Unlocking the secrets hidden within a company’s financial statements is the core of ratio analysis. This powerful technique allows us to assess a company’s financial health, operational efficiency, and profitability, providing crucial insights for investors, creditors, and management alike. By systematically examining key ratios, we can identify strengths, weaknesses, and potential risks, ultimately informing better decision-making.

This guide will explore various ratio analysis techniques, including liquidity, solvency, profitability, and activity ratios. We will delve into the calculation and interpretation of these ratios, examining their individual strengths and limitations, and demonstrating their practical application in diverse business scenarios. Understanding these techniques is essential for navigating the complex world of financial analysis and making informed judgments about a company’s future prospects.

Introduction to Ratio Analysis Techniques

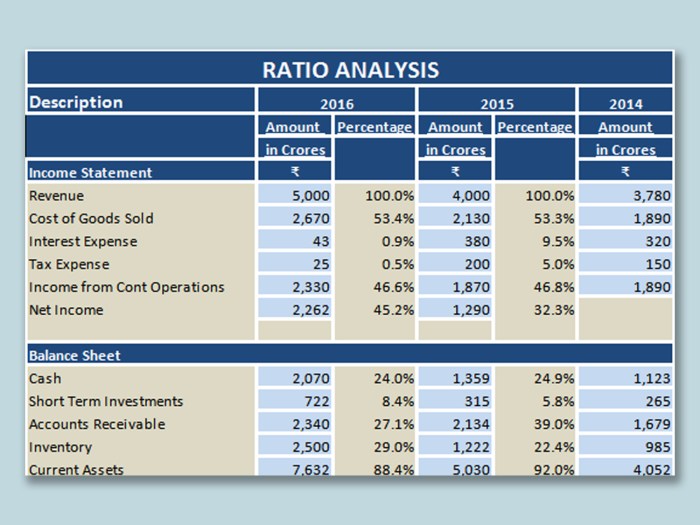

Ratio analysis is a powerful tool used in finance to evaluate the performance and financial health of a business. It involves calculating key ratios using data from a company’s financial statements—primarily the balance sheet and income statement—to gain insights into various aspects of its operations. The primary purpose of ratio analysis is to facilitate informed financial decision-making, whether that’s for internal management, potential investors, or lenders. By comparing ratios over time or against industry benchmarks, users can identify trends, strengths, weaknesses, and potential risks.

Understanding financial statements is crucial before performing ratio analysis. The accuracy and reliability of any ratio calculation are entirely dependent on the accuracy and completeness of the underlying financial data. Without a solid grasp of the balance sheet (showing assets, liabilities, and equity) and the income statement (showing revenues, expenses, and profits), the ratios derived will be meaningless and potentially misleading. A thorough understanding of accounting principles and the specific line items within these statements is essential for interpreting ratios correctly.

Different Types of Businesses Utilizing Ratio Analysis

Ratio analysis is a versatile technique applicable across a wide range of industries and business sizes. Large multinational corporations use sophisticated ratio analysis models to monitor performance across diverse business units. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) utilize simpler ratio analyses to track key performance indicators and make critical decisions regarding financing, expansion, or cost-cutting. Non-profit organizations also employ ratio analysis to assess their financial sustainability and demonstrate accountability to donors. For example, a retail chain might use ratio analysis to assess inventory turnover, while a manufacturing company might focus on analyzing its debt-to-equity ratio. A non-profit might analyze its fundraising efficiency ratio.

