating a strong capacity to meet interest payments.

Debt-to-Asset Ratio

The debt-to-asset ratio is a broader measure of a company’s solvency, showing the proportion of a company’s assets financed by debt. It’s calculated by dividing total liabilities by total assets. This ratio offers a comprehensive view of the company’s financial leverage. A higher ratio implies a greater reliance on debt to finance its assets, which increases the company’s financial risk. It’s like looking at the entire financial picture, not just individual parts. A company with a debt-to-asset ratio of 0.6 means that 60% of its assets are financed by debt.

Factors Influencing Solvency Ratios

Understanding the factors influencing solvency ratios is crucial for accurate interpretation. These ratios aren’t static; they’re dynamic, reacting to a variety of internal and external forces. Ignoring these influences is like trying to navigate a ship without a compass – a recipe for disaster.

- Capital Structure: The mix of debt and equity financing significantly impacts solvency ratios. A higher proportion of debt generally leads to higher ratios.

- Profitability: Higher profitability generally improves solvency ratios by increasing the ability to cover interest payments and reduce debt.

- Economic Conditions: Recessions and economic downturns can negatively impact profitability and increase the risk of default, affecting solvency ratios.

- Industry Norms: Comparing a company’s solvency ratios to industry averages provides valuable context and helps identify potential areas of concern.

- Management Decisions: Decisions regarding capital expenditures, dividend payments, and debt refinancing directly impact solvency.

Profitability Ratios

Profitability ratios, the unsung heroes of financial analysis, reveal the true earning power of a company. They don’t just tell you if a company is making money; they whisper secrets about operational efficiency, pricing strategies, and the overall effectiveness of management. Ignoring them is like trying to navigate a ship without a compass – you might get lucky, but it’s unlikely.

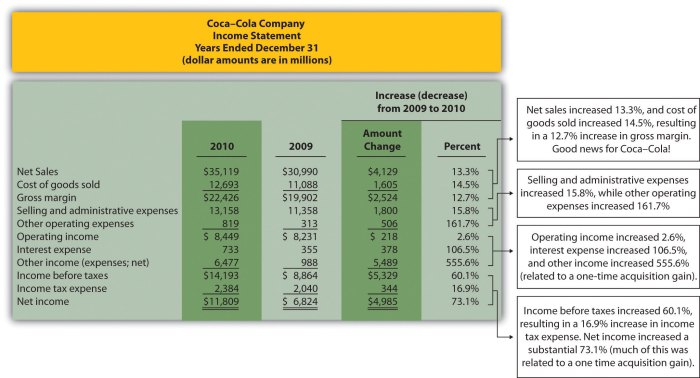

Profitability ratios are calculated using data from the income statement and balance sheet, providing a comprehensive picture of a company’s ability to generate profit from its operations. They are essential for investors, creditors, and management alike in making informed decisions about the company’s financial health and future prospects. Let’s dive into the delicious details.

Gross Profit Margin

The gross profit margin measures the efficiency of a company’s production and sales processes. It shows the percentage of revenue remaining after deducting the cost of goods sold (COGS). A higher gross profit margin generally indicates greater efficiency in production or a stronger pricing strategy. The calculation is straightforward:

Gross Profit Margin = (Revenue – Cost of Goods Sold) / Revenue * 100%

For example, if a company has revenue of $1,000,000 and COGS of $600,000, its gross profit margin is 40%. This suggests that for every dollar of revenue, 40 cents are left to cover operating expenses and generate profit. A consistently high gross profit margin can be a strong indicator of a company’s competitive advantage.

Net Profit Margin

The net profit margin, the ultimate test of profitability, reveals the percentage of revenue remaining after all expenses, including taxes and interest, are deducted. It’s the bottom line, the grand finale, the *money* money. The higher the net profit margin, the better the company is at converting revenue into actual profit.

Net Profit Margin = Net Profit / Revenue * 100%

Let’s say our company from the previous example has a net profit of $100,000. Its net profit margin would be 10% ($100,000 / $1,000,000 * 100%). This means that for every dollar of revenue, only 10 cents are pure profit. A low net profit margin might indicate high operating costs or intense competition.

Return on Equity (ROE), Ratio Analysis Interpretation Guide

Return on equity (ROE) is a crucial measure for investors, showcasing how effectively a company uses shareholder investments to generate profits. It’s a powerful indicator of management’s ability to leverage equity to create value. A higher ROE generally signals superior management and a stronger investment opportunity.

Return on Equity = Net Profit / Shareholder Equity * 100%

Assuming our hypothetical company has shareholder equity of $500,000, its ROE would be 20% ($100,000 / $500,000 * 100%). This means that for every dollar of shareholder equity, the company generated 20 cents of profit. A consistently high ROE attracts investors and indicates strong financial performance.

