Unlocking the secrets of a company’s financial health requires more than just glancing at the bottom line. Ratio analysis provides a powerful lens through which to examine a business’s performance, liquidity, solvency, and profitability. By systematically comparing different financial metrics, we gain valuable insights into operational efficiency, risk assessment, and overall financial strength. This guide delves into the core techniques of ratio analysis, equipping you with the knowledge to interpret financial statements with confidence and make informed decisions.

We will explore various ratio categories, from assessing short-term liquidity with current and quick ratios to evaluating long-term solvency using debt-to-equity and times interest earned ratios. Understanding profitability through gross, operating, and net profit margins will be equally crucial. Furthermore, we will examine efficiency ratios that shed light on how effectively a company manages its assets and liabilities. The guide will also address the importance of contextualizing ratio analysis with industry benchmarks and qualitative factors for a holistic perspective.

Introduction to Ratio Analysis Techniques

Ratio analysis is a crucial tool in financial decision-making, providing insights into a company’s performance, profitability, and financial health. By examining the relationships between different financial statement items, analysts can assess a company’s strengths and weaknesses, identify potential risks, and make informed judgments about its future prospects. This technique is invaluable for investors, creditors, and managers alike, allowing them to compare a company’s performance to its industry peers, track its progress over time, and make strategic decisions.

Ratio analysis offers a standardized way to evaluate financial data, transforming raw numbers into meaningful metrics that can be easily understood and compared. It allows for a more comprehensive understanding of a company’s financial position than simply reviewing the balance sheet or income statement in isolation. Furthermore, consistent application of ratio analysis across different periods and companies enables effective benchmarking and trend analysis.

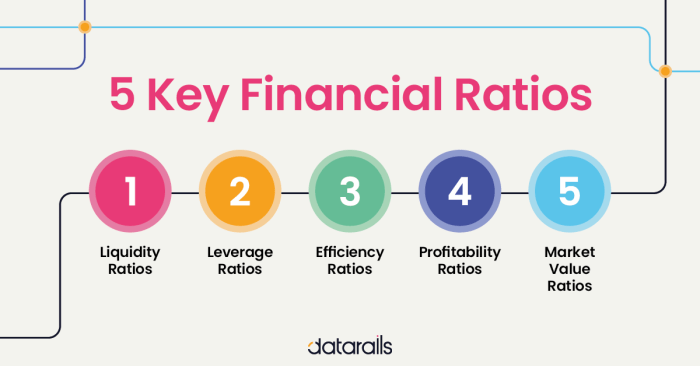

Types of Financial Ratios

Financial ratios are broadly categorized into several groups, each offering a unique perspective on a company’s financial standing. Understanding these categories and the specific ratios within them is key to conducting a thorough analysis.

| Ratio Category | Ratio Name | Formula | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquidity Ratios | Current Ratio | Current Assets / Current Liabilities | Measures a company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations. A higher ratio generally indicates better liquidity. |

| Liquidity Ratios | Quick Ratio (Acid-Test Ratio) | (Current Assets – Inventory) / Current Liabilities | A more conservative measure of liquidity, excluding less liquid inventory. |

| Profitability Ratios | Gross Profit Margin | (Revenue – Cost of Goods Sold) / Revenue | Indicates the profitability of sales after deducting the direct costs of producing goods or services. |

| Profitability Ratios | Net Profit Margin | Net Income / Revenue | Shows the percentage of revenue remaining as profit after all expenses are deducted. |

| Solvency Ratios | Debt-to-Equity Ratio | Total Debt / Total Equity | Measures the proportion of a company’s financing that comes from debt compared to equity. A higher ratio suggests higher financial risk. |

| Solvency Ratios | Times Interest Earned | EBIT / Interest Expense | Indicates a company’s ability to cover its interest payments with its earnings before interest and taxes. |

| Activity Ratios | Inventory Turnover | Cost of Goods Sold / Average Inventory | Measures how efficiently a company manages its inventory. A higher turnover suggests efficient inventory management. |

| Activity Ratios | Days Sales Outstanding (DSO) | (Accounts Receivable / Revenue) * Number of Days | Indicates the average number of days it takes a company to collect payment from its customers. A lower DSO is generally preferred. |