Types of Financial Ratios

Ratio analysis categorizes financial ratios into several key groups, each offering a different perspective on the company’s financial health. These categories are not mutually exclusive; often, a comprehensive analysis will utilize ratios from multiple categories.

| Ratio Type | Description | Example | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquidity Ratios | Measure a company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations. | Current Ratio (Current Assets / Current Liabilities) | A higher ratio indicates greater liquidity; however, an excessively high ratio may suggest inefficient asset management. |

| Solvency Ratios | Assess a company’s ability to meet its long-term obligations and its overall financial stability. | Debt-to-Equity Ratio (Total Debt / Total Equity) | A lower ratio indicates lower financial risk; a high ratio suggests a higher reliance on debt financing. |

| Profitability Ratios | Measure a company’s ability to generate profits from its operations. | Gross Profit Margin (Gross Profit / Revenue) | A higher margin indicates better profitability from sales; it shows efficiency in controlling the cost of goods sold. |

| Activity Ratios | Evaluate how efficiently a company manages its assets and liabilities. | Inventory Turnover (Cost of Goods Sold / Average Inventory) | A higher turnover suggests efficient inventory management; a low turnover may indicate slow-moving inventory or potential obsolescence. |

Liquidity Ratios

Liquidity ratios are crucial financial metrics that assess a company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations. They provide insights into a firm’s solvency and its capacity to convert assets into cash quickly. Understanding these ratios is vital for both internal management and external stakeholders like creditors and investors.

Current Ratio and Quick Ratio Calculations and Interpretations

The current ratio and the quick ratio are two fundamental liquidity ratios. The current ratio measures a company’s ability to pay off its current liabilities (due within one year) with its current assets (assets that can be converted into cash within one year). It’s calculated as:

Current Ratio = Current Assets / Current Liabilities

A higher current ratio generally suggests stronger liquidity. However, an excessively high ratio might indicate inefficient use of assets. A healthy current ratio is typically considered to be between 1.5 and 2.0, although this can vary depending on the industry.

The quick ratio, also known as the acid-test ratio, is a more conservative measure of liquidity. It excludes inventories from current assets, as inventory may not be easily or quickly converted to cash. The calculation is:

Quick Ratio = (Current Assets – Inventories) / Current Liabilities

A quick ratio is considered more stringent than the current ratio because it focuses solely on the most liquid assets. A healthy quick ratio is generally considered to be above 1.0.

Comparison of Current Ratio and Quick Ratio

The current ratio and quick ratio offer different perspectives on a company’s short-term liquidity. The current ratio provides a broader picture, encompassing all current assets. Its strength lies in its simplicity and comprehensiveness. However, its weakness is that it includes inventories, which might not be readily convertible to cash, potentially overstating liquidity.

The quick ratio, on the other hand, offers a more conservative assessment by excluding inventories. Its strength lies in its focus on highly liquid assets, providing a more realistic view of immediate payment capabilities. Its weakness is that it might underestimate a company’s overall liquidity if the company has a high inventory turnover rate and can readily convert inventory into cash.

Examples of Low Current Ratio Indicating Financial Problems

A low current ratio, below 1.0, signals that a company may struggle to meet its short-term obligations. For example, a retail company with a current ratio of 0.8 might find itself unable to pay its suppliers on time, potentially leading to disruptions in its supply chain. Similarly, a manufacturing company with a low current ratio might face difficulties in meeting payroll or paying off short-term loans, potentially leading to financial distress. These scenarios highlight the importance of maintaining a healthy current ratio.

Hypothetical Scenario: Impact of Inventory Changes on Liquidity Ratios

Let’s consider a hypothetical scenario involving “XYZ Corp,” a clothing retailer. Initially, XYZ Corp has current assets of $100,000 (including inventory of $40,000) and current liabilities of $50,000. Its current ratio is 2.0 ($100,000/$50,000) and its quick ratio is 1.2 (($100,000-$40,000)/$50,000).

Now, suppose XYZ Corp experiences a significant increase in inventory due to overstocking, raising its inventory to $70,000, while current liabilities remain at $50,000. Current assets are now $130,000. The current ratio increases to 2.6 ($130,000/$50,000), seemingly suggesting improved liquidity. However, the quick ratio falls to 1.2 (($130,000 – $70,000)/$50,000), indicating a decrease in readily available cash to meet short-term obligations. This illustrates how changes in inventory can significantly impact the interpretation of liquidity ratios, highlighting the importance of considering both ratios for a complete picture.