Industry Comparison of Profitability

To illustrate how profitability varies across industries, let’s consider hypothetical data for three different sectors:

| Industry | Gross Profit Margin (%) | Net Profit Margin (%) | Return on Equity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luxury Goods | 60 | 25 | 30 |

| Grocery Retail | 25 | 5 | 10 |

| Technology | 50 | 15 | 20 |

This hypothetical data shows that the luxury goods industry boasts significantly higher profit margins and ROE compared to grocery retail, reflecting the higher pricing power and potentially lower operating costs in the luxury sector. The technology sector sits comfortably in the middle, indicating a balance between profitability and competitive pressures. Remember, these are hypothetical figures; actual industry data will vary considerably.

Activity Ratios (Efficiency Ratios)

Activity ratios, also known as efficiency ratios, are the unsung heroes of financial analysis. While profitability and solvency ratios grab the headlines, activity ratios quietly reveal how effectively a company utilizes its assets to generate sales and cash flow. They’re like the efficiency experts of the corporate world, meticulously scrutinizing every move to identify areas for improvement and maximizing returns. Think of them as the company’s personal trainers, pushing for optimal performance.

Activity ratios provide crucial insights into a company’s operational efficiency, offering a glimpse into the inner workings of its day-to-day operations. By analyzing how quickly a company converts its assets into sales, we can assess its operational effectiveness and identify potential bottlenecks. A company might be highly profitable, but if it’s incredibly slow at turning inventory or collecting receivables, those profits could be significantly higher with improved efficiency.

Inventory Turnover

Inventory turnover measures how many times a company sells and replaces its inventory during a specific period. A high inventory turnover ratio generally indicates strong sales and efficient inventory management. Conversely, a low ratio might suggest slow-moving inventory, potential obsolescence, or overstocking, leading to increased storage costs and potential losses. The formula is: Cost of Goods Sold / Average Inventory. For example, a company with a cost of goods sold of $1,000,000 and average inventory of $200,000 has an inventory turnover of 5, meaning they sold and replaced their inventory five times during the period. A significantly lower turnover than industry averages might indicate a need for a strategic inventory review and potentially a marketing push to boost sales of slow-moving items. A remarkably high turnover, however, could signal that the company is understocked, risking lost sales due to insufficient inventory to meet demand.

Accounts Receivable Turnover

Accounts receivable turnover reflects how efficiently a company collects payments from its customers. A high ratio suggests effective credit policies and efficient collection procedures. A low ratio, on the other hand, may point to lax credit policies, difficulties in collecting payments, or even potentially bad debts. The formula is: Net Credit Sales / Average Accounts Receivable. Imagine a company with net credit sales of $500,000 and average accounts receivable of $50,000. Their accounts receivable turnover is 10, suggesting they collect their receivables ten times a year. A consistently low turnover warrants investigation; perhaps the company needs to tighten its credit policies or improve its debt collection processes. Conversely, an extremely high turnover, while seemingly positive, might indicate that the company is being overly strict with credit, potentially alienating valuable customers.

Asset Turnover

Asset turnover showcases how effectively a company utilizes its assets to generate sales. It measures the sales generated for every dollar invested in assets. A high ratio generally implies efficient asset utilization, while a low ratio might suggest underutilized assets or inefficient operations. The formula is: Net Sales / Average Total Assets. For instance, a company with net sales of $2,000,000 and average total assets of $1,000,000 has an asset turnover of 2. This means they generate $2 in sales for every $1 invested in assets. A low asset turnover might indicate that the company has excessive assets relative to its sales, prompting a review of its investment strategy. A high asset turnover, however, is not always unequivocally positive; it might also indicate that the company is operating with a dangerously low level of assets, leaving it vulnerable to disruptions.

Interpreting Ratio Analysis Results: Ratio Analysis Interpretation Guide

Unraveling the financial mysteries hidden within a company’s numbers is like deciphering an ancient scroll – exciting, challenging, and potentially rewarding! But unlike Indiana Jones, you don’t need a whip; you need a keen eye for detail and a knack for combining insights. This section will guide you through the process of making sense of your ratio analysis, transforming raw data into actionable intelligence.

Interpreting ratio analysis results involves more than just looking at individual ratios in isolation. Think of it as a financial detective story; each ratio provides a clue, but only by piecing them together can you solve the case and understand the complete financial picture. We’ll explore how to combine insights from different ratio categories to build a comprehensive assessment and highlight the crucial role of benchmarks and historical trends in your investigations.