Importance of Consistent Data Sources

Using consistent data sources is paramount when performing ratio analysis. Inconsistent data will lead to inaccurate and unreliable results, rendering the analysis meaningless. For example, using data from different accounting periods or employing varying accounting methods will distort the relationships between financial statement items and invalidate any comparisons. To ensure accuracy and comparability, all ratios should be calculated using data from the same financial statements, prepared using consistent accounting principles and reporting periods. This consistency is crucial for identifying meaningful trends and making sound financial decisions. Using data from reputable sources, such as a company’s annual reports or audited financial statements, is also essential to maintain the integrity of the analysis.

Liquidity Ratios

Liquidity ratios are crucial financial metrics that assess a company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations. They provide insights into a firm’s capacity to pay off its debts that are due within a year. Analyzing these ratios helps investors, creditors, and management understand the company’s short-term financial health and stability. A strong liquidity position indicates a lower risk of default on short-term debts.

Liquidity ratios are calculated using data readily available on a company’s balance sheet. Understanding these ratios is essential for making informed financial decisions, whether you are an investor evaluating potential investments or a lender assessing creditworthiness. The most commonly used liquidity ratios are the current ratio, the quick ratio, and the cash ratio.

Key Liquidity Ratios: Current Ratio, Quick Ratio, and Cash Ratio

The current ratio, quick ratio, and cash ratio are all measures of a company’s short-term liquidity. However, they differ in the assets they consider, reflecting varying degrees of liquidity. Each ratio provides a unique perspective on a company’s ability to meet its immediate financial obligations.

- Current Ratio: This is the most widely used liquidity ratio. It measures the ability of a company to pay its short-term liabilities (due within one year) with its current assets (assets that can be converted into cash within one year). The formula is:

Current Ratio = Current Assets / Current Liabilities

A higher current ratio generally indicates greater liquidity. However, an excessively high ratio might suggest inefficient use of assets.

- Quick Ratio (Acid-Test Ratio): This ratio is a more stringent measure of liquidity than the current ratio. It excludes inventories from current assets, as inventories may not be easily or quickly converted into cash. The formula is:

Quick Ratio = (Current Assets – Inventories) / Current Liabilities

The quick ratio provides a more conservative estimate of a company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations.

- Cash Ratio: This is the most conservative liquidity ratio. It only considers the most liquid assets – cash and cash equivalents – in relation to current liabilities. The formula is:

Cash Ratio = (Cash + Cash Equivalents) / Current Liabilities

A high cash ratio suggests a very strong ability to meet short-term obligations, but it may also indicate that the company is not efficiently utilizing its assets.

Assessing Short-Term Debt-Paying Ability with Liquidity Ratios

Liquidity ratios are vital tools for assessing a company’s ability to meet its short-term debt obligations. Low liquidity ratios signal potential problems in meeting short-term payments, which can lead to financial distress. Conversely, healthy liquidity ratios suggest a lower risk of default and improved financial stability. Creditors often use liquidity ratios to evaluate the creditworthiness of a company before extending loans. Investors also utilize these ratios to assess the risk associated with investing in a company. Analyzing trends in liquidity ratios over time is particularly insightful, as it can reveal improvements or deteriorations in a company’s short-term financial health.

Impact of Inventory Changes on Liquidity Ratios

Changes in inventory levels significantly affect liquidity ratios. For example, consider a hypothetical company, “ABC Corp,” that experiences a surge in sales. To meet this increased demand, ABC Corp increases its inventory levels. This initially lowers the quick ratio and current ratio because inventories are included in current assets but are not considered in the quick ratio. However, if the increased sales translate into increased cash flow, the current and cash ratios will improve, compensating for the initial drop. Conversely, if sales do not increase proportionally to the inventory buildup, then the liquidity ratios will worsen, reflecting a potential problem with inventory management. A large buildup of unsold inventory ties up capital, reducing the company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations. Therefore, monitoring inventory levels and their impact on liquidity ratios is critical for effective financial management.