Solvency Ratios

Solvency ratios are crucial indicators of a company’s ability to meet its long-term financial obligations. Unlike liquidity ratios, which focus on short-term obligations, solvency ratios assess a company’s capacity to survive and thrive over an extended period. A strong solvency position suggests a lower risk of bankruptcy or financial distress. Conversely, weak solvency ratios can signal potential problems. Two key ratios provide valuable insights into a company’s long-term financial health: the debt-to-equity ratio and the times interest earned ratio.

These ratios offer a comprehensive picture of a company’s financial leverage and its capacity to manage its debt burden. Analyzing these ratios in conjunction with other financial metrics provides a holistic view of a company’s financial stability and risk profile. Understanding these ratios is vital for investors, creditors, and management in making informed decisions.

Debt-to-Equity Ratio

The debt-to-equity ratio measures the proportion of a company’s financing that comes from debt relative to equity. It indicates the extent to which a company relies on borrowed funds versus owner’s investment. A higher ratio suggests a greater reliance on debt financing, which can amplify both profits and losses. This ratio is a significant indicator of financial risk.

- Formula:

Total Debt / Total Equity

- Interpretation: A ratio of 1.0 indicates that a company has equal amounts of debt and equity financing. A ratio greater than 1.0 suggests a higher proportion of debt financing, potentially increasing financial risk. A lower ratio implies a greater reliance on equity financing, generally considered less risky.

- Example: If a company has total debt of $50 million and total equity of $25 million, its debt-to-equity ratio is 2.0 (50/25). This indicates that the company is using twice as much debt financing as equity financing.

Times Interest Earned Ratio

The times interest earned (TIE) ratio, also known as the interest coverage ratio, assesses a company’s ability to meet its interest obligations using its earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT). It provides a measure of the company’s safety margin in paying its interest expenses. A higher TIE ratio indicates greater financial strength and a lower risk of default on interest payments.

- Formula:

Earnings Before Interest and Taxes (EBIT) / Interest Expense

- Interpretation: A TIE ratio of 2.0 indicates that a company’s EBIT is twice its interest expense. This implies a comfortable cushion to cover interest payments. A lower ratio suggests a greater difficulty in meeting interest obligations, increasing the risk of default.

- Example: If a company has EBIT of $10 million and interest expense of $2 million, its TIE ratio is 5.0 (10/2). This suggests a strong ability to meet its interest obligations.

Risks Associated with High Debt Levels

High debt levels, as indicated by elevated debt-to-equity and low TIE ratios, expose companies to several significant risks. These risks can negatively impact long-term financial stability and potentially lead to financial distress or bankruptcy.

- Increased Financial Risk: High debt increases the vulnerability to economic downturns. Reduced revenues can make it difficult to meet debt obligations, potentially leading to default.

- Higher Interest Expense: Significant debt burdens translate into substantial interest payments, reducing profitability and potentially limiting investment in growth opportunities.

- Limited Financial Flexibility: High debt can constrain a company’s ability to borrow additional funds for necessary investments or to weather unexpected events.

- Increased Risk of Bankruptcy: If a company fails to meet its debt obligations, it faces the risk of bankruptcy, potentially leading to liquidation or restructuring.

Profitability Ratios

Profitability ratios are crucial indicators of a company’s ability to generate earnings from its operations. They reveal how effectively a company is managing its resources to produce profits. Analyzing these ratios provides valuable insights into a company’s efficiency, pricing strategies, and overall financial health. By examining various profit margins, investors and analysts can assess the company’s performance relative to its competitors and industry benchmarks.

Gross Profit Margin

The gross profit margin measures the profitability of a company’s core business operations after accounting for the direct costs of producing goods or services. It shows the percentage of revenue remaining after deducting the cost of goods sold (COGS). A higher gross profit margin generally indicates greater efficiency in production or a stronger pricing strategy. Changes in sales revenue directly impact the gross profit margin; an increase in sales revenue, holding COGS constant, will increase the margin, while a decrease in sales revenue will decrease the margin. Similarly, changes in COGS, holding sales revenue constant, will inversely affect the gross profit margin. A decrease in COGS increases the margin, while an increase in COGS decreases the margin.