Combining Insights from Different Ratio Categories

A holistic financial assessment requires a symphony of ratios, not a solo performance by a single metric. For example, high profitability ratios (suggesting strong earnings) might be less impressive if coupled with low liquidity ratios (indicating potential cash flow problems). Similarly, excellent solvency ratios (implying a healthy debt structure) might be overshadowed by poor activity ratios (signaling operational inefficiencies). By analyzing ratios across categories – liquidity, solvency, profitability, and activity – you create a more nuanced understanding of the company’s overall financial health. This integrated approach allows you to identify strengths and weaknesses, uncover potential risks, and make more informed decisions. Ignoring the interplay between different ratio categories is like trying to understand a play by only reading one character’s lines – you miss the bigger picture and the subtle nuances of the narrative.

The Importance of Industry Benchmarks and Historical Trends

Comparing a company’s ratios against industry averages provides valuable context. A high current ratio might seem fantastic in isolation, but it’s less impressive if all competitors have even higher ratios. Similarly, tracking a company’s ratios over time reveals trends and patterns that single-year snapshots miss. A declining profit margin, for example, could indicate a serious problem, even if the current margin is still above the industry average. Using both benchmarks and historical trends allows for a more accurate assessment of a company’s performance relative to its peers and its own past performance. Think of it as comparing your performance to the class average and your own previous scores – both pieces of information contribute to a complete understanding.

Hypothetical Case Study: Acme Corporation

Let’s analyze Acme Corporation, a hypothetical widget manufacturer, using ratio analysis to illustrate its power. The following table shows Acme’s key ratios for the past two years, along with industry averages:

| Ratio | Acme Corp (Year 1) | Acme Corp (Year 2) | Industry Average |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Ratio | 1.8 | 1.5 | 2.0 |

| Debt-to-Equity Ratio | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.6 |

| Return on Assets (ROA) | 10% | 8% | 12% |

| Inventory Turnover | 5 | 4 | 6 |

Acme’s current ratio has declined, falling below the industry average, suggesting a potential liquidity issue. Simultaneously, its debt-to-equity ratio has increased, indicating higher financial risk. While its ROA remains positive, it’s also decreased and is below the industry average, signaling weakening profitability. The inventory turnover ratio has also fallen, pointing to potential overstocking or slower sales. This combined analysis suggests that Acme needs to address its liquidity, manage its debt more effectively, and improve its operational efficiency to remain competitive. The story told by the ratios is far more compelling and insightful than any single ratio could tell on its own.

Limitations of Ratio Analysis

Ratio analysis, while a powerful tool for financial sleuthing, isn’t without its quirks and limitations. Think of it as a highly sophisticated magnifying glass – it reveals a lot, but it doesn’t tell the whole story, and sometimes the magnification can distort the view. A thorough understanding of these limitations is crucial to avoid drawing inaccurate or misleading conclusions.

Ratio analysis relies heavily on historical financial data, which, as any seasoned accountant will tell you, can be as reliable as a chocolate teapot in a hurricane. The past is not necessarily a predictor of the future, and ratios calculated from past performance may not reflect current or future realities. Furthermore, the very act of focusing solely on numbers can blind us to crucial qualitative aspects of a business, leading to a skewed perspective.

Accounting Methodologies and Their Influence

Different accounting methods can significantly impact the calculated ratios. For instance, using FIFO (First-In, First-Out) versus LIFO (Last-In, First-Out) inventory valuation can dramatically affect the cost of goods sold and, consequently, profitability ratios. A company choosing one method over another might not be acting deceptively, but the resulting ratios will differ, potentially leading to contrasting interpretations. Similarly, the choice of depreciation methods can influence asset values and profitability figures. Imagine comparing two otherwise identical companies – one using straight-line depreciation and the other using accelerated depreciation. Their ratios will tell different stories, even though the underlying business performance might be similar. Therefore, comparing ratios across companies requires a careful consideration of their respective accounting policies.

Industry Variations and Benchmarking

Comparing a bakery’s profitability ratios to those of a tech startup is like comparing apples and spaceships. Each industry operates under unique conditions, with different levels of capital intensity, operating cycles, and competitive pressures. A high debt-to-equity ratio might be perfectly acceptable in a capital-intensive industry like manufacturing, but it could be a major red flag in a less asset-heavy industry. Benchmarking against the right industry peers is crucial for meaningful interpretation. Blindly comparing ratios across diverse sectors can lead to wildly inaccurate conclusions. For example, a high inventory turnover ratio might indicate efficiency in one industry but inefficiency in another, depending on the nature of the inventory and industry norms.