Solvency Ratios

Solvency ratios are crucial indicators of a company’s long-term financial health and its ability to meet its long-term obligations. Unlike liquidity ratios, which focus on short-term obligations, solvency ratios provide insights into a company’s capital structure, debt levels, and overall financial stability. Understanding these ratios is vital for both creditors assessing lending risks and investors evaluating investment opportunities.

Solvency ratios assess a company’s ability to meet its long-term financial obligations. These ratios help stakeholders understand the company’s financial leverage and its capacity to withstand economic downturns or unexpected financial pressures. A strong solvency position indicates a lower risk of default or bankruptcy.

Primary Solvency Ratios

Several key solvency ratios provide a comprehensive view of a company’s long-term financial health. These ratios utilize data from the balance sheet and income statement to paint a picture of the company’s capital structure and its ability to service its debt. Analyzing these ratios in conjunction with other financial metrics provides a more holistic assessment.

Uses of Solvency Ratios by Creditors and Investors

Creditors, such as banks and bondholders, heavily rely on solvency ratios to assess the creditworthiness of borrowers. Low solvency ratios may indicate a higher risk of default, leading to higher interest rates or a refusal to extend credit. For example, a bank considering a loan application will examine a company’s debt-to-equity ratio and times interest earned ratio to determine the likelihood of loan repayment. Investors, on the other hand, use solvency ratios to evaluate the financial risk associated with investing in a company. High levels of debt can indicate a higher risk of financial distress, potentially impacting the value of their investment. A company with strong solvency ratios is generally perceived as a less risky investment.

Debt-to-Equity Ratio vs. Times Interest Earned Ratio

The debt-to-equity ratio and the times interest earned ratio are two commonly used solvency ratios, each offering a different perspective on a company’s financial leverage and ability to service its debt. While both are crucial for assessing solvency, they provide distinct insights.

| Feature | Debt-to-Equity Ratio | Times Interest Earned Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Measures the proportion of a company’s financing that comes from debt relative to equity. Calculated as Total Debt / Total Equity. | Measures a company’s ability to meet its interest payments on debt. Calculated as Earnings Before Interest and Taxes (EBIT) / Interest Expense. |

| Focus | Capital structure and financial leverage. | Ability to pay interest expenses. |

| Interpretation | A higher ratio indicates greater reliance on debt financing, implying higher financial risk. | A higher ratio indicates greater ability to cover interest payments, suggesting lower financial risk. |

| Example | A debt-to-equity ratio of 2.0 suggests that a company has twice as much debt as equity. | A times interest earned ratio of 5.0 indicates that a company’s EBIT is five times its interest expense. |

Profitability Ratios

Profitability ratios are crucial financial metrics that assess a company’s ability to generate earnings from its operations. They provide insights into how effectively a company manages its resources to produce profits, and are essential for evaluating the overall financial health and performance of a business. These ratios are used by investors, creditors, and management to gauge the efficiency and effectiveness of a company’s operations.

Gross Profit Margin

The gross profit margin reveals the profitability of a company’s core business operations after accounting for the direct costs of producing goods or services. It shows the percentage of revenue remaining after deducting the cost of goods sold (COGS). A higher gross profit margin generally indicates greater efficiency in production and pricing strategies.

The calculation involves subtracting the cost of goods sold from revenue, then dividing the result by revenue. The formula is:

Gross Profit Margin = (Revenue – Cost of Goods Sold) / Revenue

For example, if a company has revenue of $1,000,000 and a cost of goods sold of $600,000, its gross profit margin is ($1,000,000 – $600,000) / $1,000,000 = 0.4 or 40%. An increase in sales revenue with COGS remaining constant will increase the gross profit margin. Conversely, an increase in COGS with revenue remaining constant will decrease the gross profit margin.

Operating Profit Margin

The operating profit margin provides a more comprehensive view of profitability by considering both direct and indirect costs associated with running the business. It measures the percentage of revenue remaining after deducting all operating expenses, including COGS, selling, general, and administrative expenses. A higher operating profit margin suggests better management of operational costs and overall business efficiency.