Operating Profit Margin

The operating profit margin, also known as the return on sales, goes beyond gross profit to incorporate operating expenses. It reflects the profitability of a company’s operations after considering both the cost of goods sold and operating expenses, such as salaries, rent, and utilities. This ratio provides a clearer picture of a company’s operational efficiency, as it accounts for a wider range of costs associated with running the business. Increases in sales revenue, with operating expenses remaining constant, will lead to a higher operating profit margin. Conversely, increases in operating expenses, with sales revenue remaining constant, will decrease the operating profit margin.

Net Profit Margin

The net profit margin represents the ultimate profitability of a company after all expenses, including interest, taxes, and other non-operating expenses, have been deducted from revenue. This is the “bottom line” profitability, showing the percentage of revenue that translates into actual profit for the company’s shareholders. It provides a comprehensive overview of the company’s overall financial performance. An increase in sales revenue, holding all expenses constant, results in a higher net profit margin. Conversely, an increase in any expense category, while sales revenue remains constant, reduces the net profit margin.

Comparison of Profitability Ratios

The three profitability ratios—gross profit margin, operating profit margin, and net profit margin—provide a layered view of a company’s profitability. The gross profit margin focuses solely on the direct costs of production, while the operating profit margin incorporates operating expenses, offering a broader perspective. The net profit margin considers all expenses, providing the most comprehensive picture of overall profitability. By analyzing all three, analysts gain a complete understanding of where a company’s profits are generated and what factors influence its overall profitability.

| Ratio | Formula | Interpretation | Impact of Changes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gross Profit Margin | (Revenue – Cost of Goods Sold) / Revenue | Percentage of revenue remaining after deducting direct costs of production. | Increased by higher revenue or lower COGS; decreased by lower revenue or higher COGS. |

| Operating Profit Margin | Operating Income / Revenue | Percentage of revenue remaining after deducting both cost of goods sold and operating expenses. | Increased by higher revenue or lower operating expenses; decreased by lower revenue or higher operating expenses. |

| Net Profit Margin | Net Income / Revenue | Percentage of revenue remaining after all expenses, including taxes and interest, are deducted. | Increased by higher revenue or lower expenses; decreased by lower revenue or higher expenses. |

Activity Ratios

Activity ratios provide insights into how efficiently a company manages its assets and liabilities to generate sales. They gauge the effectiveness of operational processes, revealing areas for potential improvement in resource utilization and overall performance. A strong understanding of these ratios is crucial for assessing a company’s operational health and identifying areas for enhanced efficiency.

Inventory Turnover Ratio

The inventory turnover ratio measures how efficiently a company manages its inventory. It indicates the number of times inventory is sold and replaced over a specific period, typically a year. A higher ratio generally suggests efficient inventory management, while a lower ratio might indicate overstocking, obsolete inventory, or weak sales. The formula for calculating the inventory turnover ratio is:

Cost of Goods Sold / Average Inventory

Average inventory is calculated by summing the beginning and ending inventory values and dividing by two. For example, if a company has a cost of goods sold of $1,000,000 and an average inventory of $200,000, its inventory turnover ratio is 5 ($1,000,000 / $200,000). This signifies that the company sold and replaced its entire inventory five times during the period. A low turnover ratio could indicate a need for better forecasting, improved sales strategies, or more efficient inventory control systems.

Accounts Receivable Turnover Ratio

The accounts receivable turnover ratio assesses how efficiently a company collects payments from its customers. It shows how many times, on average, accounts receivable are collected during a period. A higher ratio indicates efficient credit and collection policies, while a lower ratio may suggest problems with credit risk management or slow collection processes. The formula is:

Net Credit Sales / Average Accounts Receivable

Average accounts receivable is calculated similarly to average inventory. For instance, if a company has net credit sales of $800,000 and average accounts receivable of $100,000, its accounts receivable turnover ratio is 8 ($800,000 / $100,000). This implies that the company collected its outstanding receivables eight times during the period. A low ratio might necessitate a review of credit policies, stricter collection procedures, or improved customer communication.