Qualitative Factors: The Missing Piece of the Puzzle

While ratios provide a quantitative snapshot of a company’s financial health, they often fail to capture the qualitative aspects that can significantly impact its future prospects. These include management quality, employee morale, brand reputation, customer loyalty, and the overall economic climate. A company with excellent ratios might still be facing challenges due to poor management or negative industry trends. Conversely, a company with less impressive ratios might be poised for growth due to a strong brand or innovative product line. Ignoring these qualitative factors can lead to a severely incomplete and potentially misleading analysis. Consider a small, rapidly growing tech company with high debt and low profitability in its early stages. While the ratios might appear alarming, the company’s strong growth potential and innovative technology could make it a promising investment, a fact that purely quantitative analysis might miss.

Data Limitations and Timeliness

The accuracy and timeliness of the financial data used in ratio analysis are paramount. Outdated or inaccurate data can lead to erroneous conclusions. Furthermore, many ratios are based on historical data, which may not accurately reflect current or future performance. A company’s financial position can change rapidly, rendering some ratios obsolete almost immediately. For instance, a company might have a strong liquidity ratio at the beginning of the year but experience a sudden downturn later on, rendering the initial ratio irrelevant. Therefore, it’s essential to use the most recent and reliable data available and to consider the potential for change.

Visual Representation of Ratio Analysis

Ratio analysis, while intellectually stimulating (in a nerdy, spreadsheet-loving kind of way), can be a bit of a snooze-fest when presented solely as a table of numbers. Fear not, fellow financial analysts! Visual representations can transform your dry data into dynamic, easily digestible insights. Let’s explore how to visually showcase your hard-earned ratio calculations.

Line Graphs for Tracking Ratio Trends Over Time

Line graphs are the unsung heroes of visualizing trends. They’re perfect for showing how a specific ratio changes over several accounting periods (e.g., years, quarters). Imagine you’re tracking a company’s current ratio over five years. The horizontal (x-axis) would represent the years (Year 1, Year 2, Year 3, Year 4, Year 5), while the vertical (y-axis) would represent the current ratio value. Each data point (year and corresponding ratio) is plotted, and the points are connected to form a line. A rising line indicates improvement in the ratio, while a falling line suggests a decline. Clear labeling of both axes is crucial; don’t make your audience play “guess the axis.” For example, you might label the y-axis as “Current Ratio” and include a clear scale (e.g., 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5). By visually inspecting the line’s slope, one can quickly assess whether the company’s liquidity is improving or deteriorating. For instance, a consistently upward-sloping line for the current ratio suggests improved liquidity over time.

Bar Charts for Comparing Company Performance

Bar charts are the go-to choice for comparing different entities on a single ratio. Let’s say you want to compare the profitability of three companies (Company A, Company B, Company C) using their return on equity (ROE). The x-axis would represent the companies (Company A, Company B, Company C), while the y-axis would represent the ROE (expressed as a percentage, e.g., 10%, 15%, 20%). Each company would have a corresponding bar whose height reflects its ROE. A taller bar indicates a higher ROE, suggesting superior profitability. Again, clear and concise labeling is essential. A legend might be needed if you are comparing multiple ratios for the same company. For instance, if you were also plotting the Return on Assets (ROA) for the same companies, the legend would clarify which bar corresponds to which ratio for each company. Imagine Company A boasts a significantly taller bar than B and C on the ROE chart – that’s a visual shout-out to its superior profitability!

Last Point

So, there you have it – a whirlwind tour through the surprisingly exciting world of ratio analysis! We’ve journeyed from the basics of understanding financial statements to interpreting complex ratios and even considered the limitations of this powerful tool. Remember, while numbers speak volumes, they don’t tell the whole story. Always consider the context, the industry benchmarks, and those pesky qualitative factors. Mastering ratio analysis isn’t just about crunching numbers; it’s about unlocking the narrative hidden within them, a narrative that can lead to informed decisions and potentially, even riches (or at least a much-needed raise!). Happy analyzing!

General Inquiries

What’s the difference between a current ratio and a quick ratio?

The current ratio is a broader measure of short-term liquidity, including all current assets. The quick ratio is stricter, excluding less liquid assets like inventory, giving a more conservative view of immediate payment ability.

Can I use ratio analysis to compare companies in different industries?

While direct comparisons are tricky due to industry variations, ratio analysis is still valuable for benchmarking against industry averages and identifying relative strengths and weaknesses within a specific sector.

How often should I perform ratio analysis?

Frequency depends on your needs. Regular monitoring (monthly, quarterly, annually) provides valuable insights into trends, while less frequent analysis might suffice for long-term strategic decisions.

What are some common pitfalls to avoid when interpreting ratios?

Beware of using ratios in isolation; consider industry context, historical trends, and qualitative factors. Also, be mindful of accounting methods which can significantly influence results.