The calculation involves dividing operating profit (revenue minus all operating expenses) by revenue. The formula is:

Operating Profit Margin = Operating Profit / Revenue

For example, if a company has revenue of $1,000,000 and operating expenses (including COGS) totaling $700,000, its operating profit is $300,000, and its operating profit margin is $300,000 / $1,000,000 = 0.3 or 30%. Increases in revenue while holding operating expenses constant will increase the operating profit margin. Conversely, increases in operating expenses while holding revenue constant will decrease the operating profit margin.

Net Profit Margin

The net profit margin is the ultimate measure of profitability, representing the percentage of revenue remaining after all expenses, including interest, taxes, and other non-operating expenses, have been deducted. It shows the company’s overall efficiency in generating profits from its operations and financial activities. A higher net profit margin indicates superior financial performance and efficiency.

The calculation involves dividing net profit (revenue minus all expenses) by revenue. The formula is:

Net Profit Margin = Net Profit / Revenue

For example, if a company has revenue of $1,000,000 and net profit of $150,000, its net profit margin is $150,000 / $1,000,000 = 0.15 or 15%.

The effects of changes in sales revenue and expenses on these ratios can be summarized as follows:

The following table illustrates how changes in sales revenue and expenses affect profitability ratios:

| Scenario | Effect on Gross Profit Margin | Effect on Operating Profit Margin | Effect on Net Profit Margin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Increase in Sales Revenue, COGS constant | Increases | Increases | Increases |

| Increase in COGS, Sales Revenue constant | Decreases | Decreases | Decreases |

| Increase in Operating Expenses, Sales Revenue constant | No Change | Decreases | Decreases |

| Decrease in Operating Expenses, Sales Revenue constant | No Change | Increases | Increases |

| Increase in Interest Expense, other factors constant | No Change | No Change | Decreases |

| Decrease in Taxes, other factors constant | No Change | No Change | Increases |

Efficiency Ratios

Efficiency ratios are crucial indicators of a company’s operational effectiveness. They reveal how well a business manages its assets and liabilities to generate sales and profits. Unlike liquidity or solvency ratios that focus on short-term survival or long-term stability, efficiency ratios provide insights into the effectiveness of resource utilization. Analyzing these ratios allows businesses to identify areas for improvement in their operational processes and ultimately enhance profitability.

Inventory Turnover Ratio

The inventory turnover ratio measures how efficiently a company manages its inventory. A higher ratio generally suggests efficient inventory management, minimizing storage costs and the risk of obsolescence. Conversely, a low ratio might indicate overstocking, slow-moving inventory, or potential issues with demand forecasting. The formula for calculating this ratio is:

Cost of Goods Sold / Average Inventory

The average inventory is typically calculated as the average of the beginning and ending inventory for a given period. For example, a company with a cost of goods sold of $500,000 and an average inventory of $100,000 has an inventory turnover ratio of 5. This means the company sells and replaces its inventory five times a year.

Accounts Receivable Turnover Ratio

The accounts receivable turnover ratio assesses how effectively a company collects payments from its customers. A high ratio indicates efficient credit and collection policies, minimizing the time money is tied up in outstanding invoices. A low ratio may suggest lenient credit terms, poor collection practices, or difficulties in managing customer accounts. The calculation is:

Net Credit Sales / Average Accounts Receivable

For instance, if a company has net credit sales of $800,000 and an average accounts receivable of $100,000, its accounts receivable turnover ratio is 8. This implies that the company collects its receivables eight times a year.

Accounts Payable Turnover Ratio

The accounts payable turnover ratio indicates how efficiently a company manages its payments to suppliers. A lower ratio (within reasonable limits) might suggest effective negotiation of credit terms, maximizing available cash flow. A high ratio, however, could signal potential problems with paying suppliers on time, potentially damaging supplier relationships and creditworthiness. The formula is:

Cost of Goods Sold / Average Accounts Payable

Consider a company with a cost of goods sold of $500,000 and an average accounts payable of $50,000. Its accounts payable turnover ratio is 10, suggesting the company pays its suppliers ten times a year.