Days Sales Outstanding

Days Sales Outstanding (DSO), also known as Days Sales in Receivables, indicates the average number of days it takes a company to collect payment after a sale. A lower DSO is generally preferred, signifying efficient collection practices. A high DSO suggests potential issues with credit risk management or slow collection processes, potentially leading to cash flow problems. The formula is:

(Average Accounts Receivable / Net Credit Sales) * Number of Days in the Period

Using the previous example, with average accounts receivable of $100,000 and net credit sales of $800,000 over a 365-day period, the DSO would be 45.6 days (($100,000 / $800,000) * 365). This suggests that, on average, it takes the company 45.6 days to collect payment. A prolonged DSO could warrant a review of credit terms, customer segmentation for risk assessment, and improved collection strategies.

Impact of Improved Inventory Management on Activity Ratios

Improving inventory management can significantly impact activity ratios. Consider a hypothetical case study of a retail company facing slow inventory turnover. Initially, the company had an inventory turnover ratio of 2 and a DSO of 60 days. By implementing a Just-In-Time (JIT) inventory system and improving forecasting accuracy, the company reduced its average inventory while maintaining sales. This resulted in an increased inventory turnover ratio to 4 and a decreased DSO to 45 days. The improved efficiency translated to reduced storage costs, lower obsolescence risk, and faster cash flow, directly impacting profitability and overall financial health. The reduction in DSO further indicates improved efficiency in collecting payments from customers. This demonstrates how strategic inventory management directly enhances activity ratios, reflecting improved operational efficiency.

Limitations of Ratio Analysis

Ratio analysis, while a powerful tool for evaluating a company’s financial health, is not without its limitations. Over-reliance on ratios alone can lead to inaccurate or incomplete assessments, potentially resulting in flawed financial decisions. A comprehensive understanding of these limitations is crucial for effective financial analysis.

While ratios provide a quantitative snapshot of a company’s performance, they lack the depth and nuance provided by qualitative factors. These factors, which are often difficult to quantify, can significantly impact a company’s future prospects. Ignoring them can lead to a skewed interpretation of the financial data.

Influence of Accounting Methods

Different accounting methods can significantly affect the calculated ratios. For instance, the choice between FIFO (First-In, First-Out) and LIFO (Last-In, First-Out) inventory costing methods can impact the cost of goods sold and, consequently, the gross profit margin. Similarly, the depreciation method chosen can affect the reported net income and asset values, influencing profitability and solvency ratios. A comparison of companies using different accounting methods requires careful adjustment and consideration to ensure a fair assessment. For example, a company using accelerated depreciation will show lower net income and assets compared to a company using straight-line depreciation, affecting ratios like return on assets.

Industry Variations and Comparability

Direct comparison of ratios across different industries can be misleading. Industries operate under different economic conditions, regulatory environments, and competitive landscapes. A high debt-to-equity ratio might be perfectly acceptable in a capital-intensive industry like manufacturing, but alarming in a service-oriented business. Therefore, meaningful comparisons should be restricted to companies within the same industry and with similar business models. For example, comparing the profitability ratios of a technology startup with those of a mature utility company would be unproductive due to fundamental differences in their business models and risk profiles.

Qualitative Factors

The limitations of relying solely on quantitative data necessitate the incorporation of qualitative factors. These include management quality, employee morale, brand reputation, technological advancements, and the overall economic climate. For example, a company with strong financial ratios might still face significant challenges if its management team lacks experience or if its brand reputation is tarnished. Conversely, a company with seemingly weak ratios might have strong potential if it benefits from innovative technology or enjoys a strong market position. A balanced approach that considers both quantitative and qualitative factors provides a more comprehensive and accurate assessment.

Using Ratio Analysis for Specific Business Decisions

Ratio analysis is a powerful tool extending beyond simple financial health checks. It provides crucial insights for informed decision-making across various business functions, from assessing creditworthiness to guiding strategic resource allocation. By analyzing the relationships between different financial statement items, businesses can gain a deeper understanding of their performance and make data-driven choices.