Case Study: Comparing Two Retail Companies

Let’s compare two hypothetical retail companies, “Retail A” and “Retail B,” using efficiency ratios. Both companies have similar sales revenue.

| Ratio | Retail A | Retail B |

|————————–|———-|———-|

| Inventory Turnover | 6 | 3 |

| Accounts Receivable Turnover | 9 | 6 |

| Accounts Payable Turnover | 8 | 12 |

Retail A demonstrates superior efficiency in managing inventory and receivables compared to Retail B. Its higher inventory turnover suggests better demand forecasting and reduced storage costs. The higher accounts receivable turnover indicates more efficient collection practices. However, Retail B’s higher accounts payable turnover might signal a need to review its payment terms with suppliers, ensuring positive supplier relationships aren’t jeopardized. This comparative analysis highlights the importance of using efficiency ratios to identify areas of strength and weakness in a company’s operations.

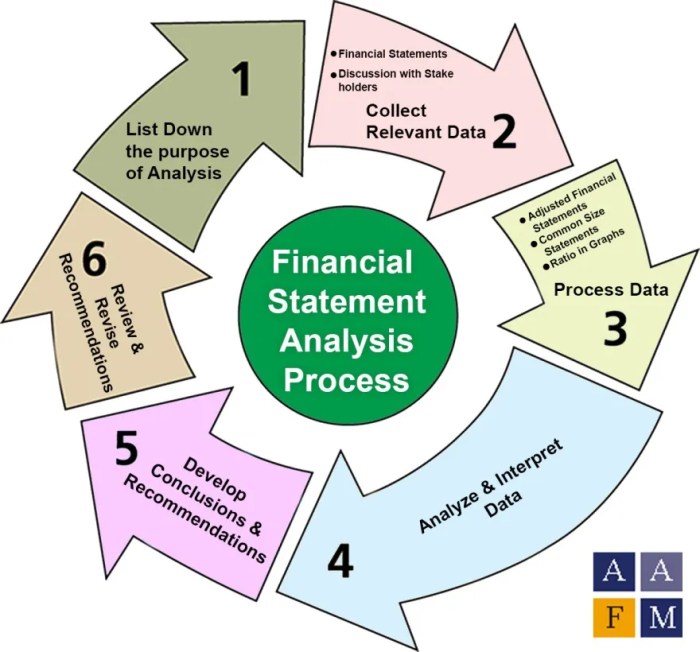

Interpreting Ratio Analysis Results

Ratio analysis provides valuable insights into a company’s financial health, but interpreting the results requires careful consideration and a nuanced understanding of the context. Simply calculating ratios without further analysis can lead to misleading conclusions. A comprehensive interpretation involves comparing ratios over time, benchmarking against industry peers, and incorporating qualitative factors.

Interpreting ratio analysis results effectively is crucial for making informed business decisions. Misinterpretations can lead to flawed strategies and potentially harmful consequences. Therefore, a thorough and multifaceted approach is essential.

Limitations of Isolated Ratio Analysis

Relying solely on ratio analysis without considering other factors can be deceptive. Individual ratios, taken in isolation, may not present a complete picture of a company’s financial standing. For example, a high current ratio might suggest strong liquidity, but if a significant portion of current assets consists of obsolete inventory, the true liquidity position could be weaker than initially perceived. Similarly, a high profit margin might seem positive, but if the company achieved this through aggressive cost-cutting that compromised product quality or customer service, long-term sustainability might be jeopardized. Therefore, a holistic approach that integrates various financial statements and qualitative information is necessary for a reliable assessment.

The Importance of Industry Benchmarks and Trends

Comparing a company’s ratios to industry averages and historical trends provides valuable context. Industry benchmarks offer a relative perspective, allowing for the assessment of a company’s performance compared to its peers. For instance, a low inventory turnover ratio might be acceptable in an industry with high-value, slow-moving goods but unacceptable in an industry characterized by fast-moving consumer goods. Analyzing trends over time reveals whether a company’s ratios are improving, deteriorating, or remaining stable, providing insights into the effectiveness of its strategies and operational efficiency. Reliable industry data can be obtained from sources like IBISWorld, Statista, and industry-specific publications.

Qualitative Factors Influencing Ratio Interpretation

Qualitative factors, which are non-numerical aspects of a business, can significantly impact the interpretation of ratio analysis. For example, a company with a high debt-to-equity ratio might appear financially risky, but if it has a strong track record of profitability and cash flow, the risk might be mitigated. Similarly, a low return on equity could be due to factors like a conservative investment strategy, rather than poor management. Other qualitative factors to consider include management quality, competitive landscape, technological advancements, regulatory changes, and macroeconomic conditions. A thorough analysis should consider both the quantitative data from ratio analysis and the qualitative context to provide a comprehensive evaluation of a company’s financial health and future prospects. For example, a company operating in a rapidly growing market might justify higher levels of debt than a company in a mature, stagnant market.

Visual Representation of Ratio Analysis

Visual representations are crucial for effectively communicating the insights derived from ratio analysis. Charts and graphs transform complex numerical data into easily digestible formats, highlighting trends and relationships that might be missed when reviewing raw numbers alone. This allows for a more intuitive understanding of a company’s financial health and performance over time and in comparison to other metrics.

Trend Analysis of Return on Equity (ROE)

A line graph is an excellent tool for visualizing the trend of a key ratio like Return on Equity (ROE) over several years. The horizontal axis would represent the time period (e.g., years 2018-2023), and the vertical axis would represent the ROE percentage. Each data point on the graph would represent the company’s ROE for a specific year. A line would connect these data points, illustrating the trend. For example, if a company’s ROE increased steadily from 10% in 2018 to 18% in 2023, the line would show an upward trend, indicating improved profitability and efficiency in utilizing shareholder equity. Conversely, a downward trend would signal potential concerns. The graph’s title could be “Return on Equity Trend (2018-2023),” and a clear legend should be included. The interpretation of the graph would focus on the overall direction of the line (upward, downward, or flat), identifying any significant changes in slope, and relating these changes to potential internal or external factors affecting the company’s performance.

Relationship between Profit Margin and Inventory Turnover

A scatter plot can effectively illustrate the relationship between two ratios, such as profit margin and inventory turnover. The horizontal axis would represent the inventory turnover ratio, and the vertical axis would represent the profit margin. Each data point would represent a specific year’s data, plotting the company’s inventory turnover against its profit margin for that year. A trend line could be added to the scatter plot to show the general relationship between the two ratios. For instance, a positive correlation would suggest that as inventory turnover increases (meaning the company is selling inventory more efficiently), profit margin also tends to increase. This could indicate efficient inventory management contributes to higher profitability. Conversely, a negative or weak correlation might suggest other factors are more influential on profitability than inventory turnover. The graph title might be “Profit Margin vs. Inventory Turnover,” and the axes should be clearly labeled with units. The interpretation would focus on the direction and strength of the correlation, and potential explanations for the observed relationship. For example, a strong positive correlation could support the implementation of strategies to improve inventory turnover as a means to boost profitability.

Ending Remarks

Mastering ratio analysis is a cornerstone of effective financial decision-making. By understanding the interplay between different ratio categories and interpreting results within the broader context of a company’s industry and overall economic climate, one can gain a deep understanding of its financial health. While limitations exist, the insights gleaned from ratio analysis are invaluable for investors, creditors, and management alike in evaluating risk, assessing performance, and guiding strategic planning. Remember, a comprehensive analysis considers not only the numbers but also the underlying qualitative factors that shape a company’s financial narrative.

Essential Questionnaire

What are the limitations of ratio analysis?

Ratio analysis relies on historical data and may not accurately predict future performance. It can be influenced by accounting practices and may not capture qualitative factors like management quality or industry-specific risks. Comparing ratios across companies requires careful consideration of differences in accounting methods and industry contexts.

How frequently should ratio analysis be performed?

The frequency depends on the specific needs and goals. For ongoing monitoring, quarterly or even monthly analysis might be appropriate. For strategic decision-making, annual reviews are often sufficient. The key is consistency in the approach and timeframe.

Can ratio analysis be used for all types of businesses?

While the fundamental principles apply broadly, the specific ratios and their interpretations may need adjustments based on the industry and business model. For example, ratios relevant to a manufacturing company may not be directly applicable to a service-based business.

What software can assist with ratio analysis?

Various spreadsheet software (like Microsoft Excel or Google Sheets) and dedicated financial analysis programs can greatly simplify the process. Many accounting software packages also include ratio analysis features.