Ratio analysis offers a structured approach to evaluating a company’s financial standing, enabling stakeholders to make informed decisions based on objective metrics rather than gut feeling. This structured approach allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the business’s financial health and potential risks and opportunities.

Credit Risk Assessment Using Ratio Analysis

Credit risk assessment relies heavily on ratio analysis to determine a borrower’s ability to repay debt. Lenders use various ratios to gauge a company’s liquidity, solvency, and profitability, thus mitigating the risk of default. For example, a high debt-to-equity ratio might indicate a high level of financial leverage and increased risk, while a low current ratio might signal potential liquidity problems. Credit scoring models often incorporate multiple ratios to create a comprehensive risk profile. A low quick ratio (acid-test ratio), which excludes inventories from current assets, might further signal a higher risk of default, as it indicates the company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations using only its most liquid assets.

Ratio Analysis and Investment Decisions

Investors utilize ratio analysis to evaluate the financial performance and potential of companies before making investment decisions. Profitability ratios, such as return on assets (ROA) and return on equity (ROE), indicate how efficiently a company is generating profits. Growth ratios, such as the earnings per share (EPS) growth rate, offer insights into a company’s past performance and potential future growth. By comparing a company’s ratios to industry benchmarks and its historical performance, investors can assess its relative attractiveness and potential for future returns. For example, a consistently high ROA compared to competitors suggests strong management and operational efficiency, making it a potentially attractive investment.

Ratio Analysis in Strategic Planning and Resource Allocation

Strategic planning and resource allocation benefit significantly from ratio analysis. By analyzing activity ratios, such as inventory turnover and accounts receivable turnover, businesses can identify areas for improvement in operational efficiency. For example, a low inventory turnover ratio might indicate excessive inventory levels, tying up capital and potentially leading to obsolescence. Understanding these inefficiencies allows for better resource allocation, such as optimizing inventory management or improving collection procedures. This analysis facilitates better decision-making regarding investment in new equipment, expansion plans, or process improvements.

Stakeholder Use of Ratio Analysis

Different stakeholders utilize ratio analysis in distinct ways. Investors focus on profitability and growth ratios to assess investment potential and risk. Creditors concentrate on liquidity and solvency ratios to evaluate the borrower’s creditworthiness and ability to repay loans. Managers use a comprehensive set of ratios to monitor operational efficiency, identify areas for improvement, and track progress towards strategic goals. For instance, a manager might use the debt-to-equity ratio to monitor the company’s financial leverage and make informed decisions about capital structure. Analyzing the inventory turnover ratio helps managers optimize inventory levels and reduce storage costs.

Last Word

Mastering ratio analysis empowers individuals to interpret financial statements with greater accuracy and confidence. By understanding the nuances of liquidity, solvency, profitability, and activity ratios, one can effectively assess a company’s financial health and make informed decisions. Remember, while ratios provide valuable quantitative insights, they should be considered alongside qualitative factors for a comprehensive understanding of a company’s overall performance and potential. The ability to critically analyze financial data is a valuable skill applicable across numerous business contexts.

Detailed FAQs

What are the ethical considerations when using ratio analysis?

It’s crucial to use accurate and up-to-date financial data. Misrepresenting data or selectively choosing ratios to support a predetermined conclusion is unethical and can have serious consequences.

How can I compare ratios across different companies in varying industries?

Direct comparisons are challenging due to industry-specific differences. Benchmarking against industry averages or similar-sized companies within the same sector provides a more meaningful comparison.

How often should ratio analysis be performed?

The frequency depends on the specific needs and context. Regular monitoring, such as quarterly or annually, is generally recommended for effective financial tracking and decision-making.

What software can assist with ratio analysis?

Spreadsheet software like Microsoft Excel or Google Sheets, and dedicated financial analysis software packages can significantly simplify the calculations and visualization of ratio analysis.